• Diagnosis is made by direct observation of a small globe. The third eyelid normally protrudes, which may obscure the globe. If the eye is very small, it may not be visible. • Treatment is not usually possible. If a cataract is the only abnormality found and the other reflexes are normal, the cataract could be surgically removed. • Very small globes may lead to chronic ocular discharge and entropion. In this situation, enucleation is recommended if there is no vision. Removing a globe from a young foal may lead to poor orbital development and therefore an orbital prosthesis might be considered. • Repeating the same sire/dam breeding should be avoided in Thoroughbreds. • Diagnosis is made by observing congenital abnormalities in an eye which can include a range of symptoms, such as corneal opacity due to stromal, Descemet’s membrane or corneal endothelium abnormalities, megalocornea, adhesions of the iris to other structures in the eye (the cornea or the anterior lens capsule), cataract, lens coloboma or microphakia. • Treatment is not usually possible. If a cataract is present but the cornea is clear and the other reflexes are normal, the cataract could be surgically removed. • Diagnosis is made by combining the history of ocular trauma or inflammation with the appearance of a shrunken globe, usually with a vascularized and fibrosed cornea. The eye should be assessed for discomfort, observing blepharospasm or ocular discomfort. The eyelids should be assessed for entropion. • If the eye appears uncomfortable, it should be enucleated and the orbit should be closed. • Diagnosis is usually made on the characteristic clinical appearance. However, if the diagnosis is not clear from the clinical appearance alone, a fine-needle aspirate or biopsy would confirm the presence of fat. • Differential diagnosis: nictitans gland cyst, inflammation, granuloma and neoplasia. • In most instances, this is a cosmetic condition that does not cause any problem to the affected horse. • Occasionally it leads to epiphora and the herniation may be extensive. In the latter cases, it may be surgically resected subconjunctivally, along with suturing the conjunctiva to prevent recurrence. The prognosis is very good. • Signs that may be noticed include exophthalmos (forward displacement of the globe due to a retrobulbar space-occupying lesion), prominent third eyelid, deviation of gaze (strabismus), asymmetry of the eyelash angle and distension of the supraorbital fossa. • The affected globe should be retropulsed, there is normally resistance to retropulsion but no pain (compared with a retrobulbar abscess, which is painful), local lymph nodes should be examined and a neurological assessment performed. • Orbital ultrasound might be useful in order to take a guided biopsy of the area. Ideally, further diagnostic imaging such as radiography, CT or MRI is undertaken. • This involves surgical removal of the neoplasm, if there is no evidence of metastasis. Surgical treatment may involve enucleation or exenteration (removal of eye, adnexa and part of bony orbit). • Chemotherapy or radiotherapy might be appropriate, depending on the type of tumor present. • Otherwise, palliative care might be provided if removal of the neoplasm is not an option. • In young foals this normally involves placing three to four temporary tacking vertical mattress sutures to evert the eyelid margin, relieving the anatomical and spastic components of the condition. Usually this allows sufficient time for the underlying problem, such as dehydration, to be rectified. • Topical lubricating ophthalmic ointment should be used during this time. A topical antibiotic should be used if the cornea is ulcerated. • If entropion persists despite several temporary tacking procedures, permanent surgical repair is required. The Hotz-Celsus procedure involves removing a section of adjacent eyelid skin, everting the affected eyelid. • Cicatricial entropion requires surgery to remove the scarred eyelid. Cilia disorders are uncommon in horses. Distichia are hairs that arise from meibomian gland orifices. These may contact the globe and result in frictional irritation, manifested as blepharospasm, ocular discharge and keratitis, occasionally becoming ulcerative. Ectopic cilia are cilia that arise from the palpebral conjunctiva and contact the globe. A cases series of seven cases has been published (Hurn et al. 2005), and ophthalmic examination revealed a single translucent cilium in the upper eyelid palpebral conjunctiva, emerging approximately 5 mm from the eyelid margin. Post-traumatic trichiasis might occur as a result of inappropriately healed eyelid trauma. • Application of topical ocular lubrication is sufficient if the irritation is mild. However, permanent destruction of the hair follicles is preferable, and this might be achieved with electrolysis or cryotherapy. • Treatment of ectopic cilia is with transconjunctival surgical excision. • Treatment of trichiasis as a result of eyelid scarring involves corrective blepharoplasty. Prognosis is very good with appropriate treatment. • Diagnosis is made by observing the absence of a distal nasolacrimal duct punctum in the nares. It is normally positioned on the floor of the nostril in the ventral nasal meatus. Fluorescein is applied to the lacrimal sac, and there is no passage of the dye to the nares because of the lack of normal drainage. • Contrast radiography may be used to locate the level of the obstruction, but it is most commonly present at the distal region. • Surgical recreation of a patent nasolacrimal system is required. This usually involves cannulating the nasolacrimal duct from the proximal aspect, through either the upper or lower nasolacrimal punctum. A No. 5 French urinary catheter or polyethylene tubing may be used. The catheter is advanced towards the nose and a quantity of fluid is instilled. • This usually causes a distension over the mucosa in the nares, and an incision can be made at this site, allowing advancement of the catheter. If no distension is seen, the tip of the catheter might be palpated at the expected site, and the incision made over this. The catheter or tubing is passed through the false nostril and sutured to the side of the face, and it is left in position for several weeks. • Diagnosis is usually obvious but the orbit should be carefully assessed for fractures by gently palpating the orbital rim. The conjunctiva and cornea should also be assessed for injury. If the wound is near the medial canthus, the nasolacrimal puncta and canaliculi should be carefully assessed for injury. • Differential diagnosis (of a chronic laceration): ulcerated mass such as squamous cell carcinoma or severe solar blepharitis. • Treatment involves prompt surgical repair. This can be achieved with topical and regional anesthesia, with sedation. The eyelid should be cleansed with a dilute disinfectant which is not harmful to the eye, such as 10% povidone iodine solution, at a 1 : 50 dilution. Minimal debridement is required, and hanging eyelid pedicles should be replaced rather than amputated. • Full-thickness laceration may require two-layer closure, and a deep conjunctival layer should first be gently apposed using a continuous pattern with an absorbable suture (for example 6-0 polyglactin 910). • The eyelid margin should be carefully re-aligned using a figure-of-eight suture. The external skin is then repaired with simple interrupted sutures. Poor realignment or second intention healing can result in incomplete eyelid closure which can lead to drying to the exposed cornea and subsequent ulceration. • The prognosis is normally very good with meticulous and timely surgical repair. • A complete ocular examination is indicated, along with the Jones test for fluorescein dye passage. Absence of fluorescein dye at the ipsilateral nares 5–10 minutes after application indicates an obstruction of normal tear drainage down the nasolacrimal duct. • If the discharge is purulent, an aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture and sensitivity test is indicated. • The adnexa and head should be examined for possible causes of nasolacrimal duct obstruction. • Contrast radiography might be employed to ascertain the location of the blockage. • Careful flushing of the nasolacrimal duct, which may be cannulated at either the proximal end and flushed towards the nose, or at the nasal ostium and flushed towards the eye. If the blockage is successfully alleviated, the duct should be carefully but copiously flushed. • An indwelling catheter or tubing might be sutured in place for 2–3 weeks to retain patency. • An ophthalmic eye drop containing an antibiotic and a steroid is prescribed for application up to four times daily until the inflammation has fully settled and then at reduced frequency for several days. • Systemic antibiotics may also be required. • If an underlying cause such as a sinus or tooth root problem is identified, this is treated appropriately. • Surgical correction is occasionally required if repeated flushing cannot alleviate the obstruction, establishing drainage with a more invasive procedure such as a conjunctivorhinostomy or a conjunctivosinusotomy. • Infectious blepharitis may be due to bacterial infection with Moraxella equi, Listeria monocytogenes or opportunistic bacteria. Fungal blepharitis might be caused by many organisms, depending on geographical exposure, and include Trichophyton, Microsporum and Histoplasmafarciminosus. • Traumatic blepharitis is also a common cause of inflammation. • Allergic blepharitis might arise as a result of a local or a systemic allergy, and blepharoedema may be the most striking sign. The allergen might be environmental, e.g. mold, dust, pollen, or it could be due to topical or systemic medication or shampoos, or a food allergy. • Immune-mediated blepharitis is uncommon, but might arise as part of the pemphigus foliaceus or bullous pemphigoid complexes, which will also affect other mucocutaneous junctions. • Solar blepharitis affects eyelids with little or no protective pigment which are exposed to UV light. Actinic blepharitis could be a precursor for later development of squamous cell carcinoma. • Parasitic infestation can result in blepharitis, and those that might affect the eye include Onchocerca cervicalis, Habronema muscae, Habronema microstoma and Draschia megastoma and Thelazia lacrymalis. Onchocerca principally affects the conjunctiva, with focal conjunctivitis present as nodules lateral to the limbus or as regions of de-pigmentation. Habronema causes mainly blepharitis, with thickened ulcerative caseous nodules on the eyelid margin or palpebral conjunctiva. Thelazia infestation might cause dacryocystitis but is often asymptomatic. • The conjunctival fornices and region behind the third eyelid should be examined carefully for the presence of a foreign body. • A swab should be submitted for bacterial and fungal culture and sensitivity. • Cytology of the affected region with scraping may allow more rapid diagnosis of the condition. If the cause is not evident, biopsy of the area may allow for an accurate histopathological diagnosis. • Infectious blepharitis should be treated as appropriate, based on culture and sensitivity. Systemic anti-inflammatory treatment might be required for allergic blepharitis, along with exclusion from the underlying trigger factor. • It is recommended that horses with solar blepharitis are shielded from the sun with UV-protecting eye wear, the provision of shade and with the application of sun block. • Habronema is effectively controlled with ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) but the lesions may also need to be treated with topical compresses, de-bulking, topical antibiotics or lubricants and systemic anti-inflammatories if severe. • Systemic ivermectin at the same dose is effective at controlling Onchocerca microfilaria, and this treatment will need to be repeated, as it is not effective against adult worms. Thelazia might be treated with topical irrigation with 0.5% iodine solution and 0.75% potassium iodide. Topical application of 0.03% echothiophate iodide or 0.025% isoflurophate has also been reported to be successful. • Diagnosis is normally made based on the characteristic clinical appearance. Any of the five broad categories of sarcoid (occult, nodular, verrucose, fibroblastic or mixed) may affect the periocular region (see p. 342). • Biopsy and histopathology provide definitive diagnosis. This also helps distinguish the lesion from granulation tissue, Habronema infestation, blepharitis, squamous cell carcinoma, papilloma or melanoma. • Periocular sarcoids present a therapeutic challenge as some of the treatment modalities, which are amenable to other parts of the body, are contraindicated around the eye because of the possibility of damaging the globe. • Historically, sarcoids were treated with topical irritants, such as engine grease, tea tree oil, and oil of rosemary, which served to stimulate the local immune system to mount a response against them. However they would cause a severe keratitis if they were allowed to come into contact with the cornea. • Surgical excision is usually difficult because of the size of the mass and the lack of available tissue for blepharoplasty procedures. It has also been suggested that sarcoids that recur after surgery are less amenable to further adjunctive treatments. • Immunotherapy using BCG injections at fortnightly intervals has been very successful at treating periocular sarcoids, although local and systemic anaphylaxis is a risk and should be anticipated with pre-treatment with systemic NSAIDs. • Chemotherapy with intralesional cisplatin or topical 5-fluorouracil has been reported to be successful, although 5-fluorouracil is irritant to the globe. • Cryotherapy and hyperthermia have both been reported with some success. Brachytherapy is reported to be very successful although facilities for radiation treatment must be available. • The prognosis is poorer when recurrence develops, therefore the initial treatment should be well thought out and thorough. • SCC may be suspected on the clinical appearance of the lesion. Eyelid SCC typically presents as an erosive, erythematous thickening of the eyelid. Third-eyelid SCC typically presents as a lobulated, irregular pink cobblestone-like mass on the third eyelid. • Definitive diagnosis requires biopsy and histopathology. Histopathology will also distinguish between plaque (carcinoma in situ), papillomatous, non-invasive or invasive SCC. • Gentle palpation of the orbital rim should be undertaken to assess for extension of the tumor. • A metastasis assessment should be made before treatment is considered, assessing the regional lymph nodes and salivary glands, the thorax, and the orbit and sinus for evidence of local extension. • Treatment of periocular SCC is challenging. While complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice, extensive eyelid re-construction is often not possible. • Removal of the entire third eyelid, over-sewing the remaining conjunctiva to prevent fat prolapse, may be curative for third-eyelid SCC. • Eyelid SCC may require surgical debulking with adjunctive treatment, or adjunctive treatment alone. Methods successfully employed include immunotherapy (BCG injections), chemotherapy (e.g. intralesional cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil), cryotherapy (double or triple freeze–thaw cycle to –25°C), brachytherapy (radioactive isotopes gold, iridium, radon, etc.) or hyperthermia (41–50°C). • The most recently reported treatment with a favorable outcome is photodynamic therapy (Giuliano et al 2008) although it is still undergoing further investigation as a suitable treatment modality. • There is a poor prognosis for eyelid SCC compared with third-eyelid SCC, and reported metastasis rates vary from 6% to 15%. • A careful ocular examination to attempt to identify other signs of glaucoma is indicated. These would include visual deficits, mydriasis, reduced pupillary light responses, corneal edema, mild iridocyclitis, retinal degeneration and optic nerve cupping. • Tonometry to measure the intraocular pressure is indicated. • If linear keratopathy is the only abnormality present, the condition is considered incidental and no treatment is required. • Diagnosis is made with the history of trauma and by careful examination of the eye. As the eye will be painful, sedation, regional nerve blocks and topical anesthesia will be required for a thorough examination. • The cornea should be examined with magnification to determine if any foreign body is still present. • Fluorescein stain is applied to assess the presence of corneal ulceration. The Seidel’s test is carried out simultaneously as follows. The corneal wound is examined carefully after liberal application of fluorescein dye. If the wound is leaking, a small stream of clear aqueous will flow through the concentrated fluorescein, appearing brighter green as it is diluted. This is a positive Seidel’s test. • If the cornea is stable and the eye cannot be examined thoroughly due to opacity in the ocular media, B-mode ultrasound is a useful method to look for lens luxation, lens capsule rupture, hemorrhage or inflammatory membranes in the vitreous and retinal detachment. • Treatment depends on the extent of the injury. Small corneal lacerations, which are not full thickness, can be treated medically as for corneal ulcers. This involves topical antibiotics and mydriatics, along with systemic NSAIDs. • If the edges of the corneal wound are edematous and therefore everted or irregular, or if the corneal wound is full-thickness, the wound should be surgically repaired. Direct simple interrupted corneal sutures are normally sufficient, but occasionally a conjunctival graft might be necessary to support healing. Systemic antibiotics and NSAIDs will be required as well as topical antibiotics and mydriatics. • Iris prolapse requires surgical repair. Ocular survival has been reported to be 80% after surgery with vision in 33% of horses with iris prolapse due to corneal lacerations. • The prognosis is best for corneal lacerations that do not involve any other ocular structures, and that are presented promptly for treatment. Corneal lacerations could potentially become complicated by bacterial or fungal infection, corneal melting, anterior synechiae, glaucoma, or uncontrolled uveitis due to lens capsule disruption causing lens-induced uveitis. Intraocular bacterial inoculation might result in endophthalmitis.

Disorders of the eye

Part 1 Orbit and globe

Congenital/developmental conditions

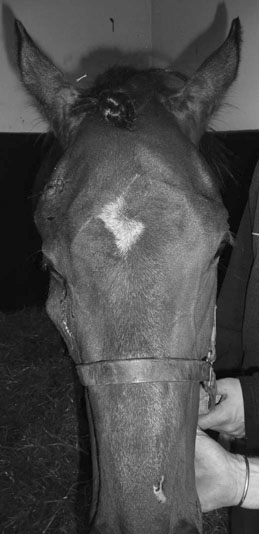

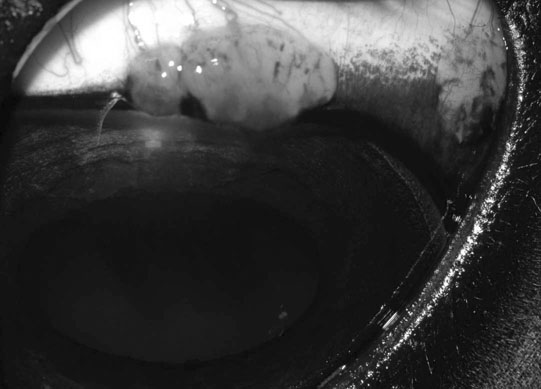

Microphthalmos/anophthalmos (Figs. 10.1–10.4)

Diagnosis and treatment

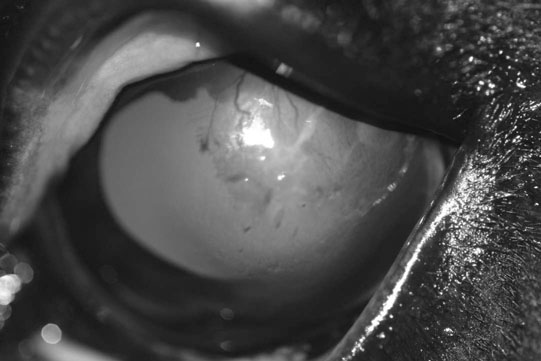

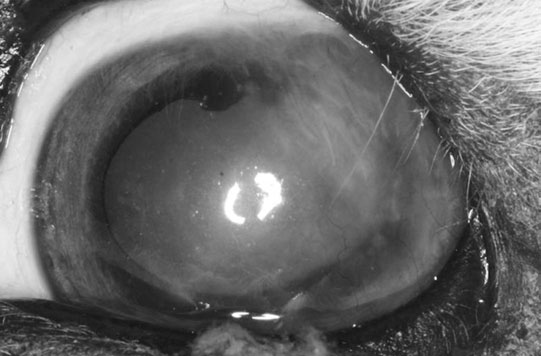

Anterior segment dysgenesis (Figs. 10.5 & 10.6)

Diagnosis and treatment

Non-infectious conditions

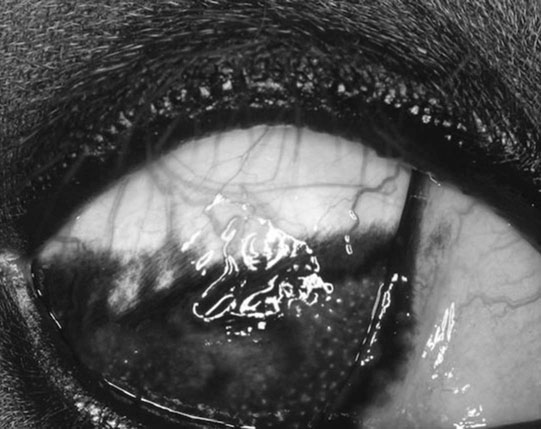

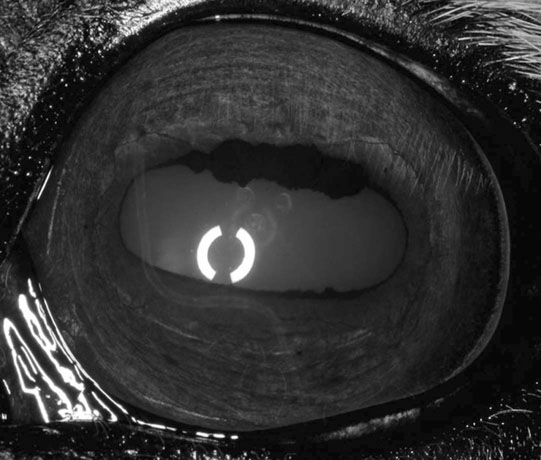

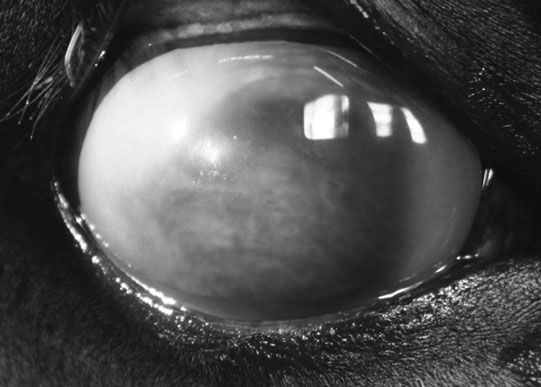

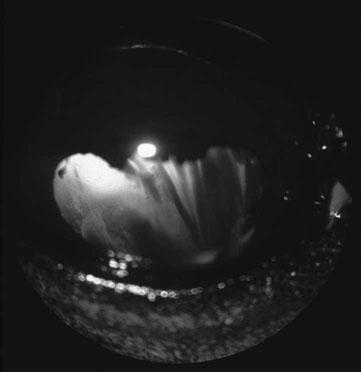

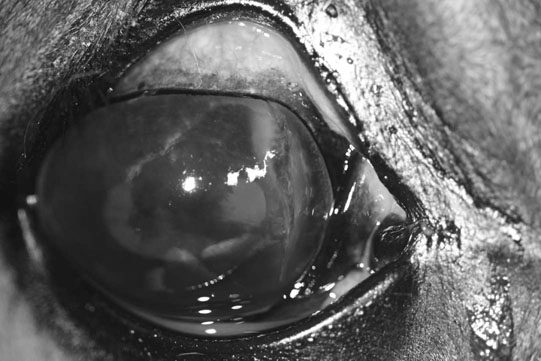

Phthisis bulbi (Figs. 10.7–10.9)

Diagnosis and treatment

Orbital fat prolapse (Fig. 10.10)

Diagnosis and treatment

Orbital neoplasia (Figs. 10.11–10.15)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Part 2 Eyelids, third eyelids, conjunctiva and nasolacrimal diseases

Congenital/developmental disorders

Entropion (Figs. 10.17 & 10.18)

Treatment

Cilia disorders (Fig. 10.19)

Treatment

Nasolacrimal duct atresia (Figs. 10.20 & 10.21)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Non-infectious disorders

Eyelid injury (Figs. 10.22–10.25)

Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis

Acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction (Figs. 10.26–10.29)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Non-infectious/infectious disorders

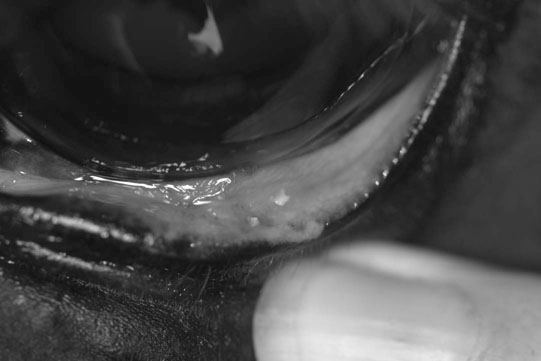

Blepharitis (Figs. 10.30–10.34)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Neoplasia

Eyelid sarcoids (Figs. 10.35–10.37)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid and third eyelid (Figs. 10.38–10.42)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Other adnexal tumors (Figs. 10.43–10.51)

Part 3 Cornea

Congenital/developmental conditions

Dermoids (Fig. 10.52)

Linear keratopathy (Fig. 10.53)

Diagnosis and treatment

Non-infectious disorders

Corneal trauma (Figs. 10.54–10.60)

Diagnosis

Treatment and prognosis

Corneal foreign bodies (Figs. 10.61–10.67)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Disorders of the eye