Chapter 12 Diseases of the Urinary System

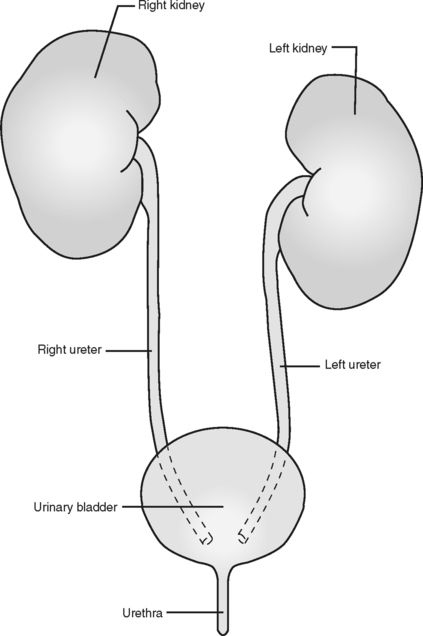

Anatomically, the urinary system is composed of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra (Fig. 12-1). The main job of the urinary system is waste removal, although it is also instrumental in red blood cell production, the regulation of water and electrolyte balances, and control of blood pressure. The system is a blood plasma balancer. It processes blood plasma by adjusting the water and electrolyte content, removes waste materials not needed by the body, and returns those necessary substances to the systemic circulation. It also regulates the pH of the plasma. The final product is urine, which is stored for elimination.

Figure 12-1 The urinary system is made up of two kidneys, two ureters, one urinary bladder, and one urethra.

(From Colville T, Bassert JM: Clinical anatomy and physiology for veterinary technicians, St Louis, 2002, Mosby, by permission.)

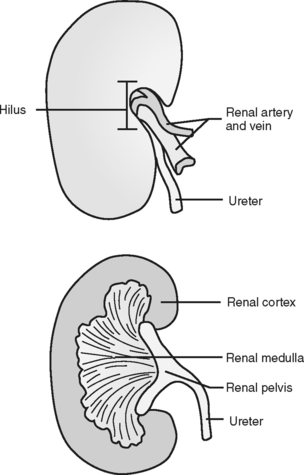

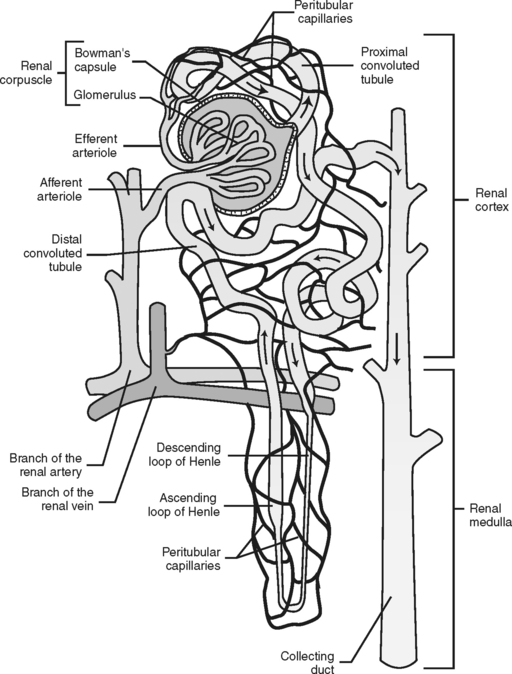

The kidneys are located in the retroperitoneal space along the vertebral column from T13-L3. Internally, the kidney is divided structurally into the cortex (the outer region) and the medulla (the inner region) (Fig. 12-2). The “filtration units,” or glomeruli, are concentrated in the cortical region, whereas the “concentration/exchange tubules,” or nephron loops, are found in the medulla (Fig. 12-3). Blood enters the kidney and is filtered through the capillaries of the glomerulus. The nephron loop concentrates the filtrate and reabsorbs vital nutrients. The urine passes into the ureters and then on to the bladder for storage before elimination.

Figure 12-2 Frontal section of right kidney.

(From Colville T, Bassert JM: Clinical anatomy and physiology for veterinary technicians, St Louis, 2002, Mosby, by permission.)

Figure 12-3 Fluid flow through the nephron.

(From Colville T, Bassert JM: Clinical anatomy and physiology for veterinary technicians, St Louis, 2002, Mosby, by permission.)

CYSTITIS

Feline Cystitis (Idiopathic [Interstitial] Cystitis)

Cats with undocumented bacteriuria should not be treated with antibiotics. Needless antibiotic treatment only results in an increased number of antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Cats should be given places to hide; toys and scratching poles allow cats to exercise normal play behavior and reduce stress, which has been shown to help in the treatment of this disorder.

DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT

Canine Cystitis (Bacterial Cystitis)

DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT

Prevention

FELINE UROLITHS AND URETHRAL PLUGS

Feline Uroliths

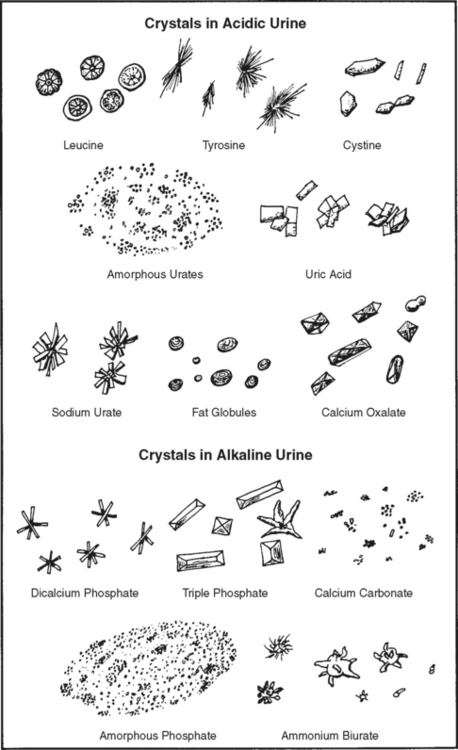

A number of different minerals can be found in feline uroliths (Fig. 12-5). These include the following:

Figure 12-5 Various types of crystals that may be found in urine.

(From Hendrix CM, Sirois M: Laboratory procedures for veterinary technicians, ed 5, St Louis, 2007, Mosby, by permission.)

In most cases, the cause of urolith formation cannot be determined, although studies show that diets high in magnesium produce struvite uroliths experimentally in cats. Obese, older cats (>2 years) appear to be predisposed to urolith formation. There appears to be no breed predisposition for struvite uroliths; however, Burmese, Himalayan, and Persian breeds have a greater prevalence of calcium oxalate uroliths. Cats that form uroliths typically have concentrated urine with altered pH (either too alkaline or too acidic). Cats with uroliths may be asymptomatic or may present with signs of lower urinary tract disease or urethral obstruction. Spontaneous reabsorption of uroliths has been documented.