Chapter 49 Diseases of the Digestive System

NORMAL DIGESTIVE SYSTEM ANATOMY

After digestion by the cecum, the remaining material goes into the large colon. The large colon has four portions: the right and left ventral and dorsal colons. The contents then travel into the transverse and then the descending colons. The main function of the colon is to absorb water from the feedstuff.

DENTAL CONSIDERATIONS: UNEVEN TOOTH WEAR

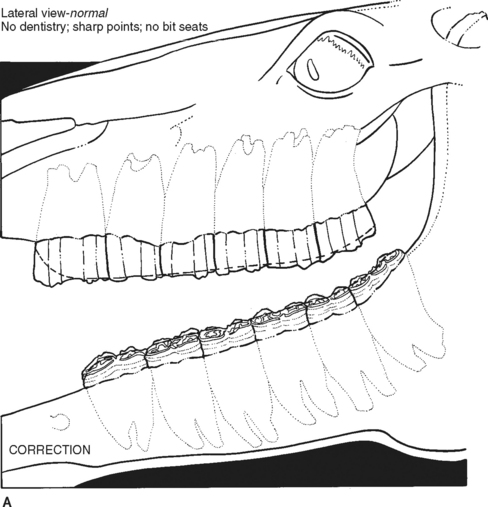

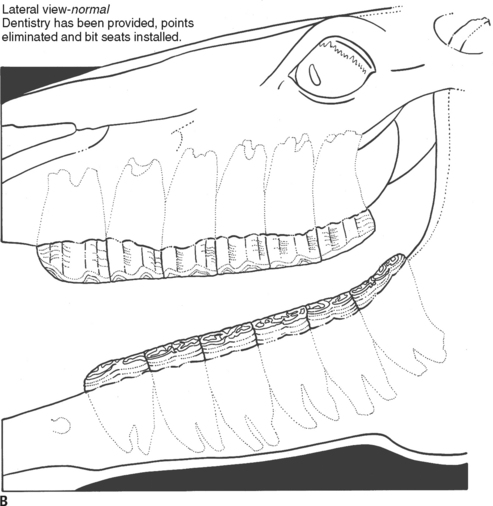

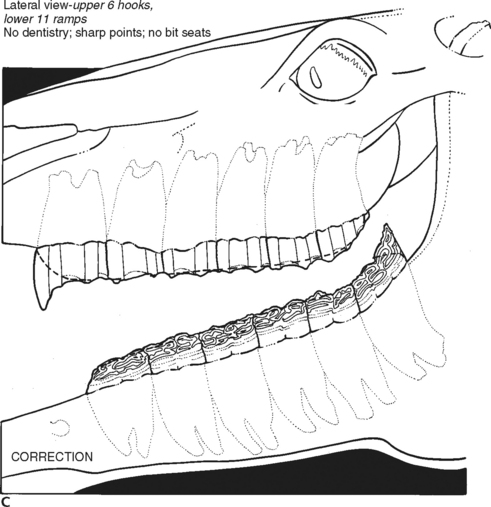

Common dental abnormalities that need attention include (Fig. 49-1):

• Retained wolf teeth that can cause pain to the tongue when it is displaced because of bit pressure

TREATMENT

• If the veterinarian sees any of the above problems on a dental examination, he or she should take steps to correct the problem.

• Hooks, ramps, sharp points, and wave mouths can be corrected by floating the horse’s teeth. Basically, a rasp is passed over the tooth to remove the unwanted sharp portions. Floats can be either hand floats or power floats. Power floats are becoming more commonly used because they are easier on the user.

CHOKE

DIAGNOSIS

• Definitive diagnosis can be obtained by palpation of the esophagus and passage of nasogastric (NG) tube (or lack thereof).

GASTRIC ULCERS

The prevalence of gastric ulcers in horses is mainly due to management techniques. Most heavily worked horses are kept in stalls for 22 or more hours each day. They are fed high-concentrate meals rather than being allowed to graze freely all day. Feeding concentrate meals predisposes a horse to ulcers by two major pathways:

TREATMENT

• Omeprazole has been found to be the most effective pharmaceutical agent for the treatment of gastric ulcers.

INFORMATION FOR CLIENTS

• Performance horses, young horses in training, and stalled horses are most at risk for development of ulcers. Make sure your training program gives the animal plenty of relaxation time, more forage in the diet, and lots of grazing. If you suspect problems, have an endoscopic examination. Ulcers can be healed before they cause problems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree