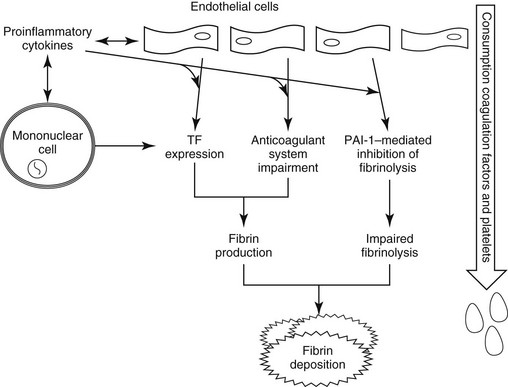

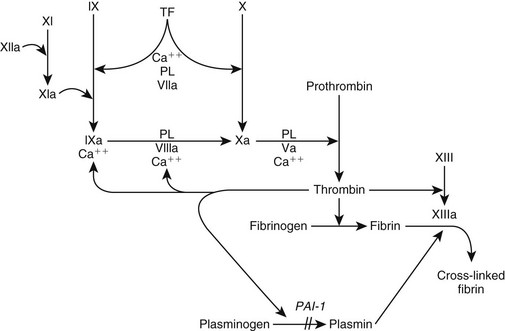

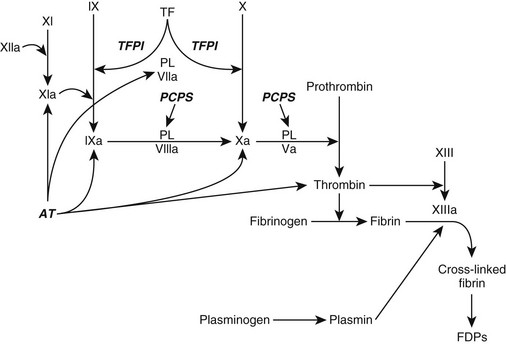

Chapter 63 The pathogenesis of DIC is characterized by (1) increased thrombin production, (2) suppression of physiologic anticoagulant pathways, (3) impaired fibrinolysis, and (4) activation of inflammatory pathways (Figure 63-1). Tissue factor (TF) is expressed on monocytes and endothelial cells within the circulation during inflammation and on malignant cells in cancer patients. The TF : factor VIIa complex (extrinsic pathway), the main stimulus for thrombin formation in DIC, activates factor IX (intrinsic pathway) and factor X (common pathway) (Figure 63-2). In human cancer patients DIC also can involve the expression of a specific cancer procoagulant, a cysteine protease that has factor X–activating properties. Figure 63-1 Alterations in coagulation and anticoagulation during systemic inflammation and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Fibrin deposition exceeds fibrinolysis when tissue factor (TF) expression is enhanced, the anticoagulation system is impaired, and levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) are increased. Figure 63-2 Coagulation during inflammation promoting thrombin and fibrin production. Tissue factor (TF) is the prime initiator of coagulation. Amplification of the coagulation scheme during disseminated intravascular coagulation occurs by activation of factor IX (cross talk) and continued activation of factors VIII and IX and platelet surfaces by thrombin (feedback). Plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) prevents plasmin activation and fibrinolysis. During inflammation there is inhibition of fibrinolysis when PAI-1 is up-regulated and promotion of fibrin deposition. Ca++, Calcium; PL, phospholipase. Impaired function of the normal physiologic anticoagulant pathways (see Figures 63-2 and 63-3) during DIC allows thrombin generation and the resultant fibrin formation to become exaggerated. Antithrombin (AT), a natural anticoagulant, binds to thrombin and inactivates thrombin and factors IXa, Xa, XIa, and TF : factor VIIa. During DIC, AT levels are reduced as a result of increased AT consumption by AT-thrombin complex formation, AT degradation by neutrophil elastase, impaired hepatic synthesis of AT, and loss of AT because of increased capillary permeability. Depression of endogenous anticoagulant protein C : protein S activity results from enhanced consumption, impaired hepatic synthesis, and capillary leakage. In addition, proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α] and interleukin-1β [IL-1β]) can cause down-regulation of protein C–thrombomodulin expression on endothelial cell surfaces. Figure 63-3 Anticoagulation process, which normally should balance coagulation. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) is a protease inhibitor of tissue factor (TF) complex. Bound to thrombin, antithrombin (AT) inactivates thrombin and factors IXa, Xa, XIa, and TF : factor VIIa. The protein C : protein S (PCPS) system irreversibly inactivates factors Va and VIIIa. Activation of plasminogen produces plasmin, which lyses fibrin and fibrinogen into fibrin degradation products (FDPs) and fibrin monomers. During inflammation there is consumption and inhibition of the anticoagulants and promotion of fibrin deposition. PL, Phospholipase. The “cross talk” between the coagulation system and the inflammatory reaction is an important factor contributing to DIC pathogenesis (see Figure 63-1). Activated coagulation proteins stimulate the endothelial cells to release inflammatory cytokines. Recruited white blood cells release TNF-α (activating factor VII), IL-1, and IL-6 (activating factors VII and XII). Platelet-activating factor, a strong promoter of platelet aggregation, also is released from inflammatory cells. Additional activation of the inflammatory cascade is promoted by thrombin and other serine proteases interacting with protease-activated receptors on cell surfaces. The typical antiinflammatory effect of activated protein C is lost with depression of the protein C system during DIC, which enhances the proinflammatory state of DIC. DIC should be an anticipated complication in any animal experiencing one or more of the following: hypotensive crisis, impaired blood flow to a major organ, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or release of vasoactive agents into the vasculature (Box 63-1). The severity of clinical signs associated with DIC can range from no signs to life-threatening complications of vascular microthrombosis reflected by organ dysfunction or evidence of systemic bleeding. Clinical signs can vary as DIC progresses.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

Pathogenesis

Clinical Findings

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation