Chapter 2 Diseases of the Digestive System

Food is vital for the life of the animal because it provides the source of energy that drives all the chemical reactions in the body. Consumed food is not in a form readily usable by the body. The digestive system breaks down the consumed food to a point where it can be absorbed and used by the animal.

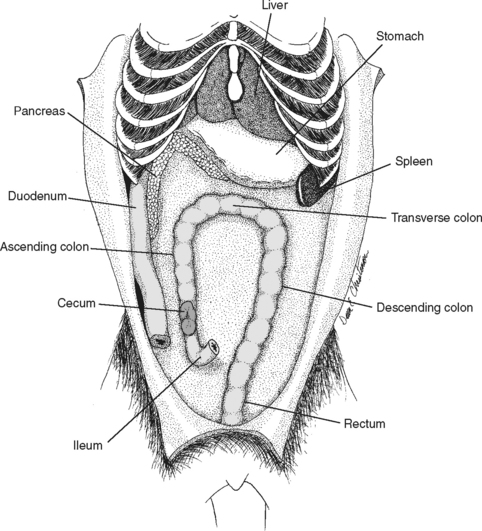

The organs of digestion can be divided into two main groups: the gastrointestinal tract, a continuous tube beginning at the mouth and ending at the anus, and the accessory structures—the teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder (Fig. 2-1).

Figure 2-1 Gastrointestinal system of dog (small intestine has been removed).

(From Christenson DE: Veterinary medical terminology, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders, by permission.)

ORAL DISEASES

Gingivitis/Periodontal Disease

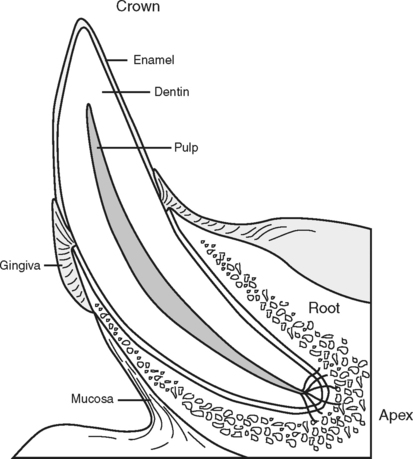

Periodontal disease results from infectious inflammation of the gingiva, and it affects all the structures involved with tooth attachment (Fig. 2-2, see also Color Plate 1). This condition is a continuum of disease beginning with gingivitis and progressing to periodontitis and tooth loss. Gingivitis, a reversible process that involves inflammation of the margins of the gums is caused by accumulation of tartar on the teeth, which acts as a nidus for bacterial multiplication. Enzymes produced by these bacteria damage the tooth attachments and result in inflammation. Without intervention, gingivitis will progress to periodontitis, an irreversible condition resulting in loss of gingival epithelial root attachment and alveolar bone reabsorption. Periodontal disease is estimated to occur in 60% to 80% of dogs and cats.

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal disease is a collective term for plaque-induced inflammation of the gums. This inflammation is progressive and includes gingivitis, gingival hyperplasia, periodontitis with vertical bone destruction, and periodontitis with horizontal bone destruction. The final outcome of periodontal disease is loss of the tooth.

Gingivitis

Gingivitis (inflammation of the gingiva) is the earliest sign of periodontal disease. It results from the buildup of dental plaque (tartar) in the gingival sulcus. Bacteria seldom invade the gingival tissues directly; however, anaerobic bacteria that comprise much of the subgingival plaque secrete enzymes that result in inflammation to the surrounding gum. The inflammatory response of the host animal results in gingival hyperplasia. (Gingival hyperplasia may be breed related or drug induced as well.) As plaque is mineralized, it becomes dental calculus, which protects the bacterial environment.

Oral Trauma

Gunshot wounds often result in dental or other oral injuries, as well as shattered bones, teeth, and penetrating wounds of the tongue. Fishhooks of all types attract both dogs and cats. Hooks can become embedded in the lips or the tongue (sometimes both at the same time), resulting in a frantic animal that may require sedation or general anesthesia to properly remove the hook. Round steak bones present a special challenge. These bones typically become lodged behind the canine teeth, over the end of the mandible. As the tissue swells, it becomes painful. General anesthesia is required in most cases. Bones must be cut in sections for removal. Cats also have problems with bones; flat chicken bones can become lodged across the upper dental arcade, requiring sedation for removal.

Salivary Mucocele

The salivary mucocele is the most common clinically recognized disease of the salivary glands in dogs, although it may also occur in cats secondary to trauma. A mucocele is an accumulation of excessive amounts of saliva in the subcutaneous tissue and the consequent tissue reaction that occurs. This disease occurs most often in dogs between the ages of 2 and 4 years; German shepherds and miniature poodles are most commonly affected. The initial cause of the accumulation usually is unknown. Owners report a history of a slowly enlarging, fluid-filled, nonpainful swelling on the neck. The animal may have respiratory distress or difficulty swallowing secondary to the partial obstruction of the pharynx. In cats, a ranula (a large fluid-filled swelling under the tongue) may be seen.

Oral Neoplasms

Benign neoplasms such as papillomas and epulides are seen in the dog (see Color Plate 8). Papillomas, pale-colored cauliflower-like growths, are viral in cause and may be removed surgically or may regress spontaneously. Epulides occur in the gingiva near the incisor teeth. They are generally slow growing but some may be locally invasive and involve bone destruction.

TREATMENT

ESOPHAGEAL DISEASE

Diseases of the esophagus include megaesophagus (see Chapter 8), esophagitis/gastroesophageal reflux (GER), vascular ring anomalies (see Chapter 1), and foreign body obstruction.

Esophagitis/Gastroesophageal Reflux

TREATMENT

Ingestion of irritant substances

INFORMATION FOR CLIENTS

DISEASES OF THE STOMACH

Gastric motility depends on two motor control centers in the stomach plus external control from the autonomic nervous system. Emptying of solids depends on caloric density and pyloric resistance. The presence of fats and proteins will delay gastric emptying.

Acute Gastritis

TREATMENT

INFORMATION FOR CLIENTS

Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Chronic Gastritis, Enteritis, Colitis)

TREATMENT

INFORMATION FOR CLIENTS

Gastric Ulceration

TREATMENT

Gastric Dilation/Volvulus

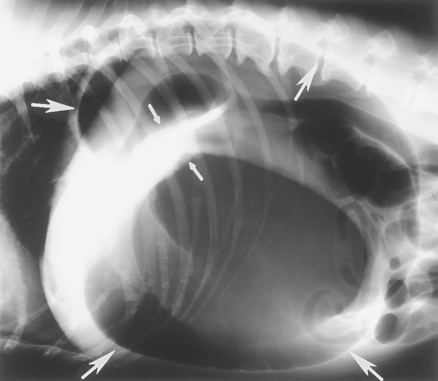

The stomach is similar to a bag with openings at each end. As the stomach fills with air, food, and/or fluid, the outflow tracts can become occluded. Further distension results in simple dilation (an air-filled stomach), or the air-filled stomach may twist along its longitudinal axis (volvulus). The pylorus usually passes under the stomach and comes to rest above the cardia on the left side of the abdomen. The enlarged tympanic stomach pushes against the diaphragm, making breathing difficult and blocking venous return of blood through the hepatic portal vein and the posterior vena cava. The increased luminal pressure within the gastric wall results in ischemia and subsequent necrosis of the wall.

DIAGNOSIS

TREATMENT

Alleviate distention

Continuous monitoring of the electrocardiogram