Chapter 10 Diseases of the Integumentary System

We acknowledge and appreciate the original contributions of Drs. David E. Anderson and D. Michael Rings, whose work from the previous edition of this book has been incorporated into this chapter.

Anatomy and Relevant Physiology

The skin functions as a protective barrier to the environment. It also aids in thermoregulation, acts as a sensory organ, and communicates through the secretion of chemicals.1,2 Both sheep and goats have relatively thin skin, with an average thickness of 2.6 mm in sheep and 2.9 mm in goats.1 Hair is important for thermoregulation. A short, thick hair coat is best for regulating body temperature during high environmental temperatures, whereas long, fine hair coats are most efficient at low environmental temperatures. Thus shearing sheep when environmental temperatures are still low is not without risk. Likewise, failure to complete shearing by the time hot weather arrives may predispose the animals to heat exhaustion. Secondary hairs make up a greater proportion of the hair coat compared with primary or guard hairs in goats and sheep. In Angora goats and sheep, three types of wool are recognized: true wool, Kemp fibers, and hair fibers. True wool fibers are fine and tightly crimped. Kemp fibers are coarse, relatively short, and poorly crimped. Hair fibers are somewhere in between wool and Kemp fibers in their morphologic characteristics. Guard hairs are undesirable in wool-bearing breeds, because the medulla makes the hair brittle and this hair type does not take up dye well. Small secondary hairs of goats are nonmedullated.

Specialized cells such as the sweat gland allow cooling.

The epidermis is composed of five layers—from outermost to innermost, stratum corneum, stratum lucidum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale. The stratum basale produces new cells that continuously move up to replace the sloughing cells of the stratum corneum. The melanocytes of the stratum basale and hair follicles are primarily responsible for the color of the hair coat. All melanins arise from a common metabolic pathway that is catalyzed by a copper-containing enzyme. One of the signs of copper deficiency, therefore, is a lighter-than-normal color of the hair coat. Besides the obvious physical barrier presented by the epidermis and hair or wool, chemical and microbial barriers to infection also are recognized: The secretion produced by the sweat and sebaceous glands has antimicrobial properties. Included within this secretion are fatty acids, inorganic salts, interferon, transferrin, complement, and immunoglobulins. Increased hydration of the skin greatly increases microbial populations. Normal skin flora can inhibit colonization of other potential pathogens. However, some skin pathogens also may be components of the normal flora. For example, dermatophytes and Staphylococcus aureus can be recovered from clinically normal mammals that do not develop clinical disease.

Approach to Diagnosis

Historical data should include the signalment of the animal: species, breed, age, gender, weight, and color. Some breeds have a higher likelihood of developing specific disease conditions (Table 10-1). Therefore breed information is useful to assess for susceptibility. The clinician should note details concerning the origin of the animal and exposure risks. Origin includes whether the animal was born and raised on the farm, purchased by farm contracts, purchased through sale barns, or imported from another state or country. Exposure risks include transportation to another farm; commingling in sales, shows, or fairs; farm tours involving children or livestock owners; and diseases that are endemic to the particular farm. In the last case, the clinician also should note when the last outbreak occurred. Chronologic data are important in making a differential diagnosis. The date of the first observation of clinical signs should be determined, the duration of clinical signs should be evaluated, and details regarding the progression of the disease within the affected animals should be described. The region of the body affected and the spread of disease to other regions of the body also are important. Often the presenting disease state is so severe that the point of origin cannot be determined by physical examination. Assessment of whether the disease has spread from one animal to another within the flock or herd is particularly important. Finally, the veterinarian may assemble a detailed chronology of any treatments applied, the dosage and route used for administration, and the duration of treatment.

TABLE 10-1 Breed Predilections for Skin Diseases in Sheep and Goats

| Disease | Breed(s) With Recognized Predilection |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous asthenia | |

| Congenitohereditary photosensitivity | |

| Viable hypotrichosis | Dorset sheep |

| Hereditary goiter | |

| Epidermolysis bullosa | |

| Scrapie | Suffolk sheep |

Modified from Scott DW: Large animal dermatology, Philadelphia, 1988, WB Saunders.

Clinical signs are important in the development of a differential diagnosis. They can vary widely and depend on the tissues involved in the disease process. Possibilities in the differential diagnosis are most easily determined early in the course of disease, when the primary lesions are abundant (Table 10-2). As the disease progresses, secondary lesions such as infection, thickening, crusting, and hair loss may overwhelm the primary disease and make assessment of skin disease extremely difficult. Therefore animals with newly emerging disease should be selected for examination.

TABLE 10-2 Typical Distribution of Lesions Associated With Selected Diseases of the Skin

| Area Involved | Disease | Primary Lesion Type |

|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | Dermatophytosis | Papulocrustous |

| Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Demodicosis | Papulonodular | |

| Elaeophoriasis | Ulcerative | |

| Fly bites | Papulocrustous | |

| Actinobacillosis | Nodular | |

| Clostridiosis | Edematous | |

| Sarcoptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Contagious viral pustular dermatitis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Ovine viral ulcerative dermatitis | Ulcerative | |

| Goat pox | Pustulocrustous | |

| Sheep pox | Pustulocrustous | |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Vesiculopustular, crusts | |

| Zinc deficiency | Crusts | |

| Contact dermatitis | Variable | |

| Viral papillomatosis | Papulonodular | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Nodular, ulcerative | |

| Ears | Dermatophytosis | Papulocrustous |

| Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Sarcoptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Fly bites | Papulocrustous | |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Vesiculopustular, crusts | |

| Ergotism | Necrotizing | |

| Fescue toxicosis | Necrotizing | |

| Frostbite | Necrotizing | |

| Photodermatitis | Edematous, necroulcerative | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Nodular, ulcerative | |

| Mucocutaneous | Contagious viral pustular dermatitis | Pustulocrustous |

| Goat pox | Pustulocrustous | |

| Sheep pox | Pustulocrustous | |

| Bluetongue | Erythema, edema | |

| Zinc deficiency | Crusts | |

| Bullous pemphigus | Vesiculoulcerative | |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Vesiculopustular, crusts | |

| Dermatophytosis | Papulocrustous | |

| Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Nodular, ulcerative | |

| Dorsum | Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous |

| Fly bites | Papulocrustous | |

| Psoroptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Contact dermatitis | Variable | |

| Ventrum | Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous |

| Fly bites | Papulocrustous | |

| Sarcoptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Contact dermatitis | Variable | |

| Goat pox | Pustulocrustous | |

| Sheep pox | Pustulocrustous | |

| Contagious viral pustular dermatitis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Zinc deficiency | Crusts | |

| Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection | Abscesses | |

| Trunk | Dermatophytosis | Papulocrustous |

| Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Psoroptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Psorergatic mange | Alopecia, pruritus | |

| Keds | Alopecia, pruritus | |

| Ovine fleece rot | Moist dermatitis | |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Vesiculopustular, crusts | |

| Demodicosis | Papulonodular | |

| Caprine viral dermatitis | Papulonodular | |

| Scrapie | Excoriation, pruritus | |

| Vitamin A deficiency | Hyperkeratosis | |

| Iodine deficiency | Alopecia, scaling | |

| Biotin, niacin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid deficiency | Alopecia, scaling, crusts | |

| Vitamin C–responsive dermatosis | Alopecia, erythema, purpurea | |

| Copper deficiency | Depigmentation | |

| Hindquarters | Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous |

| Chorioptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Legs and feet | Dermatophytosis | Papulocrustous |

| Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Chorioptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Contact dermatitis | Variable | |

| Elaeophoriasis | Necroulcerative | |

| Clostridiosis | Edema | |

| Sarcoptic mange | Papulocrustous | |

| Zinc deficiency | Crusts | |

| Vitamin C–responsive dermatosis | Alopecia, erythema, purpurea | |

| Ovine viral ulcerative dermatitis | Ulcerative | |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Vesiculopustular, crusts | |

| Tail | Psoroptic mange | Scales, pruritus |

| Selenosis | Alopecia | |

| Coronary band | Pemphigus foliaceus | Vesiculopustular, crusts |

| Bluetongue | Erythema | |

| Contagious viral pustular dermatitis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Ergotism | Edema | |

| Fescue toxicosis | Edema | |

| Dermatophilosis | Pustulocrustous | |

| Zinc deficiency | Crusts |

Modified from Scott DW: Large animal dermatology, Philadelphia, 1988, WB Saunders.

Changes in skin and hair pigmentation are uncommon in most ruminant diseases. Exceptions include the hair pigment lightening seen in cattle with chronic copper deficiency and molybdenosis and the black wool pigment that develops in blackfaced sheep after skin injury (abrasions, laceration, chronic irritation). The development of dark pigmentation also has been observed in Saanen goats exposed to excessive sunlight.

Lesion location can be useful in establishing a differential diagnosis (see Table 10-2). Regions commonly affected in the early stages of skin disease include the face, ears, feet, udder, and perineal region. Fungal skin infections more commonly occur on the face, neck, and ears, whereas bacterial skin diseases also affect the feet, udder, and perineum. Nutritional deficiencies typically involve all regions to various degrees. Photosensitization is more severe in areas that receive little protection by the hair coat and those with slight or no pigmentation. Ectoparasite lesions are most severe on the feet, face, and ears.

Diagnostic Tests

Although many skin diseases are diagnosed on the basis of clinical signs and the intuition of an experienced veterinarian’s sense of the significance of these and other findings, specific diagnosis requires confirmation by laboratory tests (Table 10-3).

TABLE 10-3 Tests Used for Diagnosis of Skin Disease

| Cause of Skin Disease | Tests Used |

|---|---|

| Parasites | |

| Fungi | |

| Bacteria | |

| Viruses | |

| Allergy | Intradermal skin tests |

| Miscellaneous pathologic conditions | Histopathologic techniques—examination of biopsy sections, immunofluorescence tests, antinuclear antibody tests, use of special stains |

Modified from Scott DW: Large animal dermatology, Philadelphia, 1988, WB Saunders.

Microbial Culture

Bacterial and fungal cultures can be used to determine the presence of pathogenic organisms. Culture results may be challenging to interpret, because some cultured microbes may be part of the normal resident flora of the skin of sheep and goats (Table 10-4). Bacterial cultures may be obtained by aspirating pustules, abscesses, and other nodules. If a skin biopsy is to be performed, material for bacterial culture may be obtained from a sample of skin tissue. The clinician cleanses the desired sample area with alcohol and obtains a hair sample from the periphery of an active lesion. Cultures for dermatomycotic agents must be set up on special media. Fungal cultures may require weeks in a favorable environment before a positive or negative result can be reported.

TABLE 10-4 Normal Microbial Inhabitants of the Skin in Sheep and Goats

| Species | Bacteria | Fungi |

|---|---|---|

| Goat | Staphylococcus aureus | Aspergillus |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | Mucor | |

| Sheep | Bacillus | |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| Micrococcus | ||

| S. aureus | ||

| S. epidermidis | ||

| Streptococcus |

Modified from Scott DW: Large animal dermatology, Philadelphia, 1988, WB Saunders.

Biopsy

Skin biopsy is most useful to identify lesions consistent with ectoparasites and allergic and autoimmune disease. Skin biopsy is indicated when a lesion is unusual in appearance or location, has failed to respond to treatment, is suspected to be neoplastic, or is persistently ulcerative or exudative. It also can be used to rule out various pathologic conditions in the differential diagnosis. Biopsy specimens should be obtained from primary lesions and ideally should include the junction of normal and abnormal skin. Commercial skin biopsy instruments (with internal diameters of 4 to 8 mm) provide the best-quality samples for pathologists. Areas with minimal skin tension should be chosen. A needle and scalpel blade can be used to harvest a skin sample, or the entire lesion may be submitted if surgical excision has been performed. Full-thickness skin biopsy is recommended to allow examination of all layers of the epidermis and dermis. Sedation or tranquilization of the patient may be required. The clinician may clip the hair surrounding the area of skin biopsy; however, hair emerging from the skin sample is desirable to enhance the pathologist’s evaluation. Therefore only minimal clipping should be performed, and a razor blade should not be used. A small amount of lidocaine hydrochloride 2% is deposited in the subcutaneous tissue deep within the specimen. This should be done carefully and immediately before biopsy, because the side effects of lidocaine include vascular dilatation and edema, both of which may confuse histologic evaluation. Many pathologists prefer that skin specimens be preserved attached to a wooden plank such as a piece of a tongue depressor. Fixatives for skin samples include 10% neutral buffered formalin for routine light microscopy and glutaraldehyde for electron microscopy. Skin biopsy specimens may be fixed with Michel’s fixative or fresh-frozen without fixative if immunohistochemistry analysis or other such testing is desired. In one study, shrinkage was similar for formalin-fixed and for fresh-frozen specimens (approximately 20%).3 Skin biopsy specimens should be submitted to a veterinary pathologist experienced in the interpretation of histopathologic findings in skin. Because skin histology varies dramatically among species, a pathologist experienced in evaluation of the skin of sheep and goats is preferable. If preferred by the clinician or the owner, the biopsy site can be closed (using a simple interrupted or cruciate suturing pattern) with either absorbable or nonabsorbable material.

Viral Diseases

Contagious Ecthyma (Sore Mouth/Orf/Contagious Pustular Dermatitis)

Contagious ecthyma—also called “sore mouth,” orf, and contagious pustular dermatitis—is a unique viral skin disease caused by a parapoxvirus. It is seen primarily in sheep and goats but also has been reported in other wild and domestic ruminants and in humans. The morbidity in naive herds or flocks will approach 100%, but mortality rates rarely exceed 1%. Death, if it occurs, usually is due not to the infection itself but rather to secondary complications such as pneumonia or starvation. The causative virus can persist in the soil for years and has survived in a laboratory environment at room temperature for 20 years.1 A conflicting report indicated that the virus was undetectable in scabs shed naturally from healed lesions.2 Nevertheless, once on the farm, it is considered to be on the farm forever. Outbreaks tend to occur around lambing or kidding time, when newly susceptible offspring are present. Transmission may be through direct contact with clinically affected animals or on fomites contaminated by the clinically affected, or may occur indirectly by contact with virus-contaminated soil or shed scabs, and some evidence points to the possibility of spread by nonclinical carriers.3 Transmission by nonclinical carriers has been disputed, however: “[Orf virus] does not cause latent infections in animals that recover from clinical disease, but clinically healthy animals that are moved from infected to noninfected premises or transported in contaminated vehicles can act as mechanical carriers.”4 The virus typically finds entry through a break in the skin. Thus the disease tends to be most prevalent in young animals, sometimes in association with tooth eruption.5 The incubation period is 3 to 14 days. It is one of the more significant zoonotic skin diseases of sheep and goats and is considered to be extremely painful for affected humans. Veterinarians and producers should take precautions to avoid exposure by wearing disposable gloves for treatment or examination in suspected cases.

Clinical Signs

The clinical presentation is relatively unique, with scab-like lesions appearing most often on the lips and muzzle and in the oral cavity (Figure 10-1). Lesions appear as crusty proliferations at mucocutaneous junctions, similar to fever blisters. Initial lesions appear as papules, followed by vesicles and pustules and scab formation. Scabs heal over and drop off in 1 to 4 weeks. A typical mild course of the disease in 10- to 21-day-old lambs has been reported, with resolution occurring beginning at 7 days.5 Lesions also may develop on the teats and udders of nursing dams, often as a result of suckling of affected lambs or kids. Udder and teat lesions appear to be more painful, leading to refusal of the affected dam to nurse her offspring. This feeding hiatus in turn may result in neonatal starvation. Lesions also have been reported on the ears, face, periorbital region, poll, scrotum, perianal region, and distal extremities. Rare cases of body (trunk and flanks) lesions have been reported in both sheep and goats.6,7 More severe forms, described as malignant, persistent, or chronic, have been reported. In rare cases, extension of lesions down the respiratory tract may predispose the affected animal to pneumonia, and extension down the alimentary tract may lead to gastroenteritis. A mortality rate of 10% was reported among 550 5-month-old lambs, in which severe facial edema and extensive proliferative necrotic lesions developed in the anterior two thirds of the buccal cavity, including the tongue.8 The stress of transportation may have increased the clinical severity of the disease in the aforementioned report.

Treatment

Treatment of contagious ecthyma is seldom attempted because the disease is self-limiting and should resolve within 3 weeks. At that time, the scab will fall off, thereby contaminating the environment. The disease is of little clinical consequence in weaned and older animals, but neonates may need supplemental feedings. Secondary bacterial infection may occur and if suspected can be treated with topical or systemic antibiotics (see Appendix 1). In some parts of the world, blowfly strike can complicate contagious ecthyma, so affected animals should be observed for this disease and treatment instituted as necessary. Animals with greater economic or sentimental value in which the disease results in anorexia secondary to painful oral lesions may be treated with electrocautery and débridement after spray cryotherapy, with good results.9 Use of ointments and astringent lotions may actually delay healing.10

Prevention

Once the disease is on the farm, vaccines are available that can help in its control. Vaccines are live and should not be used unless the disease is known to be present in a herd or flock. Most commercial vaccines are labeled for sheep but not goats. Although use of these vaccines in goats has at times appeared anecdotally efficacious, research has indicated that sheep vaccines were not effective in protecting goats from the wild-type contagious ecthyma virus found in goats.11 More recently, a goat strain vaccine for contagious ecthyma was found to be protective against experimental challenge.12

Vaccines typically are placed on scarified skin of the medial thigh. Other sites should be used, such as inside the ear pinna or under the tail, for vaccinating lactating females. Formation of scabs should occur by 3 to 4 days if the vaccination is successful. If vaccination is used, its use should be tailored to optimal management for a particular herd or flock. One approach to vaccine use is to begin with vaccination of all animals that have not been previously exposed and then vaccinate only new naive stock (from new births and new additions) annually. Immunity is reported to be acquired by 3 weeks after vaccination but is not considered to be lifelong.13 Naturally exposed animals that have recovered usually are solidly immune for 2 to 3 years.10 It has been stated that colostrum immunity does not occur, because antibodies do not appear to be passed in the colostrum.1,10 A study by Perez, however, demonstrated that lesions did not develop in kids of vaccinated does when challenged before 45 days of age, whereas lesions did appear in kids older than 45 days of age.14 On some farms in which the disease is endemic, producers may choose to simply live with the disease. The disease has a shorter course and is less severe in reinfected animals.

Sheep Pox and Goat Pox

The agents of sheep pox and goat pox are closely related viruses of the Capripox genus in the family Poxviridae. Although the viruses tend to be species-specific, cross-species infection has been reported. Mortality is low in endemic regions but may be high when naive sheep or goats are exposed. Transmission (thought to occur by aerosol and contact with lesions) increases with close contact with infected herds or flocks. These diseases currently are endemic in northern Africa, the Middle East, and southeastern Asia, with occasional outbreaks in southeastern Europe. One case of goat pox in the United States has been reported,16 but a U.S. Department of Agriculture–Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) website states that neither disease has occurred in the United States. Contagious ecthyma is the primary consideration in the differential diagnosis for sheep pox and goat pox. However, sheep and goat pox lesions tend to occur over the entire skin surface. The two viral agents (of contagious ecthyma and of sheep or goat pox) are easily differentiated by electron microscopy. A recent review of sheep pox has been published.17

Scrapie

A discussion of scrapie is beyond the scope of this chapter (see Chapter 13). As a consequence of the intense associated pruritus, however, scrapie-infected sheep or goats (although pruritus is much less common in goats than in sheep) may present with hair or wool loss secondary to mechanical excoriation. Scrapie does not directly affect the skin; skin lesions are simply a result of the intense pruritus and subsequent aggressive scratching.

Bluetongue

A discussion of bluetongue is beyond the scope of this chapter (see Chapters 4 and 14). However, skin lesions suggestive of bluetongue include coronitis, ulcerations of the oral mucosa, and muzzle edema. Goats are relatively resistant to clinical bluetongue.

Vesicular Stomatitis

Sheep and goats never show clinical signs of vesicular stomatitis.18 A 1995 outbreak of the disease in the western United States did not identify a single sheep or goat seropositive for the virus.18 Unpublished reports of vesicular stomatitis in goats, however, indicated that vesicles may occur at the commissures of the lips.19

1. Scott D.W. Large animal dermatology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988.

2. Romero-Mercado C.H., et al. Virus particles and antigens in experimental orf scabs. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch. 1973;40:152.

3. Nettleton P.F., et al. Natural transmission of orf virus from clinically normal ewes to orf-naive sheep. Vet Rec. 1996;139:364.

4. de la Concha-Bermejillo A. Orf/contagious ecthyma. In: Haskell S.R.R., editor. Blackwell’s Five-minute veterinary consultant. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

5. McElroy M.C., Bassett H.F. The development of oral lesions in lambs naturally infected with orf virus. Vet J. 2007;174:663.

6. Coates J.W., Hoff S. Contagious ecthyma: an unusual distribution of lesions in goats. Can Vet J. 1990;31:209.

7. Sargison N.D., Scott P.R., Rhind S.M. Unusual outbreak of orf affecting the body of sheep associated with plunge dipping. Vet Rec. 2007;160:372.

8. Gumbrell R.C., McGregor D.A. Outbreak of severe fatal orf in lambs. Vet Rec. 1997;141:150.

9. Meynink S.E., Jackson P.G.G., Platt D. Treatment of intraoral orf lesions in lambs using diathermy and cryosurgery. Vet Rec. 1987;121:594.

10. Blood D.C., Radostits O.M., Henderson J.A., et al. Veterinary medicine. London: Baillière Tindall; 1983.

11. de la Concha-Bermejillo A, Ermel RW, Zhang MZ: Contagious ecthyma (ORF) virulence factors and vaccine failure, Proceedings of the One Hundred and Third Annual Meeting of the United States Animal Health Association, San Diego, Calif, 1999.

12. Musser J.M.B., et al. Development of a contagious ecthyma vaccine for goats. Am J Vet Res. 2008;69:1366.

13. Mullowney P.C. Skin diseases of sheep. Vet Clin North Am Large Anim Pract 6. 1984:131.

14. Perez JLT: Kids immunity to contagious ecthyma (orf virus), presented at the Goat Diseases and Production 2nd International Colloquium, Niort, France, June 26 to 29, 1989 (Abstract p 24).

15. Renshaw H.W., Dodd A.G. Serologic and cross-immunity studies with contagious ecthyma and goat pox virus isolates from the western United States. Arch Virol. 1978;56:201.

16. Animal Health Monitoring and Surveillance: Status of reportable diseases in the United States, USDA-APHIS (website): http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/nahss/disease_status.htm#sheep, Accessed November 12, 2008.

17. Bhanuprakash V., et al. The current status of sheep pox disease. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;29:27.

18. Kitching P. Notifiable viral diseases and spongiform encephalopathies of cattle, sheep and goats. In Practice. 1997;19:51.

19. Bridges V.E., et al. Review of the 1995 vesicular stomatitis outbreak in the western United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1997;211:556.

20. Smith M.C., Sherman D.M. Skin. Goat medicine, ed 2. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Bacterial Diseases

Dermatophilosis (Streptothricosis, Lumpy Wool Disease, Rain Scald, Rain Rot)

Dermatophilosis (streptothricosis, lumpy wool disease, rain scald, rain rot) is a disease of all ruminants caused by the gram-positive filamentous bacterium Dermatophilus congolensis. This bacterium appears to be maintained within herds or flocks by carrier animals. The organism is considered an obligate parasite of ruminant skin and was not thought to survive for very long in the soil, but later research indicates that it may survive for several months, especially within cast-off crusts.1,2 Predisposing factors for clinical disease include skin damage (as from biting insects or physical abrasion), excessive moisture (hence the common name “rain rot”), and concurrent diseases and stresses that compromise the host immune system. The loss of the sebaceous film layer on skin is thought to predispose the animal to development of the disease. Excessively rainy conditions without appropriate shelter can lead to dilution of this sebaceous layer, thereby increasing the chance of clinical disease.

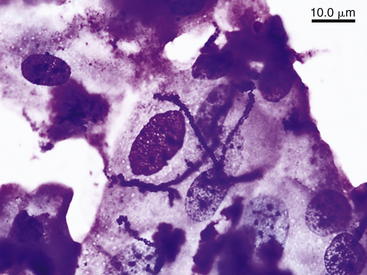

The incubation period averages 2 weeks. The infective form of the organism is the motile zoospore (Figure 10-2), which germinates, penetrates the epidermis, and invades hair or wool follicles. Neutrophils migrate to the affected areas, resulting in accumulation of a serous exudate that seeps to the epidermal surface. The older epidermal skin deteriorates while a new layer of epidermis forms below. This new layer also becomes infected with hyphal branches. Eventually, thick scabs are formed. Early clinical manifestations include small, raised, and circumscribed crusts of epidermal cells and serous exudates with embedded hairs or wool. The disease follows a similar pattern in sheep, but the serous exudates may not be adherent to the epidermis. It also is responsible for “strawberry footrot” of sheep, which appears as dry scabs on the lower legs. Removal of the dry scabs leaves a mass of granulation tissue that has the appearance of a strawberry (hence the name). Although it can be spread from acutely infected animals, outbreaks are rare but have been reported.3 Young goats appear to be more susceptible than adults to development of clinical disease.3,4 Likewise, young sheep are more susceptible than adult sheep.5

Clinical Signs

Follicular and nonfollicular papules and pustules develop and rapidly coalesce and rupture, with consequent matting of groups of hairs or clumps of wool. These are classically described as “paintbrush lesions” in haired ruminants. Lesions may be painful but are not pruritic. In sheep, crusts occurring at the coronary band (i.e., strawberry footrot) also may extend to the carpi or tarsi. Lesions also may be present on other parts of the body. In goat kids, lesions tend to be on the ears and tails; in adults, lesions tend to be on the muzzle, in the dorsal midline, or on the scrotum or distal legs.4 Lesions have been reported in the ears of kids at 5 days of age.6 Although the condition is relatively rare, it may be fatal in livestock debilitated by other diseases and poor nutrition.

Diagnosis

Staining (Gram stain or methylene blue) of direct smears of lesions should reveal branching hyphae with cuboidal packets of coccoid cells arranged in parallel rows (resembling railroad tracks) within the filaments (see Figure 10-2). Skin biopsy and histopathologic examination also may be helpful. Culture can be confirmatory, although possible subsequent infestation by other bacterial and fungal organisms may complicate the diagnosis in chronic cases.7

Treatment

Agents for topical treatment include iodophors, 2% to 5% lime sulfur, 0.2% copper sulfate, 0.5% zinc sulfate, and 1% potassium aluminum sulfate. These agents may be applied as total body washes, sprays, or dips for 3 to 5 consecutive days and then weekly until healing has occurred. Systemic antibiotics such as procaine penicillin G (5000-10000 IU/kg twice a day for 4 to 5 days), oxytetracycline (one or two doses of 20 mg/kg during a 72-hour interval), or ceftiofur (2 ml/100 lb once daily for 4 to 5 days) may be effective. The organism is reported to be resistant to polymyxin B, bacitracin, and sulfonamides. Lesions in kids tend to heal without treatment within 2 to 3 months.8 Dermatophilus is potentially zoonotic to humans.

Prevention

In areas in which the disease is prevalent, removal and disposal of crusts, keeping stock dry (providing shelter from wet weather), providing good-quality nutrition, and control of ectoparasites may limit the number of clinical cases. Vaccines have been studied but do not appear to offer significant protection.5

Fleece Rot (Water Rot, Weather Stain)

Fleece rot is an exudative bacterial dermatitis of sheep that is characterized by a greenish-discolored, matted wool. This disease reduces the quality of the wool but is most important as a predisposing factor for fly strike. Although other fleece bacteria may play a significant role in the disease, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is considered the primary etiologic agent.9 The disease was first recognized in Australia in the latter part of the 1800s.5 Bacteria cultured from the skin of affected sheep, when applied to unaffected sheep, resulted in the disease.10

The necessity of moisture for development of disease symptoms was noted in 1929 by Seddon and McGrath.11 Both wool traits and body conformation traits are predisposing factors for fleece rot in sheep, and this susceptibility is reportedly heritable.11 The disease appears to be most prevalent in Australia, with reported prevalence rates averaging 24%.5 The disease does not appear to be of clinical or economic significance in the United States but has been reported.12 The reason for the increased susceptibility of young sheep compared with older stock is not known, but causative or contributing factors may include maturity of wool and skin characteristics and development of a certain level of immunity after exposure.5 Fleece rot predisposes affected sheep to blowfly strike.

Clinical Signs

The most characteristic clinical sign is the greenish discoloration of wool. A copious serous exudate also may be evident and probably is the attraction for flying insects that leads to associated fly strike. The inflammatory reaction can result in a grayish matted wool. Pruritus also has been reported, but not all affected sheep demonstrate evidence of this symptom.13 Lesions are most common on the back and withers.

Diagnosis

Culture of samples from involved skin and wool is the definitive method to diagnose fleece rot (and would be especially definitive for greenish-discolored wool). Pseudomonas aeruginosa may be found in pure culture. It produces the green pigment pyocyanin.14 Fleece rot may be distinguished from dermatophilosis in that no scab formation is associated with the former.

Treatment

Antibiotics may be helpful, but studies have shown P. aeruginosa to be quite resistant to many antibiotics.15,16 In clinical practice, shearing to allow the involved skin to dry is the most effective means of treatment.

Prevention

Vaccines are under development, but efficacy to date has been disappointing.5 Some prevention is afforded by producing more resistant sheep by breeding for characteristics of wool and body conformation that are less predisposing to the condition. Perhaps the most practicable control measure is to shear the sheep before the onset of the rainy season.

Malignant Edema (Swelled Head, Bighead)

Malignant edema, also called “swelled head” or “bighead,” is a rapidly fatal disease caused by clostridial species, most commonly Clostridium sordellii, Clostridium novyi, Clostridium septicum, and Clostridium chauvoei, and is seen most commonly in young rams. Although swelled head of bucks (goats) is mentioned in many textbooks, studies or case reports in goats ar lacking. The organisms typically exist as spores in the soil and appear to occur predominantly in moist soils that are rich in organic matter.17 The organisms usually enter the body through breaks in the skin or mucosa. With development of the requisite anaerobic conditions in body tissues, the organisms proliferate and release several exotoxins that react locally and systemically. The spores of clostridial organisms are thought to survive in the environment for several years. The disease is most common in Montana in the United States but also occurs in South Africa, South America, and Australia.18

Clinical Signs

The disease usually is sporadic in nature but can occur as outbreaks. The likely cause of a Brazilian outbreak was use of a single common needle to vaccinate a 1000-head flock of sheep with a commercial clostridial vaccine.17 Several sheep died in that outbreak, all within 1 to 3 days of vaccination. Clinical signs observed before death included severe depression, swelling around the vaccination site, lameness, subcutaneous edema, and crepitation.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree