CHAPTER 169 Diseases of the Uterus

The uterus is a tubular organ that nourishes the equine embryo for a mean of 11 months from the time of its entry from the uterine tubes via the highly differentiated muscular uterine papilla until the fetus is completely grown and mature. The fetus can grow in the uterus because the fetal membranes and the endometrial portion of the uterus combined form the placenta, which provides the fetus with the blood supply and nutrients needed for growth. Once fetal maturation is complete, the uterus plays an important role in initiating expulsion of the fetus into the birth canal during parturition.

REPRODUCTIVE EXAMINATION OF THE NONPREGNANT MARE

Palpation Per Rectum and Transrectal Ultrasonography

The veterinarian examining the mare should be familiar with the reproductive anatomy and function to be able to differentiate between physiologic and pathologic changes. Palpation of the cervix and assessment of its tone are very important because the cervical tone and, to a lesser extent, the uterine tone, are indicative of circulating levels of progesterone. Mares under progesterone influence during diestrus or pregnancy should have a closed cervix that feels tubular and firm on palpation per rectum.

ENDOMETRITIS

Persistent inflammation of the uterus, whether or not accompanied by bacterial or fungal infection, is an important cause of decreased reproductive efficiency in brood mares. Endometritis encompasses endometrial changes associated with acute or chronic inflammation. These changes are modulated by the action of a local immune system and influenced by the hormonal milieu. Transient endometritis is normal in all mares that are mated naturally or artificially inseminated. This inflammation occurs in response to contact with the semen and contaminants introduced into the uterus at mating or by artificial insemination. This apparently normal inflammatory response subsides within 2 to 3 days in the so-called resistant mares, which show an absence of intraluminal uterine fluid as detected by transrectal ultrasonography as early as 12 hours after breeding. Mares that show accumulation of intrauterine fluid in the uterus 24 hours after mating are classified as susceptible. Susceptible mares have delayed uterine clearance that results in persistent mating-induced endometritis, a recognized clinical entity that has been incriminated as an important cause of infertility in broodmares.

Bacterial Endometritis

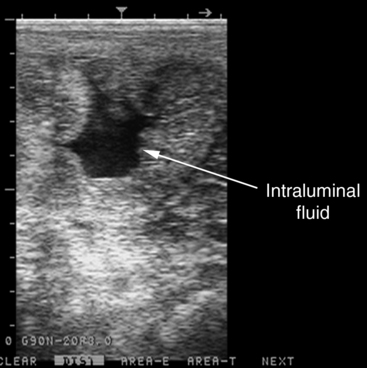

The pathogenesis of bacterial endometritis in the mare is complex and has not been completely elucidated. Many mares that are not pregnant at the 14-day pregnancy check or that have early fetal loss do not have vaginal discharge. However, before and during the palpation per rectum, one should observe the vulva for exudate that might indicate uterine infection. Vaginal speculum examination may reveal variable volume of exudate at the external cervical os and on the cranial vaginal floor. Transrectal ultrasonography should always be performed to provide information about any abnormal uterine contents, especially if the mare is in estrus. The volume and echogenicity of intraluminal fluid should be noted. Detection of fluid during diestrus invariably indicates that the mare has active endometritis(Figure 169-1). Analysis of the mare’s cycling pattern may indicate shortened interestrous intervals induced by endogenous release of luteolytic prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) from the inflamed uterus. Endometritis should be ruled out in mares that do not become pregnant after being properly managed, especially those that have distinct endometrial edema at pregnancy examination on days 12 to 14 postovulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree