Chapter 6. Diseases of the orbit

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Vascular lesions of the orbit126

Orbital fat prolapse (herniation)126

Diseases of the orbit may originate within the structures of the bony orbit (that vary between species), or in the orbital soft tissues, including the globe, extraocular muscles, and variable secretory tissues such as the zygomatic salivary gland, as well as the rich neurovascular supply to these tissues. However, many diseases affecting the orbit represent the extension of inflammatory or neoplastic processes from adjacent tissues. Thus, important anatomic considerations in the diagnosis of orbital disease also include the proximity of the oral and nasal cavities, the para-nasal sinuses, muscles of mastication, and brain.

INFLAMMATORY DISEASE OF THE ORBIT

Orbital inflammatory disease is relatively common

• In the COPLOW collection, orbital inflammation is usually diagnosed in conjunction with panophthalmitis, in globes that were enucleated because of intraocular inflammation that had concurrent orbital inflammation

• This combination is most common in dogs and there are 84 cases in the COPLOW collection.

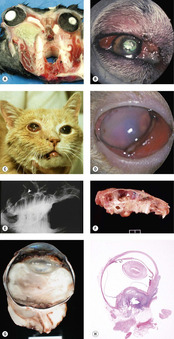

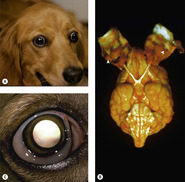

Orbital cellulitis or abscess secondary to tooth root inflammation (Fig. 6.1)

• Most common in dogs, rabbits, chinchillas, and horses

▪ Periodontitis extending to the root apex

▪ Pulpitis due to exposure of the root canal from trauma or caries, which occurs less frequently in domestic animal species than in humans

• Consider the possibility of trauma and iatrogenic spread of infection to the orbit during dental procedures

▪ There are six cases in the COPLOW collection in which orbital suppurative inflammation and panophthalmitis occurred shortly following a dental procedure.

|

| Figure 6.1 Orbital abscess. (A) Gross photograph of sectioned rabbit skull with orbital abscess related to dental disease. (B) Golden Retriever, 5 years old: periocular swelling and serosanguineous discharge was due to a dental abscess. (C) DSH, 8 years old: this globe is exophthalmic, the conjunctiva is hyperemic and chemotic, and the right side of the face is swollen secondary to a dental abscess. (D) DSH, 5 years old: the third eyelid is hyperemic and prolapsed over the exophthalmic globe. Exposure keratitis resulted in poor visualization of the anterior segment. (E) Rabbit skull radiograph showing periapical bone lysis (arrow). (F) Gross photograph of the skull in (E) showing abscess extending into the calvarium (arrow). (G) Gross photograph of canine globe showing an orbital abscess in the posterior pole as well as panophthalmitis. (H) Subgross photomicrograph of a similar canine globe with abscess in the orbital tissues at the posterior pole. |

Orbital inflammation secondary to deep orbital soft tissue injury (Fig. 6.2)

Most of these cases are presented because there is panophthalmitis and the orbital inflammation itself is not well-characterized, either clinically or histopathologically.

|

| Figure 6.2 Orbital and episcleral inflammation. (A) Miniature Poodle, 10 years old: the exophthalmic globe has severe conjunctival hyperemia, corneal edema and a dense cataract. Zarfoss KM, Dubielzig RR, Eberhard ML, and Schmidt KS. Canine ocular onchocerciasis in the United States: two new cases and a review of the literature. Vet. Ophthal. 8: 51–57, 2005. (B) English Bulldog, 5 years old: the conjunctiva and sclera are hyperemic and thickened. Adjacent cornea is edematous and vascularized in this exophthalmic globe. (C,D) Gross photographs of canine globes showing orbital soft tissue inflammation and fistulous tracts. (E) Subgross photomicrograph of a canine globe showing orbital fibrosis with suppurative inflammation. (F) Photomicrograph of the episcleral tissues from a dog showing a porcupine quill within an inflammatory fistula. |

Penetrating injury from the oral cavity

• Most severe disease is seen in the inferior tissues of the orbit, dependent to the globe

• Fistulous and suppurative processes generally characterize the inflammatory response

• The degree of fibrosis is variable but, in some cases, can dominate the pathology

• Foreign bodies can be challenging to identify and are rarely found on histopathology. Orbital foreign bodies are more commonly identified in dogs than in cats (82 dogs versus 12 cats in the COPLOW collection)

▪ Plant material is most common

– 41 documented cases in dogs

– Four documented cases in cats

▪ Porcupine quills may penetrate the orbit directly or migrate from adjacent tissues. There are two such cases in the COPLOW collection.

Penetrating injury from external trauma, including bite-wounds

Such injury is more likely to occur in species such as the dog and cat that have a relatively ‘open’ bony orbit.

• Most severe disease is present within the lateral or superior orbit, rather than inferior orbit

▪ If the wound is lateral, then it is less likely to be sampled with the standard vertical section of the globe. Special instructions from an alert clinician are essential if the primary lesion is to be located

• Other findings similar to penetrating injury from the oral cavity.

Orbital inflammation associated with specific organisms

Mycotic infections

Infection of the orbit may result from hematogenous spread in disseminated, systemic mycoses, or by extension of local infection from the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, or from the globe. The systemic mycoses are considered in greater depth in Chapter 9.

Blastomyces dermatitidis

There are five cases in the COPLOW collection in which a diagnosis of blastomycosis was made from orbital biopsy specimens.

• Four in dogs and one in a cat.

Cryptococcus neoformans

There are three cases in the COPLOW collection, in which the diagnosis was made from orbital biopsy specimens.

• Two in cats and one in a dog

• The canine case had concurrent malignant sarcoma in the orbit.

Coccidioides immitis

There are two canine cases represented in the COPLOW collection, both submitted from the South-western United States.

Candida spp.

There are two feline cases of localized orbital candidiasis in the COPLOW collection.

Aspergillus spp.

There are three canine cases of orbital aspergillosis in the COPLOW collection, all of which were associated with nasal aspergillosis. This is consistent with previously published reports.

Although not represented in the COPLOW collection, feline orbital aspergillosis has been reported in the literature.

• Affected cats may or may not show clinical evidence of disease in the paranasal sinuses or nasal cavity

• There is an apparent breed predisposition for Persian cats.

Bacterial infections

Bacteria were observed in specimens from 15 cases in the COPLOW collection that had orbital inflammation. Nine canine cases, three rabbits, one cat, one horse and one chinchilla.

• In none of these cases was the identity of the bacterial organism established. This may reflect a failure to submit samples for microbiological culture, or difficulty in isolating organisms due to specific culture requirements.

Parasitic infestations

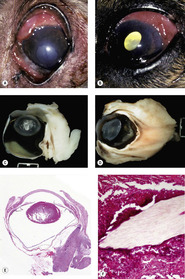

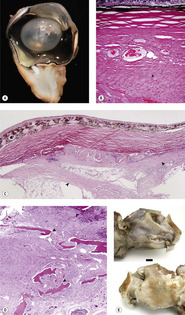

Canine episcleral onchocercosis (Fig. 6.3)

• This disease of emerging importance is most common in Mediterranean Europe, with reports from Greece, and lesser numbers from Hungary and Germany

▪ In the European cases, the morphologic features of adult worms have been reported as being consistent with Onchocerca lupi (from wolves). However, this is controversial because nucleotide sequences for this canine form appear to be unique within the genus, and this canine disease may represent host switch and site shift that has resulted in a new Onchocerca species

• There are 12 cases in the COPLOW collection from dogs in North America

▪ All originated in California or neighboring Western states

▪ The parasites involved have previously been identified as Onchocerca lienalis but this remains controversial, as the definitive identity of the parasite has not yet been established

– Cattle are the definitive host for Onchocerca lienalis; the adult parasites live in the gastrosplenic ligament

– Onchocerca spp. have a relatively narrow host range, and patent infection (as the presence of adult male and female worms, with microfilaria within the adult female worms in the orbital tissue suggests) would only be expected if dogs, or a closely related species were the definitive host

• Morphological features of canine ocular onchocercosis

▪ There is a nodular infiltrative lesion in the substantia propria of the conjunctiva, extending into the episcleral tissue and orbital fascia

▪ Granulation tissue admixed with eosinophils, lymphocytic inflammation and macrophages

– It is not essential to find eosinophils in the infiltrate

▪ In the posterior aspect of the subconjunctival mass lesions and extending all the way around the episcleral tissues, there are cavities containing adult male and female parasites, surrounded by a pure population of epithelioid macrophages

▪ Male and female worms are often seen together, and the females contain microfilaria

• Morphologic features useful for the identification of Onchocerca spp.

▪ These worms are easily identified as filarial nematodes because they have an obvious cuticle and have coelomyarial musculature, as well as digestive and reproductive system structures

▪ The adult females are easily recognizable as filarial worms because they contain microfilaria

▪ The following features may help distinguish Onchocerca spp. from Dirofilaria spp.

– The cuticle of adult female Dirofilaria spp. worms, have ridges that run longitudinally and therefore are only seen when the worms are sectioned in cross-section

– The cuticle of adult female Onchocerca spp. worms consists of two distinct layers with interior striae and, on the exterior surface, ring-like, circumferential ridges which are only seen when the worms are cut in the longitudinal plane.

|

| Figure 6.3 Canine orbital Onchocerca. (A,B) Gross photograph and subgross photomicrograph showing a proliferative nodule in the orbit and bulbar conjunctiva associated with infestation by the nematode parasite Onchocerca sp. (C) Higher magnification photomicrograph, of the boxed area in (A,B) showing nematodes within granuloma-lined clefts in the orbital episcleral tissue of a dog. (D) Photomicrograph showing an adult female nematode. The inset shows a circumferential ridge (*), which is characteristic of Onchocerca. |

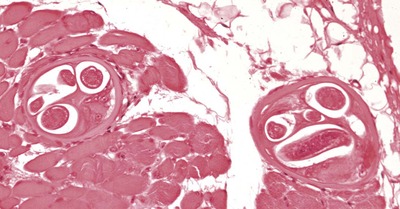

Infestation of extraocular muscles with Trichinella spiralis (trichinosis) (Fig. 6.4)

There are two cases of canine extra-ocular trichinosis in the COPLOW collection.

Comparative Comments

• Both cases were in dogs with clinical histories of generalized wasting and fever that were suggestive of systemic disease.

Comparative Comments

The spectrum of inflammatory diseases of the orbit encountered in human pathology differs rather markedly from that seen in the veterinary pathology laboratory. Orbital cellulitis in humans is most commonly caused by extension of an inflammation from the paranasal sinuses. Its cause includes common bacterial infections, with the most commonly identified organisms being Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, and other Gram-positive rods. Infection may also incur by endogenous routes, as with bacteremia or septic embolization, and from exogenous sources following trauma. Fungal infections may occur in immunocompromised patients and are usually caused by Mucor or Aspergillus species. Echinococcus granulosus is the most common parasitic cyst seen in the orbit.

|

| Figure 6.4 Trichinosis. Photomicrograph showing Trichinella spiralis in the extraocular skeletal muscle from a dog. |

Canine extraocular polymyositis (Fig. 6.5)

This diagnosis is generally made based on clinical presentation alone. Extraocular muscle biopsy is seldom performed to support the clinical diagnosis, and there are no cases represented in the COPLOW collection; however, the pathology of the condition has been well described.

Comparative Comments

• Golden Retrievers are over-represented

• Affected dogs are generally 6–18 months old and more often female than male

• In many cases, an antecedent stressor, such as recent kenneling, surgery or estrus is reported prior to the onset of clinical signs

• The condition is bilateral but not always symmetrical and, in its acute phase, causes exophthalmos, chemosis, and retraction of the upper eyelid without protrusion of the third eyelid

• The muscle pathology is dominated by a lymphocytic infiltrate within the muscle tissue. CD3+ lymphocytes predominate

• Chronic fibrosing extraocular myositis with restrictive strabismus

▪ Has been reported in young large-breed dogs and Shar Peis

▪ May be unilateral or bilateral

▪ Clinical presentation is of rapid onset and progression of enophthalmos and severe ventro-medial strabismus leading to visual impairment

▪ May represent a chronic phase of extraocular muscle polymyositis

▪ Characterized by fibrosis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate restricted to the extraocular muscles.

Comparative Comments

This condition has many features similar to Graves’ disease in humans.

• The orbital manifestations of severe ophthalmopathy with exophthalmos in Graves’ disease usually begin in adults. Older males are affected more often than younger females, in contrast to the mild form of thyrotoxic exophthalmos

• Patients with this severe form of disease are often hyperthyroid, but patients may be hypothyroid or euthyroid

• The disease is an inflammatory extraocular myopathy, with a predominantly T-cell infiltrate

• In the later stages of disease the affected extraocular muscle tissue may become fibrotic

• Thyroid orbitopathy is the most common cause of unilateral and bilateral exophthalmos in adults. This usually involves extraocular muscles and is characterized by inflammatory enlargement of extraocular muscles and subsequent scarring.

|

| Figure 6.5 Extraocular polymyositis of Golden Retrievers. (A) Golden Retriever, 18 months old: characteristic bilateral axial exophthalmia with increased scleral ‘show’ is present. (B) Golden Retriever, 10 months old: gross photograph of the brain, eyes, optic nerve and still-connected extraocular muscles showing thickening and pallor in the extraocular muscle tissues. The arrows point to two swollen extraocular muscles. Reproduced with permission from Carpenter JL, Schmidt GM, Moore, FM, Albert DM, Abrams KL and Elner VM. Canine bilateral extraocular polymyositis. Vet. Pathol. 26: 510–512, 1989. (C) Golden Retriever, 9 months old: the bilateral exophthalmia was also associated with chemosis and hyperemia of the conjunctiva. |

Masticatory muscle myositis

• There is a predisposition for young, large-breed dogs

• May cause exophthalmos, due to displacement of the globe secondary to swelling of pterygoid and/or temporalis muscles that form soft-tissue boundaries of the open, canine orbit

• Subsequent fibrosis of the pterygoid and temporalis muscles may lead to enophthalmos

• Muscle biopsy and detection of serum antibodies against type 2M muscle fibers may be helpful in the diagnosis of masticatory myositis

• Generalized polymyositis and infectious causes of myositis (including neosporosis, toxoplasmosis and leishmaniasis) should be considered in the differential diagnosis of extraocular and masticatory myositis.

Other, poorly characterized, orbital sclerosing conditions

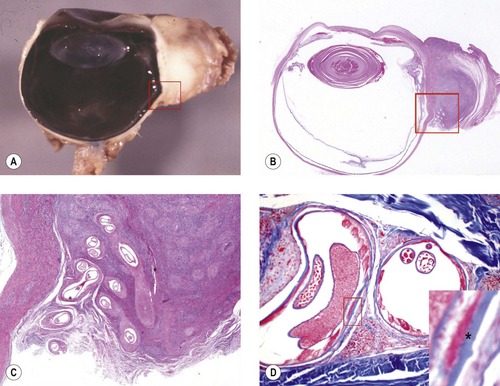

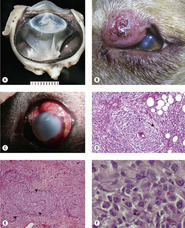

Feline restrictive orbital sarcoma (feline sclerosing pseudotumor) (Fig. 6.6)

There are 10 cases diagnosed in the COPLOW collection.

Comparative Comments

• This condition has a very characteristic clinical appearance:

▪ There is variable exophthalmos, with very pronounced reduction in globe motility

▪ Retraction of the upper eyelid contributes further to severe corneal exposure and desiccation, which is often associated with ulcerative keratitis

• Morphologically, the condition is characterized by a mixture of bland spindle cells, associated with variable amounts of extracellular collagen deposition and perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes

▪ The spindle cell infiltrate and collagen accumulation extends from the conjunctival substantia propria to the episcleral tissue at the posterior pole of the globe

• Gradual progression, over weeks to months, to involve the second eye is typically reported

• Involvement of the skin, lip, and/or oral mucosa, with pronounced gingival thickening, has also been reported

• The etiopathogenesis of this condition has not yet been elucidated

• Evaluation of the head from cats after euthanasia, reveals bone lysis and neoplastic infiltration of the empty orbit. At the end of life mass lesions are more likely to be a part of the syndrome

• The progressive, nature and the histological appearance of the proliferative lesions are more consistent with a form of fibrosarcoma rather than with a non-neoplastic inflammatory disease.

Comparative Comments

Pseudotumor in humans:

• Categorized as granulomatous, or non-granulomatous

• Sclerosing pseudotumor is a subtype of non-granulomatous pseudotumor

• The hallmark of sclerosing pseudotumor is the early appearance of fibrosis that is out of proportion to the lymphocytic inflammation

– This is similar to idiopathic restrictive orbital sarcoma or sclerosing pseudotumor in cats.

|

| Figure 6.6 Feline restrictive orbital sarcoma (orbital sclerosing pseudotumor). (A) Gross photograph of feline globe and orbital tissues showing orbital contents bound together by bland neoplastic fibrous tissue in restrictive orbital sarcoma. (B) Photomicrograph showing sclera and spindle-cell proliferative reaction in the episcleral orbital tissue (*). (C) Low magnification photomicrograph showing fibrous tissue (arrows) wrapped around the sclera, adipose tissue and facial planes. (D) Photomicrograph showing the orbit from a cat eventually euthanized with feline restrictive orbital sarcoma showing neoplastic tissue associated with bone lysis (arrows). (E) Gross photograph of the head of the cat euthanized with feline restrictive orbital sarcoma. The upper image shows the side of the head not affected with neoplastic tissue and the lower image is of the side of the head affected. The affected side shows a blanket of neoplastic tissue covering the facial planes and obscuring muscles. Notice that there is no well-defined mass lesion, even in this late stage of disease. |

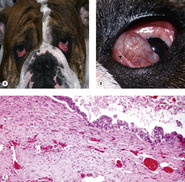

Canine systemic histiocytosis (Fig. 6.7) (see Ch. 7 for detailed discussion)

There are seven cases with orbital involvement diagnosed in the COPLOW collection: two in Bernese Mountain dogs, three in Labrador Retrievers, and two in other breeds. The three forms of canine histiocytosis that have been described include:

1. Cutaneous histiocytosis, the most benign and localized – this diagnosis has not been made in the COPLOW collection.

2. Systemic histiocytosis, which has been diagnosed in the COPLOW collection.

3. Malignant histiocytosis, the most malignant of the three, based on morphological and biological behavior. Malignant histiocytosis has not been diagnosed in the COPLOW collection.

|

| Figure 6.7 Canine systemic histiocytosis. (A) Gross photograph of a globe with systemic histiocytosis, causing a diffuse swelling in the uveal tissues. (B) Clinical photograph showing an eyelid nodule with systemic histiocytosis. (Image courtesy of Jane Cho.) (C) Clinical photograph showing episcleral tissue swelling associated with systemic histiocytosis. (D,E) Photomicrographs of systemic histiocytosis showing vasocentric histiocytic infiltrate (arrows). (F) Higher magnification photomicrograph showing atypical histiocytic cells, which predominate in systemic histiocytosis. |

The morphologic features useful in diagnosing systemic histiocytosis are as follows:

• Solid nodular tumors characterized by sheets of only moderately dysplastic histiocytes, that lack anaplastic features

• Minimal lymphocytic or neutrophilic involvement

• No classical granulomatous nodules

• Evidence of vasocentricity

▪ This ranges from histiocytic cells tightly surrounding blood vessels, to blood vessel destruction and obliteration

– Vasocentric infiltration is considered a very important diagnostic consideration at COPLOW

• Reticulin fibers surrounding the histiocytes.

Systemic histiocytosis may regress spontaneously but often requires aggressive anti-inflammatory chemotherapy

Comparative Comments

Comparative Comments

Specific causes of non-infectious orbital inflammation in humans include: ruptured dermoid cysts; idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease (pseudotumor); sarcoidosis; amyloidosis and systemic autoimmune vasculitides. The most common of this latter group is Wegener’s granulomatosis, characterized by a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation of the arterioles and venules. Other vasculitides include: systemic lupus erythematosus and polyarteritis nodosa. Kimura’s disease occurs most commonly in Asians, and it is characterized by vascular proliferation, lymphoid hyperplasia, and eosinophilic inflammation. Less commonly seen non-infectious inflammations include: necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with paraproteinemia, pseudorheumatoid nodules, foreign body granulomas, histiocytosis X, sinus histiocytosis, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and Erdheim–Chester disease.

CYSTIC LESIONS OF THE ORBIT

Acquired conjunctival cyst (Fig. 6.8)

There are 13 cases of acquired cysts diagnosed in the COPLOW collection.

• Acquired cysts are the result of the traumatic displacement of epithelial tissue which then develops into a cystic lesion is the displaced location

▪ Acquired cysts can develop after trauma or surgery

▪ Most cases occurred as a complication following enucleation surgery

• Conjunctival cyst is characterized by the following features:

▪ Fully-differentiated conjunctival epithelium or stratified squamous epithelium surrounded by a fibrous capsule

▪ Inflammation may or may not be a feature

▪ Some cases have excessive keratinization within the cyst.

|

| Figure 6.8 Conjunctival epithelial cysts of the orbit. (A) DSH, 7 years old: the right globe was enucleated 3 months previously. A soft swelling was present within the bony orbit at the arrow. (B) Gross photograph of the cyst dissected from the orbit of (A). (C) Golden Retriever, 2 years old: the dark area below the globe represents a large inferior subpalpebral cyst. (D) This brown serous fluid is from the fine needle aspirate of the cyst shown in (C). (E,F) Photomicrographs showing the inner epithelium and the fibrous wall of conjunctival cysts in dogs. |

Dermoid cyst

• These are rare congenital cystic lesions that may occur within the orbit. Although isolated canine and equine cases are reported in the veterinary literature, this diagnosis is not represented in the COPLOW archive

• These lesions are present at early age, probably from birth, but may not present clinically until adulthood due to slowly progressive enlargement of the cyst

• Morphologic features of dermoid cyst include:

▪ Contain fully-differentiated but disorganized epidermal structures such as stratified squamous epithelium, hair follicles, sebaceous glands or sweat glands

▪ Rarely they contain other structures of surface ectodermal origin.

Salivary or lacrimal ductular cyst (Fig. 6.9)

There are eight cases of orbital salivary ductular cysts in the COPLOW collection.

• These cysts can be associated with the lacrimal gland or the zygomatic salivary gland

• Morphologic features characteristic of ductular cyst

▪ In order to make the diagnosis of ductular cyst, there has to be an epithelial lining to the inner aspect of the cyst

▪ The cyst wall may be thin and fibrous and devoid of inflammation. However, the adjacent associated glandular tissue often demonstrates an inflammatory infiltrate and fibrosis

▪ There may or may not be evidence of a mucinous component within the cyst.

|

| Figure 6.9 Mucocele of the lacrimal glands of the nictitans. (A) English bulldog, 9 months old: bilateral hypertrophy glands nictitans were surgically treated with the pocket technique 3 months before the photograph. (B) This photograph of the left eye of (A) shows the large cystic structure protruding from the bulbar surface of the nictitans. The arrow points to the normal free lid margin of the nictitans. (C) Photomicrograph showing the cyst epithelium, which is cuboidal epithelium and the loose connective tissue immediately outside the cyst.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|