Chapter 8 Diseases of the Teats and Udder

The udder of a dairy cow consists of four separate glands suspended by medial and lateral collagenous laminae. The medial laminae are more elastic, especially cranially, than the lateral laminae and are paired. Caudally, the medial laminae are more collagenous and originate from the subpelvic tendon. The lateral laminae are multiple, inserting at various levels of mammary tissue, and originate from the subpelvic tendon caudally and external oblique aponeurosis cranially. The medial and lateral laminae provide udder support that is essential for udder conformation and for solid attachment to the ventral body wall. The external pudendal artery constitutes the major blood supply to the udder; the artery courses through the inguinal canal along with the pudendal vein and lymph vessels to supply the craniolateral portion of the mammary gland. Caudally, the internal pudendal artery branches into the ventral perineal artery at the level of the ischiatic arch and courses caudally to the vulva, along the perineum to the base of the rear quarters. The caudal superficial epigastric vein (subcutaneous abdominal vein or milk vein) is the major venous return from the mammary gland. Located superficially along the ventral abdomen, it courses cranially to the “milk well” where it enters the abdomen to join the internal thoracic vein, draining first into the subclavian vein, and finally into the cranial vena cava. Lymph drainage moves dorsally and caudally to the superficial inguinal (mammary, supramammary) lymph nodes, which can be palpated by following the rear quarter dorsally until it ends, then palpating deep just above the gland along the lateral laminae. Although the prefemoral (subiliac) lymph nodes that are located in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle, approximately 15 cm dorsal to the patella, are not strictly drainage lymph nodes of the udder, they should be palpated as part of the routine physical examination of cattle. Because of their regional proximity and combined lymphatic drainage with the supramammary lymph nodes into the medial iliac lymph nodes, many cows with mastitis have obvious lymphadenopathy of the prefemoral lymph nodes, and they are easily palpable.

UDDER

Breakdown or Loss of Support Apparatus

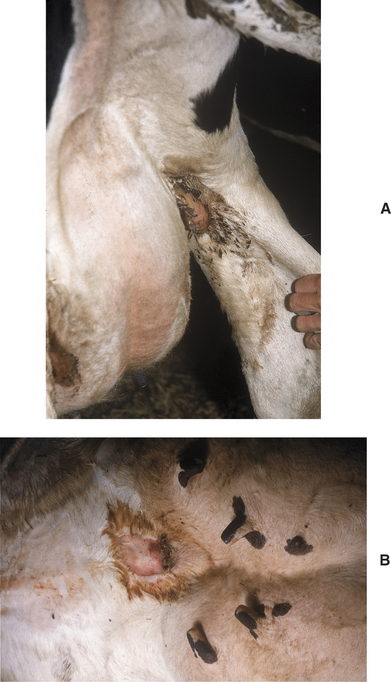

All these various deficiencies in udder support predispose to udder edema, teat and udder injuries, and mastitis. Edema is worsened by the pendulous nature of the udder, reduced venous and lymphatic return, and trauma. Injuries to the teat and udder in cows with pendulous udders (Figure 8-1) result from environmental trauma that includes contact of the udder with flooring when the cow is recumbent and direct damage from claws and dewclaws or from being stepped on by neighboring cows. Mastitis is predisposed to by environmental contamination of the teats and udder, teat injuries that affect milkout, and imperfect milkout caused by persistent edema in the floor of the udder. In some cows—especially those with severe loss of median support—it may not be possible to attach a milking machine claw simultaneously to seriously deviated teats. The result often is mastitis or culling because of milking difficulties. In addition, purebred cattle that are classified are discriminated against in classification score if these undesirable mammary characteristics are present.

Hematomas

Signs

Soft tissue swellings immediately cranial to the udder are most common in lactating dairy cattle (Figure 8-2), whereas extreme swelling in the escutcheon region ventral to the vulva and dorsal to the rear quarters is more common in dry cows (Figure 8-3). The swelling may be fluctuant, soft, or firm, depending on the amount of blood causing the distention; usually it is painless and cool. Rare instances of hematomas between the base of the udder and ventral body wall also have been encountered.

Abscesses

Etiology

Udder abscesses may appear anywhere in the mammary tissue or adjacent to the glands. Frequently skin puncture with subsequent abscessation is suspected when obvious abscesses appear in quarters having completely normal secretion and no evidence of mastitis. Endogenous abscesses can form secondary to mastitis with abscessation, as is typical of mastitis caused by Arcanobacterium pyogenes. However, this discussion will be confined to udder abscesses requiring percutaneous drainage, and discussion of mastitis origin abscesses will be addressed in the mastitis section.

Abscesses appear as firm, warm swellings that may be either distinct or indistinct from gland parenchyma (Figure 8-4). Palpation of the swelling may be painful to the affected cow. Milk from the affected quarter usually is normal, and the abscesses tend to be well-encapsulated.

Treatment

Thrombophlebitis and Abscessation of the Milk Vein.

Thrombophlebitis of the mammary vein is an occasional complication of venipuncture at this site (Figure 8-5). This vessel seems attractive for the intravenous (IV) administration of pharmaceuticals, particularly in pit parlors and for producers for whom its size and accessibility make it a less challenging alternative compared with the jugular or coccygeal veins. However, the consequences of mammary thrombophlebitis with respect to udder symmetry and future production are sinister enough that it should never be used in show or valuable individual cows. It should only be used under considerable duress even in grade cattle. Abscesses may develop secondary to phlebitis from the use of contaminated needles or subsequent to hematoma formation when vascular damage and perivascular leakage occur as the cow resists the procedure. As with all cases of thrombophlebitis there is a risk of embolic spread, potentially causing endocarditis or nephritis. If treatment is initiated immediately following the inciting attempted venipuncture, antiinflammatory and antimicrobial therapy is indicated. However, veterinary attention is often only sought after abscessation has already occurred, at which time the goal of therapy should be surgical drainage followed by antimicrobial therapy. It can be challenging to avoid significant blood loss when lancing such abscesses because of the highly vascular nature of the region, and ideally the procedure should be performed under ultrasound guidance. The bacterial species implicated include the common pyogenic anaerobes, and antimicrobial therapy should include beta-lactam antibiotics. Treatment of valuable cattle may include rifampin under appropriate extra-label drug use guidelines.

Udder Cleft Dermatitis

Signs

A fetid odor similar to that found in septic metritis or retained placenta emanates from areas of moist dermatitis in the groin area or more commonly the ventral median area of the udder. Skin necrosis may be mild or severe. In the worst cases, large patches of skin (10 to 30 cm in length) may be peeled off. Matted hair, scabs, and necrotic skin are present (Figure 8-6, A and B). Myiasis may occur in warm weather. In some first-calf heifers, groin infections can be so severe that lameness may occur.

Treatment

For dairies that request therapy, a commercially available topically applied wound spray (Granulex Aerosol Spray, Pfizer Inc., Exton, PA) consisting of a mixture of castor oil, balsam of Peru, and trypsin has been used successfully by field veterinarians for the treatment of udder cleft dermatitis. The spray is marketed for administration in humans and has been effective for treatment of decubitus in bedridden patients. Other compounded remedies have been recommended for the treatment of udder cleft dermatitis, but given the current drug compounding regulations of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), these formulations cannot be recommended for use in food-producing animals. Patients that have developed cleft fold pyodermas secondarily to udder edema should be treated with diuretics (furosemide, 1 mg/kg) to reduce edema and anaerobiosis in the skin of the mammary gland. Diuretics are calciuretic and kaluretic, so during diuretic treatment of postpartum cows, calcium status should be monitored, and if the cow shows weakness, lassitude, and cold extremities, she should be given IV calcium gluconate and 100 g of potassium chloride orally.

Udder Dermatitis

Etiology

Udder dermatitis may be associated with a multitude of chemical, physical, and microbiologic causes.

Treatment

Physical causes of dermatitis are best treated by preventing further exposure to the specific physical cause and by symptomatic therapy. Sunburned cows must be kept inside or provided shade if at pasture. Cool water compresses followed by aloe or lanolin ointments to deter skin cracking and peeling caused by dryness are helpful. Udder supports may help prevent sunburn. Frostbite is best prevented by therapy for excessive udder edema and keeping periparturient cows well bedded for warmth. Periparturient cows in free stalls during extreme cold are at greatest risk because free stall beds usually are poorly bedded for warmth. Once frostbite has occurred, careful sharp debridement of necrotic tissue and protection against further injury are the only potentially effective treatments.

Edema

Signs

Physiologic udder edema may start in the rear udder, fore udder, in the left or right half of the udder, or symmetrically in all four quarters. Edema tends to be most prominent in the rear quarters and floor of the udder (Figure 8-7). Cows with moderate to severe udder edema usually have a variable degree of ventral edema extending from the fore udder toward the brisket.

Pathologic edema persists longer than physiologic edema. Pathologic edema may be present for months following parturition or for the entire lactation. The tendency for pathologic edema is increased in cows with breakdown of udder support structures, and conversely pathologic udder edema may contribute to breakdown of udder support structures. Therefore severe edema may affect a cow’s longevity and classification in some instances.

Treatment

In herds with endemic udder edema, nutritional consultations are imperative to evaluate anion-cation balance. Total potassium, total sodium, and serum chemistry to profile affected and nonaffected cows should be performed. Diets with anionic salt supplementation and those with added antioxidants may show some tendency to diminish udder edema in affected herds. Water and availability of free choice salt or salt-mineral combinations should be included in the nutritional evaluation.

MAMMARY TUMORS

Lymphosarcoma

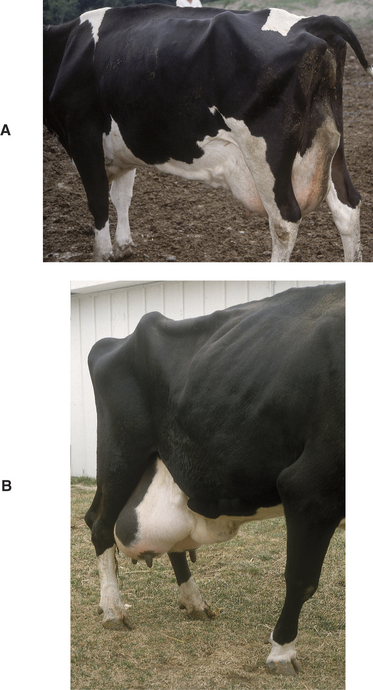

Lymphosarcoma is the most common tumor to appear within the gland and associated lymph nodes in dairy cattle. Focal and diffuse infiltration of the gland with lymphosarcoma and rarely adenocarcinoma has been observed (Figure 8-8, A and B). The mammary gland is hardly ever the only site of lymphoma infiltration, however. Usually tumor masses in other target organs or lymph nodes supersede mammary involvement. Affected glands may merely appear edematous rather than firm, and secretions may appear normal. Diffuse lymphocytic infiltration of the udder may appear similar to the diffuse mild edema that develops in hypoproteinemic cattle. The mammary lymph nodes (superficial inguinal) may be enlarged because of lymphosarcoma or chronic inflammation and should routinely be palpated during physical examination.

Signs

Affected cows have a varied clinical presentation ranging from focal enlargement to diffuse and massive udder enlargement. Some squamous cell carcinomas are ulcerated, firm, and pink with a malodorous smell. Precursor papilloma or epithelioma masses may have been observed by the owner. Fibropapillomas or warts are obvious and are of little concern.

Udder Amputation

Hemimastectomy or radical mastectomy is rarely performed in cattle. Indications for this in valuable or pet cattle would be neoplasia, chronic incurable mastitis, and/or suspensory apparatus failure that causes the udder to sag and be persistently traumatized (Figure 8-9). Individual animals that undergo udder amputation must be in good general condition. Significant blood loss can occur with udder amputation because of the vascularity of the mammary gland. Cattle with septic mastitis or in poor physical condition should not undergo udder amputation until their physical condition is significantly improved.

The cow must be placed in dorsal recumbency and preferably under general anesthesia. A fusiform skin incision is made to facilitate subsequent skin closure. Therefore the lateral incisions must extend to the junction between the middle third and dorsal third of the udder to allow sufficient skin for closure under minimal tension. Following skin incision, the dissection is first directed toward the inguinal canal where the pudendal arteries and then vein are ligated. The procedure is repeated on the contralateral side. Using curved Mayo scissors, the loose fascia on the proximal aspect of both lateral laminae is incised starting cranially and extending caudally until the left and right perineal arteries and veins are located and double ligated. To minimize systemic blood loss (through retention in the mammary gland), the caudal superficial epigastric veins are ligated last. The lateral laminae are then sharply transected and dissection extended on the dorsal aspect of the mammary gland to complete the excision.

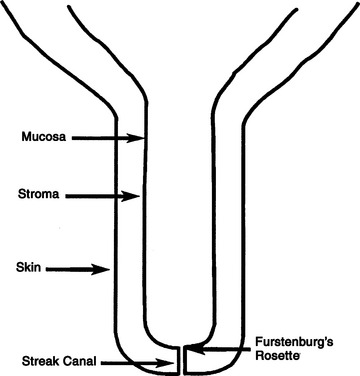

TEAT DISEASE

The tissue layers in the teats of dairy cattle include skin, inner fibrous, stroma, and mucosa. Stroma is a vascular and muscular layer containing veins that drain to the large subcutaneous venous plexus at the juncture of teat and udder. The inner fibrous layer is a thin membrane that is interposed between the mucosa and the stroma (Figure 8-10).

Figure 8-10 Schematic of the bovine teat to illustrate the basic anatomic terms used in this chapter.

Congenital Anomalies

Etiology and Signs

Supernumerary teats are the most common congenital abnormality, which is likely heritable in dairy cattle. There has been little genetic selection away from this trait in heifers simply because it is not reported back to artificial insemination stud services and because the problem is so easily treated. Supernumerary teats are extremely common in certain lines of cattle—especially Guernseys. Usually one to four extra teats is observed, although more can occur. Generally the supernumerary teats are placed caudal to the rear quarter teats or between the rear and forequarter teats. These “extra” teats require treatment, lest functional glands evolve that would likely become infected because they cannot be milked effectively. Such infections provide a chronic source of infection for other quarters in the herd.

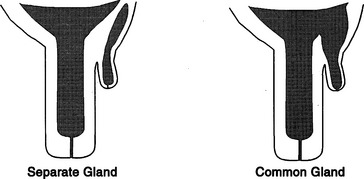

Supernumerary teats that are joined to one of the four major teats have been called webbed or “Siamese” teats. These may appear as distinct teats or only as small raised areas on the wall of one of the major teats (Figure 8-11, A to D). Although these teats frequently have a separate gland of their own, they may communicate with the teat or gland cistern of the major teat (Figure 8-12). In either case, these joined teats require special treatment and careful differentiation from simple supernumerary teats, lest future production of the gland be compromised.

Figure 8-12 Co-joined supernumerary teats may communicate with a separate gland or the gland of the major teat.

Keratinized corns or keratomas on the teats of heifers have been recognized. These structures are tightly adherent to the teat end, grow progressively, and their physical weight stretches and elongates the affected teat (Figure 8-13).

Treatment

Heifer calves should be examined for the presence of supernumerary teats at a routine time during the first 8 months of life. Most veterinarians perform this examination when vaccinating 4- to 8-month-old calves for brucellosis. Following restraint of the heifer, the supernumerary teats are grasped and cut off with scissors at the point where the skin of the teat meets the skin of the udder. A suitable antiseptic is applied to the wound following removal, but sutures generally are not used except when a cosmetic appearance is required immediately. Care must be exercised when removing supernumerary teats, lest a true teat be removed accidentally.

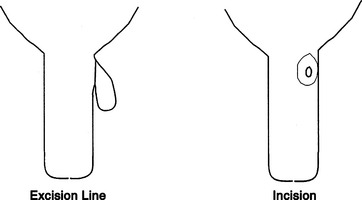

Supernumerary teats cojoined to a major teat (webbed teats) need to be repaired surgically rather than just snipped off. The repair should be performed when the teat is large enough to be manipulated easily and then sutured. Many surgeons prefer to operate on animals at approximately 8 months of age. Aseptic technique is essential because infection of the future mammary gland is a major risk. Following an 8- to 12-hour fast, the heifer is sedated with xylazine (4 to 5 mg/kg/100 lb body weight, IV), tied in dorsal recumbency, and the hair is clipped from the udder near the extra teat. Following routine preparation, a fenestrated drape is placed, and the supernumerary teat is excised by scalpel or scissors. This excision is nearly flush with the skin of the main teat but should leave enough skin to close the wound (Figure 8-14). After excision, the mucosa of the rudimentary teat should be closed with fine synthetic absorbable suture (e.g., Monocryl, Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ), such as 3-0 or 4-0. The skin and stroma are sutured as a single layer using interrupted vertical mattress sutures or alternatively closed with individual layers. Many suture materials are suitable for stroma and skin closure, but absorbable sutures such as 3-0 or 4-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ) or Monocryl are popular because they do not require subsequent removal and associated restraint. Antibiotics such as IM penicillin (22,000 IU/kg) should be administered preoperatively and for 2 to 3 days postoperatively.

Teat-End Injuries

Etiology

Teat ends are the most common site of mammary injury in dairy cattle and are the most common reason for owners to seek veterinary consultation regarding the teats of dairy cattle. Teat-end injuries may affect the sphincter muscle, the streak canal, or both. Injuries to the teat end are caused by the digit or medial dewclaw of the ipsilateral limb of the affected cow or by injury from neighboring cows stepping on the teat. Teat-end injuries are more common in cows with pendulous udders or in those that have lost support laminae. Acute injuries cause inflammation, hemorrhage, and edema within the distal teat stroma and sphincter muscle. Subsequent soft tissue swelling in the teat end mechanically interferes with proper milk release from the streak canal. In addition, the streak canal epithelium and keratin may be disrupted, crushed, lacerated, partially inverted into the teat cistern, or partially inverted from the teat end. Occasional distal membranous obstruction occurs as a result of teat injuries followed by local fibrosis (Figure 8-15). Obvious laceration of the distal teat skin may be present but frequently is not. When present, lacerations tend to be at the teat end. Degloving injuries to the teat end are also occasionally encountered subsequent to claw or limb trauma when the teat becomes trapped against solid flooring. Repeated or chronic teat-end injury leads to fibrosis of the affected tissues, granulation tissue at the site of any mucosal or streak canal injury, and continued problems with milkout. Subclinical teat-end injury has been associated with defective milking machine functions such as increased vacuum pressures or overmilking.

Signs

Painful soft tissue swelling of the distal teat is the cardinal sign of acute teat-end injury. The skin may be hyperemic or bruised (Figure 8-16). The cow resents any handling or manipulation of the teat end and objects to being milked. A combination of mechanical interference with milkout and pain-induced reluctance to let down milk predisposes to incomplete milkout from affected quarters. Mastitis is the feared and frequent sequela to incomplete milkout in cows with teat-end injuries. The cow is further predisposed to mastitis if the physical defense mechanism of the streak canal is compromised.

Figure 8-16 Acute teat-end injury showing diffuse swelling and a blood clot extruding from the streak canal.

Treatment

Treatment of acute teat-end injuries should address both the injury and any management factors that might lead to further injury, such as overcrowding, lack of bedding, and milking machine problems.

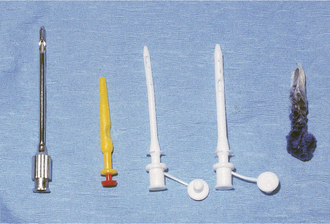

The best treatments for acute teat-end injury include symptomatic antiinflammatory therapy and reducing further trauma to the teat end. Each injury must be assessed individually. If milkout is simply reduced but not prevented, milkers sometimes use dilators of various types between milkings to stretch the sphincter muscles, thus allowing machine milkout. If milkout is difficult, it is best to avoid further machine milking and to utilize a teat cannula to effect milking twice daily when the other quarters are machine milked. If cannulas are used, the milker must exert extreme care to avoid exogenous inoculation of the teat cistern with microbes. Therefore the teat end must be cleaned gently, and alcohol must be applied before introducing the sterile cannula. Usually a disposable 1-in plastic cannula is used for this purpose. After complete milkout, the teat end is dipped as usual and a repeat dip performed in 10 minutes. Alternatively, some practitioners recommend indwelling plastic cannulas that may be capped between milkings. Several types are available commercially. In addition to facilitating milkout, these indwelling cannulas act as dilators that may reduce the possibility of streak canal adhesions or fibrosis. Teat dilators impregnated with dyes are not favored because they seem to induce chemical damage to the steak canal. However, many owners use such dilators anyway (Figure 8-17). Wax and silicone teat inserts that may retain patency with less iatrogenic mastitis are commercially available. The wax insert is recommended for initial use, but it disintegrates after several days. Insertion of silicone rubber inserts after the wax has disintegrated is recommended. The inserts have comparable efficacy and antibacterial properties. Both inserts are readily available in the United States. Alternatively, milk can be drained from the gland, intramammary antibiotics infused, a wax teat insert (Figure 8-18) placed in the teat, followed by icing and bandaging the teat with no further milkout for 2 to 3 days.

Nursing care is helpful but unfortunately is often not available on modern dairy farms. Soaking the injured teat with concentrated Epsom salts in a cup of warm water for 5 minutes twice daily helps reduce edema and inflammation. It is most important to avoid further trauma to the teat end and to minimize the risks for developing mastitis. Therefore avoidance of machine milking is indicated for at least several days whenever possible.

Problems that have been associated with teat-end lesions include crusts, necrosis, ulceration (Figure 8-19), and mastitis. All result in continued pain to the patient and mechanical interference with milkout as a result of scab or exudate buildup. Gentle soaking in warm dilute Betadine solution (Purdue Pharma, Cranbury, NJ) followed by removal of crusts or exudate aids complete milkout. Teat injury predisposes the cow to mastitis, particularly infections with gram-positive organisms.

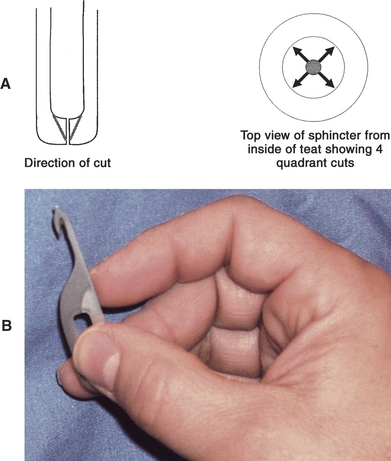

For surgical correction of obstructed teat ends, the teat should be washed, cleaned, and disinfected with alcohol (Box 8-1). The cow should be restrained and/or sedated before surgery. A teat bistoury or knife, preferably one with a small single cutting edge and blunt tip, should be used. The aim of this procedure is to relieve the stricture in the streak canal through two to four angled cuts made at 90-degree intervals (Figure 8-20, A and B). The cuts are made into the dorsal sphincter muscle but tapered so as not to cut the distal sphincter or teat end. We prefer the use of a Larsen teat blade because it allows a better control of the dept of the cut and facilitates the creation of a tapered incision. These radial incisions release the sphincter and frequently are the only treatments required. Some veterinarians use wax inserts to reduce hemorrhage following this procedure and to diminish subsequent inflammation and swelling that may impede milkout.

Box 8-1 Preparation for Teat Surgery or Treatment

Surgical thelotomy or repair of full-thickness lacerations and fistulae

A Moore’s teat dilator also has been used for sphincter muscle fibrosis. This instrument is inserted into the teat following routine preparation and advanced slowly to stretch the sphincter muscle without sharp surgery.

Teat-end necrosis or ulceration is difficult to manage because buildup of scab material in the crater-like ulcer recurrently interferes with milking. Gentle soaking and mechanical removal of the scabs are necessary for milkout. A mild teat dip with glycerin or lanolin for softening is indicated in these patients. Some require surgical manipulation if continued irritation or overmilking damages the sphincter muscle or dorsal streak canal. When teat-end necrosis is observed in more than one cow in a herd, the milking machinery and procedures should be examined carefully to rule out excessive vacuum pressure and physical or chemical irritants in teat dip or bedding (Figure 8-21).

Acquired Teat-Cistern Obstructions

Etiology

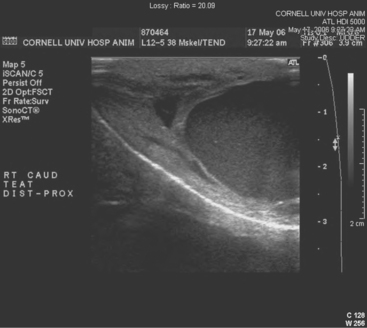

Teat-cistern lesions resulting in obstructed milk flow may be focal or diffuse. Most teat-cistern obstructions result from proliferative granulation tissue, mucosal injury, or fibrosis—all secondary to previous teat trauma. Occasional cases have no history of previous acute injury. Focal and diffuse lesions in the cistern cause an increasing degree of flow restriction that interferes with effective milk delivery to the streak canal during machine milking. With ultrasound examination, obstruction at the junction of the gland and teat cistern can be visualized (Figures 8-22 and 8-23). This type of obstruction leads to slow refill of the teat cistern such that they cannot be milked by machine. However, they can be milked by teat cannula or siphon. In addition to fixed lesions, floating objects known as “milk stones” or “floaters” may cause problems in milkout because they are pulled into the teat and mechanically interfere with milking. These floaters may be completely free or may be attached to the mucosa by a pedunculated stalk. Mucosal detachments also are encountered secondary to external teat trauma. The detached mucosa folds onto the opposite teat wall, causing a valve effect as milking progresses. Submucosal hemorrhage or edema from previous trauma is thought to cause detached mucosa; the problem may not be apparent until resolution of the submucosal fluid allows the detached mucosa to become mobile within the cistern.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree