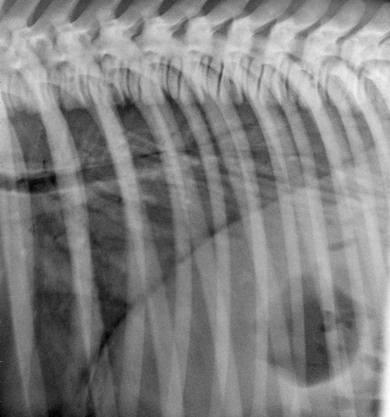

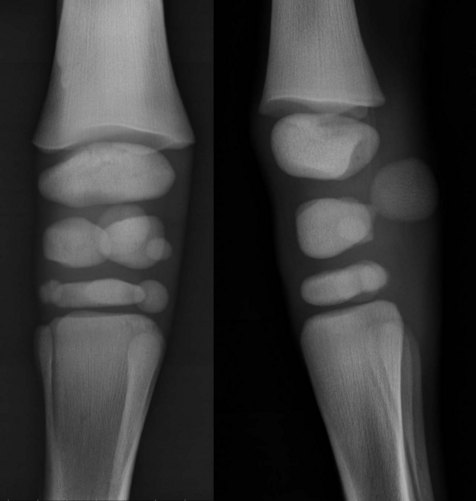

Chapter 20 20.2 Systemic diseases involving multiple body systems 20.3 Diseases of the cardiovascular system 20.4 Diseases of the respiratory system Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) Idiopathic tachypnoea and hyperthermia Upper respiratory tract (URT) disease 20.5 Diseases of the nervous system 20.7 Diseases of the alimentary system 20.9 Diseases of the urogenital system 20.10 Endocrine/metabolic disorders 20.11 Haemolymphatic and immunological disorders Failure of transfer of passive immunity (FTPI) Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) Neonatal isoerythrolysis (isoimmune or alloimmune haemolytic anaemia) 20.12 Miscellaneous conditions 1. Prematurity: foal less than 320 days’ gestation. 2. Dysmaturity: signs of immaturity/prematurity in foals more than 320 days’ gestation. Commonly low birth weight, despite normal gestational age. 3. Postmaturity: foal greater than 360 days’ gestation. Normal to large axial skeletal size, but thin/emaciated. Clinical characteristics of prematurity: Pathophysiology and diagnostic findings: 1. Immature adrenal cortical function: • Low cortisol concentrations. • Poor response to adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). • Neutropenia, lymphocytosis, decreased neutrophil:lymphocyte ratios. 3. Poor vascular tone and responsiveness; hypotension is common. 4. Immature renal function, low urine output. • Increased chest wall compliance. • Thoracic radiographs: a diffuse, ‘ground glass’ appearance is seen with surfactant deficiency (Figure 20.1). 6. Gastrointestinal immaturity: unable to handle oral diet; poor absorption of colostrum. 7. Musculoskeletal immaturity: lack of cuboidal bone ossification seen on carpal and tarsal radiographs (Figure 20.2). Figure 20.2 Radiographs of a premature foal (310 days) showing incomplete ossification of carpal cuboidal bones. Treatment (see Chapter 26): The treatment of premature foals remains one of the most challenging problems presented to the equine practitioner. 1. Supportive care is of primary importance: • Maintain sternal recumbency. • Intranasal oxygen if hypoxaemic. • Mechanical ventilation may be needed. 3. Cardiovascular support if necessary: • Enteral nutrition if gastrointestinal function is mature. • Parenteral nutrition if gastrointestinal function is immature or dysfunctional. 5. Adrenocortical axis support: corticosteroids may be used if adrenal insufficiency is suspected. • Bandages, splints, braces, etc., as needed for musculoskeletal support. • Exercise should be limited if hypoplasia of the carpal or tarsal bones is present. • Determine adequacy of passive transfer of immunoglobulin. • Administer colostrum or plasma if necessary. 8. Determine the underlying cause of prematurity if possible: • Survival of foals induced before 320 days is poor. • Survival greater than 70% is reported for spontaneous birth between 280 to 322 days’ gestation. • Prognosis is better if cause of prematurity/dysmaturity is in utero infection or placentitis. • Concurrent disease (e.g. sepsis, asphyxia) may reduce the prognosis. • Respiratory immaturity is often the limiting factor to survival. • The prognosis is guarded if the neonate does not develop a righting reflex or suckle reflex. Prevention: Prevention is based upon good management practices and on identification of maternal problems that may influence foetal viability and/or the onset of parturition. 1. Identification and treatment of placental infections. Treatment may include antimicrobials, anti-inflammatory drugs, and progesterone. 2. Avoid induction of parturition unless necessary, as readiness for birth is very difficult to predict. 3. Corticosteroids have been successfully used in humans and sheep to encourage foetal maturation. They have not been shown to be effective in the mare. 4. Monitoring foetal heart rate can give an indication of foetal well-being. 5. To prevent postmaturity, remove mares from endophyte-infected fescue pasture or administer dopamine receptor antagonists. 1. Although sepsis can also be secondary to viral or fungal infection, the term sepsis in the foal generally refers to systemic spread of bacteria through the bloodstream. Infection may arise in utero or postnatally. 2. Failure of transfer of passive immunity (FTPI) may predispose to infection (see Section 20.11). 3. Other risk factors include poor hygiene, maternal illness, prematurity, and immunosuppression. 4. Infections are generally a result of opportunistic organisms from the foal’s environment, skin, or the mare’s genital tract. 5. Portals of entry into the body include the respiratory tract, umbilicus, gastrointestinal tract, and placenta. 6. Gram-negative infections predominate. The most common organisms vary with the geographical location. Commonly encountered bacteria include: 7. Gram-positive infections are common, but less frequent than Gram-negative infections. Commonly encountered bacteria include: 1. Early signs are non-specific and include depression, weakness and decreased suckling. 2. Fever, hypothermia, or normothermia may be present, depending on the severity and stage of the disease. 3. Localizing signs of infection: uveitis, hypopyon, pneumonia, enteritis, meningitis, omphalophlebitis, septic arthritis, and osteomyelitis. 4. Injection, petechiation or ecchymotic haemorrhages on the mucous membranes. Subclinical coagulopathy is common. 5. Severe cardiovascular collapse (shock, stupor, coma), with associated tachypnoea, tachycardia, and hypotension. Bradycardia may be present in the late stages of septic shock. 1. Blood culture. A positive blood culture is definitive, but a negative culture does not rule out sepsis; periods of bacteraemia may be intermittent and brief. 2. Culture of other body fluids may be beneficial, e.g. transtracheal aspirates, cerebrospinal fluid, faeces, urine, and synovial fluid. 3. History (risk factors) that may predispose to sepsis includes placentitis or vulvar discharge in the mare, maternal problems during gestation, dystocia, low birth weight, and prematurity. 4. Clinical findings: foals with early disease may present with few and subtle signs; advanced disease may progress to shock and coma. 5. Complete blood count (haematology): • Leucopenia (neutropenia) is common. • White cell count may be normal early in the disease. • Differential cell counts may be more useful than total cell count, e.g. relative neutropenia or neutrophilia, presence of band forms and toxic changes. 7. Sepsis score includes historical, clinical, and clinicopathological information. 1. Antibiotic therapy should be initiated as soon as possible. It is often prudent to suspect sepsis until proven otherwise. • The initial choice of antibiotics should be broad spectrum with an emphasis on the Gram-negative spectrum. • Changes in therapy can be made when and if culture and sensitivity results are available. • Therapy should be long-term in an attempt to prevent localization of infection (secondary complications). 2. FTPI should be treated with immunoglobulin therapy (plasma). 3. Supportive care (see Chapter 26): • Regulate environmental temperature (provide heat source). • Nutritional support; hypoglycaemia is often present; glycogen and fat stores are poor in the foal. 4. Address any underlying infections. • Decrease in systemic vascular resistance resulting from maldistribution of vascular volume. • Secondary to sepsis (septic shock), infection, strangulating intestinal lesions, anaphylaxis. 1. Fluid administration is the single most important treatment for hypovolaemic and distributive shock. • The goal of fluid therapy is to optimize the vascular volume and restore circulatory function and tissue perfusion. • The most appropriate fluid choice is balanced electrolyte solution containing acetate or lactate (e.g. lactated Ringers solution, Hartmann’s solution, Plasma-Lyte 148). • Polyionic fluids remain effective in restoring vascular volume if the PCV remains greater than 20% and the total protein greater than 35 g/L. 2. Hypertonic solutions cause rapid, transient volume expansion; however, hypertonic saline solution is not recommended, as neonatal foals are unable to handle large amounts of sodium. 3. Colloid fluids (Hetastarch or plasma) may be needed in cases of low colloid oncotic pressure. 4. The rate of administration of fluids is variable; crystalloid fluids may be given in boluses of 20 mL/kg, the boluses being repeated if needed after clinical reassessment. 5. In severe cases as much as 90 mL/kg may need to be administered rapidly. 6. Inotropes and vasopressors may be needed if the foal does not respond to fluid therapy: • Dobutamine can be used to increase cardiac output. • Norepinephrine can be used to increase systemic vascular resistance and increase stroke volume. 8. In haemorrhagic shock, whole-blood replacement may be necessary if adequate response is not achieved with crystalloids only. 9. Intranasal oxygen if hypoxaemic shock exists. Mechanical ventilation may be needed in cases of severe pulmonary disease. This is a mutifactorial problem that develops secondary to impairment of tissue oxygen delivery. It is most commonly seen in the neonate shortly after birth when oxygen delivery to the tissues is interrupted (see ‘maladjustment syndrome’ in section 20.5 of this chapter). Pathophysiology: Two major mechanisms may result in cellular deprivation of oxygen, namely, ischaemia and hypoxaemia. Ischaemia (lack of blood flow) is generally more severe than hypoxaemia, because during hypoxaemia some blood flow and oxygen delivery persist. With a lack of blood flow, anaerobic metabolites are not removed from the tissues which may result in severe local and/or cellular acidosis. • Central nervous system: encephalopathy associated with cerebral necrosis, oedema and haemorrhage, although consistent cerebral abnormalities have not been reported. • Renal: acute tubular necrosis. • Gastrointestinal ischaemic necrosis; necrotizing enterocolitis. • Cardiovascular and respiratory systems are less commonly affected. Clinical signs: Signs range from mild depression/transient behavioural abnormalities to severe seizures and generalized organ failure. Many foals do not show obvious clinical signs until 12–24 hours of age. Disorientation, loss of suckle, and tongue protrusion are common physical exam findings. 2. Breathing: if the foal is not breathing or if breaths are infrequent or shallow, provide mechanical ventilation with an endotracheal tube or mask (endotracheal tube is preferable). 3. Cardiovascular support and correction of metabolic disturbances (see previous section on the treatment of shock). 1. Immediately after delivery the heart rate is 60–80 beats/min, increasing to 120–150 within hours to stabilize at 80–100 in the first week of life. 2. Sinus dysrhythmias are frequently found on auscultation and ECG in the immediate postpartum period, probably as a result of increased parasympathetic tone and myocardial hypoxia. Physiological (functional) murmurs are typically crescendo/decrescendo in time (grade 1–3/6), with maximal intensity over the semilunar valves. 3. Other dysrhythmias (ventricular premature contractions, ventricular tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia) are occasionally auscultated immediately after delivery, but they disappear within 15–30 minutes postpartum. 4. To determine the clinical significance of any dysrhythmia, consideration should be given to the clinical, metabolic and haemodynamic status of the foal. 1. Because of the foal’s thin chest, the apex beat is quite prominent, and heart sounds and flow murmurs are louder than in the adult horse. Murmurs are frequent in newborn foals, and in general are not pathological (i.e. functional). In the immediate postpartum period (15 min) most foals have a continuous murmur from blood shunting through the ductus arterious. This represents a transition from the intrauterine fetal circulation in which there is pulmonary hypertension, to an extrauterine circulation in which there is a decrease in vascular resistance from alveoli opening and prostaglandin release. 2. Murmurs are often heard in newborn foals but are not considered pathological unless they persist beyond 4 days of age. Holosystolic ejection-type murmurs are not uncommon and most of the time are physiological (innocent flow murmurs), rather than due to a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). 3. Innocent murmurs may acquire unusual tones if the foal is in lateral recumbency, or is haemodynamically compromised. 4. Functional closure of the ductus arteriosus occurs shortly after birth in most foals. 5. Murmurs that persist after the first week of age should be further investigated. Likewise, murmurs associated with cyanosis should be evaluated immediately. Acquired cardiac defects are uncommon in the foal. Inflammatory or degenerative changes may be identified at necropsy. See Chapter 7 for more detailed descriptions. In foals, myocardial disease is associated with ischaemia, hypoxia, septicaemia, metabolic diseases, nutritional deficiencies (white muscle disease), and respiratory diseases. In white muscle disease (vitamin E and selenium deficiency – see Chapter 21), in addition to muscle weakness, dysphagia, and respiratory dysfunction, some foals may develop a dilated cardiomyopathy. The role of viral infections in myocardial disease is unclear. The clinical presentation of myocardial dysfunction is variable but includes murmurs from valvular incompetency, arrhythmias, atrial and ventricular premature depolarization, exercise intolerance, congestive heart failure, and sudden death. Arrhythmias are a common manifestation of myocardial disease. Diagnostics should include electrocardiography, echocardiography, assessment of serum electrolytes, creatine kinase activity (MB isoenzyme if possible), lactate dehydrogenase, and measurement of cardiac troponin I concentrations. If there is dysphagia or muscle weakness, measurement of vitamin E and selenium should be considered. Myoglobin can be present in urine if there is severe myocardial necrosis. Respiratory rate: Respiration should begin immediately after birth. The respiratory rate of the neonatal foal is approximately 60–80 breaths/minute in the immediate neonatal period, and declines to 30–40 breaths/minute within 1–2 hours after birth. Palpation: Palpation of the thorax should be performed to determine whether fractured ribs are present. One must be careful when assessing fractured ribs as pulmonary damage (pneumothorax, haemothorax) and cardiac damage can be induced. Most fractures are in ribs 3–6, and crepitus or a clicking noise can be heard on auscultation. Thoracic auscultation: Thoracic auscultation is not as reliable an indicator of lower respiratory disease in the neonate as in adults, because often only subtle changes in lung sounds are appreciable on auscultation, even in the presence of very severe pulmonary disease. An elevation of respiratory rate, increased effort, and abnormalities of breathing pattern (nostril flaring, an abdominal component to the respiratory pattern, respiratory stridor) are more appreciable than auscultatory changes in foals with respiratory disease. Lung sounds: Lung auscultation in the period immediately postpartum reveals crackles as airflow increases in a fluid-filled environment. Arterial blood gas analysis: Arterial blood gas analysis aids in the characterization of the cause of lower respiratory disorders and cardiovascular disease and assists in the most appropriate course of therapy as well as response to treatment. Radiography: Radiography provides a good diagnostic method to assess the type and extent of pulmonary disease. Evidence of pulmonary disease in the immediate postpartum period indicates in utero infections, septicaemia, peripartum stress (meconium aspiration), or prematurity. 1. Bacterial pneumonias may be characterized by alveolar, bronchoalveolar, and/or interstitial patterns. There is not a pathognomonic radiographic pattern produced by viral diseases, although in adult horses often an interstitial pattern is typical. 2. Ventral distribution of pathological changes may be indicative of bacterial or aspiration pneumonia (bacterial, meconium, milk). If there evidence of aspiration pneumonia, a complete evaluation of the mouth (cleft palate) and upper airways is indicated. 3. A ‘cotton ball or nodular’ pattern in the mid to dorsal thorax in young foals suggests fungal pneumonia. In older foals (>3 months) this pattern can be consistent with interstitial pneumonia. Foals with interstitial pneumonia can also have a miliary interstitial pattern. 4. Premature or dysmature foals with evidence of pulmonary disease may have pulmonary atelectasis (“ground-glass” appearance), indicating decreased surfactant production and/or bacterial infection. Ultrasonography: Thoracic ultrasonography has become a routine diagnostic method in foals with evidence of respiratory diseases (respiratory distress, diaphragmatic hernias, haemothorax) and systemic diseases (fever, sepsis). 1. In the foal with pulmonary disease it is preferable to perform ultrasonography with the foal in sternal recumbency or standing. This is particularly important for conditions such as diaphragmatic hernia, haemothorax, and pleural effusion. 2. Rib fractures can be identified as disruptions of the cortical surfaces of the rib, above but not involving the costochondral junction. Hypoechoic regions in the adjacent lung surface indicate pulmonary trauma. Homogeneous, slightly echogenic (cellular) fluid within the thorax is consistent with haemothorax. Pleural effusion is variable, from hypoechoic fluid when cellularity is low, to a hyperechoic fluid that can be homogeneous or filled with cellular debris and fibrin. The presence of gas echoes (hyperechoic) in the pleural fluid indicates either a pulmonary laceration (haemothorax) or a pleuritis/pleuropneumonia with involvement of anaerobic microorganisms. 3. Ultrasonography, like radiography, is not specific in the identification of pulmonary parenchymal disease. Thoracic ultrasonography in young foals with pulmonary disease, regardless of the aetiology, often reveals non-specific findings. Artefacts such as ‘comet tails’ from excessive reverberation indicate roughening of the pleural surfaces. Cavitary lesions (abscesses) and pulmonary consolidation are often identified by ultrasound. • The goal is to identify the aetiological agent and its antimicrobial sensitivity. • Cytology can help differentiate the type of inflammatory response. • The previous use of antimicrobial drugs decreases the success of a positive culture. • Common sense should be used: in foals with severe pulmonary disease performing a transtracheal aspirate may be contraindicated. Endoscopy: Endoscopy is indicated in upper-airway disease (obstruction, laryngeal dysfunction, guttural pouch disease) and malformations (cleft palate, laryngeal and tracheal malformation). Lung biopsy: Percutaneous lung biopsy can be considered in conditions in which there is evidence of pulmonary parenchymal disease but routine diagnostic tests are negative. This is not a procedure routinely performed in young foals as its indications include pulmonary neoplasia and fungal pneumonia. Do not perform in foals with tachypnoea or evidence of poor ventilation, or in foals with infectious pulmonary disease. Haemothorax and epistaxis can develop after lung biopsy. • Surfactant is critical for alveolar function. In foals, surfactant production begins at 100–150 days of gestation, being complete in most foals by 290–310 days of gestation, but in some foals it may not be complete until delivery. This process is variable, and gestational age should not be used as an indicator of pulmonary maturation. Foals with normal gestation length and evidence of incomplete organ maturation (respiratory, musculoskeletal) are considered dysmature. • Alveolar collapse and subsequent respiratory distress occur from the absence of surfactant. • Additional complicating factors in premature/dysmature foals with pulmonary disease include excessive compliance of the chest wall with poor compliance of the lung parenchyma, making the foal work harder during inspiration, which can lead to diaphragmatic fatigue. 2. Decreased respiratory efficiency. • Factors that lead to increased demand or fatigue. • Failure to establish functional residual capacity shortly after birth. • Increased vascular permeability, decreased surfactant, and oedema. • Cardiac anomalies (VSD, PDA, tricuspid valve atresia). • Gastrointestinal tympany (enteritis, meconium impaction), diaphragmatic hernia. • Is not unusual for premature/dysmature foals or foals with peripartum hypoxia to have a decreased respiratory rate and abnormal breathing patterns. 3. Dystocia or other problems at or during foaling: premature placental separation, umbilical cord compression, fractured ribs, prolonged parturition, perinatal hypoxia. 4. Any condition that results in prolonged recumbency and atelectasis. • Oxygen therapy alone is often not sufficient, and mechanical ventilation may be necessary. • Cardiovascular support and correction of metabolic disorders. • Treatment of the underlying condition and surfactant replacement in premature foals. • Glucocorticoid replacement therapy (hydrocortisone, dexamethasone) – with the rationale of increasing surfactant production – should be considered. • Under physiological conditions meconium is not evacuated before birth. In utero, asphyxia, foetal stress, or mechanical factors during delivery may result meconium release into the amniotic fluid. • Deep gasping or failure of protective mechanisms can result in aspiration. • Meconium obstructs airways, resulting in air trapping and atelectasis, mechanical irritation, and chemical bronchopneumonia. • Other causes of respiratory disease must be ruled out via a complete respiratory evaluation. All other values should be within normal limits. • Respiratory and systemic infections or pain must be ruled out. • Haematology, fibrinogen concentrations, and serum chemistry may aid in the diagnosis as in most cases, except for an increase in haematocrit and a stress leukogram, these are normal. • Metabolic acidosis and other causes of tachypnoea must be ruled out. Aetiology: There is right-to-left shunting through the foramen ovale and/or the ductus arteriosus, hypoxaemia, hypercapnia, and pulmonary hypertension. In neonates, pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, and pulmonary blood flow increases during and immediately after delivery. As gas exchange increases, pulmonary blood pressure decreases; however, a failure in the mechanisms that regulate the decrease in pulmonary blood pressure leads to hypertension. Reversal to foetal circulation can occur with intrauterine foetal diseases, premature placental separation, prematurity/dysmaturity, peripartum asphyxia, respiratory distress syndrome, meconium aspiration, severe sepsis, and pneumonia. Clinical signs: There is a tachypnoea, nasal flaring in severe cases, and tachycardia with systolic murmurs of variable degrees. Cyanosis may be present. Diagnosis: Clinical findings include respiratory acidosis, hypoxaemia, and hypercapnia. On echocardiography a persistent foramen ovale or PDA, with pulmonary artery dilation (with or without right ventricular hypertrophy), is a consistent finding of pulmonary hypertension. Treatment: Treatment includes oxygen insufflation, correction of the respiratory acidosis, and mechanical ventilation in severe cases. Other treatments that have been proposed or used include vasodilators (prostacyclin, nitric oxide) and bronchodilators. Bronchodilators are controversial as they can induce ventilation/perfusion mismatch, worsening the clinical signs. There are many causes of upper airway obstruction in the foal. However, the prevalence is low. Many obstructions of the URT are partial and may go unnoticed until the foal is exercised. A more thorough discussion of URT disease is found in Chapter 5. • Foals may be born normal and show acute onset of respiratory disease in the first days of life. A number of foals are born sick, weak, dysmature, depressed, with tachypnoea or respiratory distress. • The virus infects other systems, and signs of gastrointestinal disease (diarrhoea) and liver disease (icterus) may be present. Leukopenia with lymphopenia is common from lymphoid tissue necrosis. • Secondary bacterial infections are frequent in foals that live for a few days. • Clinical history and findings. It can present as a single sick foal, as an outbreak of sick foals, abortions, or horses with respiratory disease. • Virus isolation (inconsistent). • Serology, using paired samples. This may not be practical as most foals die within days. Serology should be performed in the dam and other horses in the premises. • Polymerase chain reaction (PCR). • Histopathology: inclusion bodies in cells of the respiratory epithelium, liver, intestinal mucosa and adrenal gland; interstitial pneumonia; hypoplasia or necrosis of the thymus/spleen; and hepatic abnormalities. Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry. • Disinfect or dispose of tools and instruments that have been in contact with sick horses. • Isolate sick foals and horses exposed to sick foals. • Follow appropriate isolation protocols. • Vaccinate non-exposed mature horses. • Designate specific personnel to work with pregnant mares to avoid cross-contamination.

Diseases of the foal

20.1 Prematurity/dysmaturity

20.2 Systemic diseases involving multiple body systems

Shock (see Chapter 26)

Classifications

Perinatal asphyxia

Organ dysfunction

20.3 Diseases of the cardiovascular system (see Chapter 7)

Physical examination

Congenital heart disease

Acquired cardiac defects

Myocardial disease

20.4 Diseases of the respiratory system (see Chapter 6)

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)

Meconium aspiration

Idiopathic tachypnoea and hyperthermia

Reversal to foetal circulation

Upper respiratory tract (URT) disease

Viral diseases

Equine herpesvirus 1 (rhinopneumonitis)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Diseases of the foal