CHAPTER 2 Diagnostic Methods

The systematic approach

A rational approach to the accurate diagnosis of dermatologic diseases is presented in Table 2-1.

TABLE 2-1 Steps to a Dermatologic Diagnosis

| Major Step | Key Points to Determine or Questions to Answer |

|---|---|

| Chief complaint | Why is the client seeking veterinary care? |

| Signalment | Record the animal’s age, breed, sex, and weight. |

| Dermatologic history | Obtain data about the original lesion’s location, appearance, onset, and rate of progression. Also determine the degree of pruritus, contagion to other animals or people, and possible seasonal incidence. |

| Previous medical history | Medical history that does not directly seem to relate should also be reviewed. |

| Client credibility | Determine what the clients initially noticed that indicated a problem. Repeat questions and ask in a different way to determine how certain the clients are and whether they understand the questions. |

| Physical examination | Determine the distribution pattern and the regional location of lesions. Certain patterns are diagnostically significant. |

| Closely examine the skin to identify primary and secondary lesions. | |

| Determine skin and hair quality (e.g., thin, thick, turgid, elastic, dull, oily, or dry). | |

| Observe the configurations of specific skin lesions and their relationship to each other. | |

| Differential diagnosis | Differential diagnosis is developed on the basis of the preceding data. The most likely diagnoses are recorded in order of probability. |

| Diagnostic or therapeutic plan | A plan is presented to the client. The client and the clinician together then agree on a plan. |

| Diagnostic and laboratory aids | Simple and inexpensive office diagnostic procedures that confirm or rule out any of the most likely (first three or four) differential diagnostic possibilities should be done. |

| More complex or expensive diagnostic tests or procedure are then recommended. | |

| Clients may elect to forgo these tests and pursue less likely differential diagnostic possibilities in attempts to save money. Often, this approach is not cost-effective when the expense of inefficient medications and repeated examination is considered. | |

| Trial therapy | Clients may elect to pursue a therapeutic trial instead of diagnostic procedures. Trial therapies should be selected so that further diagnostic information is obtained. Generally, glucocorticoids are not acceptable because little diagnostic information is obtained. |

| Narrowing the differential diagnosis | Plan additional tests, observations of therapeutic trials, and reevaluations of signs and symptoms to narrow the list and provide a definitive diagnosis. |

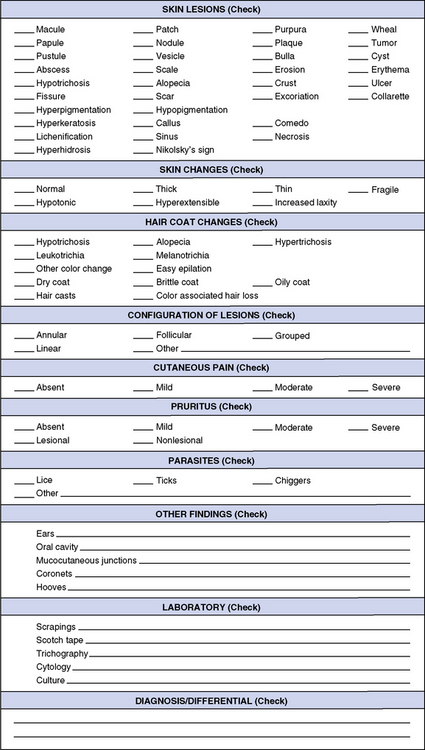

Records

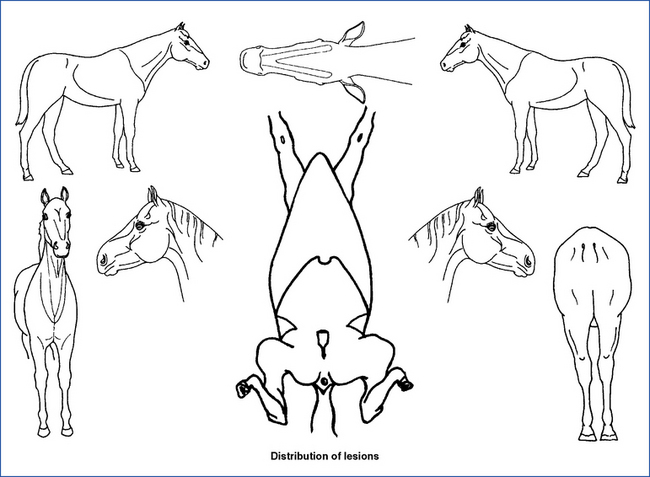

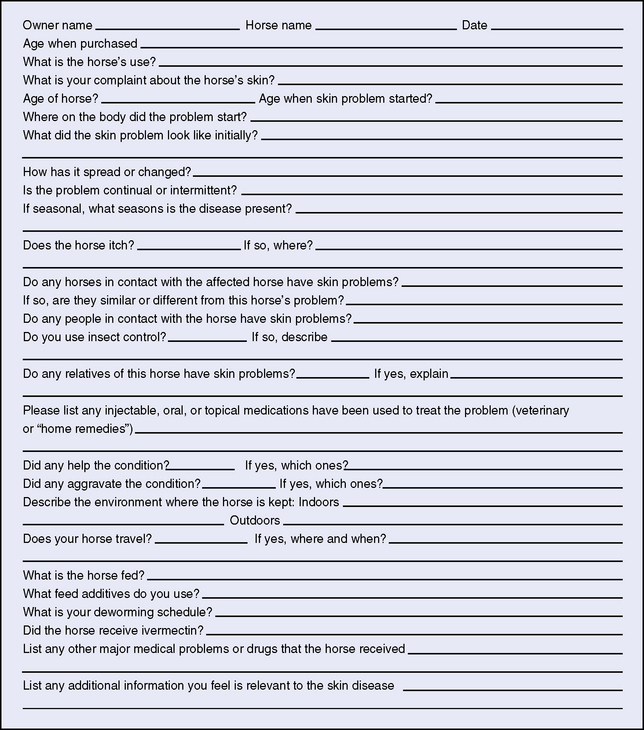

Fig. 2-1 is a record form for noting physical examination and laboratory findings for dermatology cases. Most important, the form leads the clinician to consider the case in a systematic manner. It also enables one to apply pertinent descriptive terms, saves time, and ensures that no important information is omitted. This form details only dermatologic data and should be used as a supplement to the general history and physical examination record. A special dermatologic history form is also useful, especially for patients with allergies and chronic diseases (Fig. 2-2).

Figure 2-2 Dermatology history sheet

(diagram taken from Pascoe RRR, Knottenbelt DC: Manual of equine dermatology, Philadelphia, 1999, Saunders).

History

Breed

Breed predilection determines the incidence of some skin disorders (Table 2-2, Table 16-1).

TABLE 2-2 Possible Breed Predictions for Nonneoplastic Skin Diseases

| Breed | Disease |

|---|---|

| American saddlebred | Epidermolysis bullosa |

| Appaloosa | Follicular dysplasia, mane and tail |

| Arabian | Atopic dermatitis |

| Coat color dilution lethal (lavender foal syndrome) | |

| Hypotrichosis | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | |

| Spotted leukotrichia | |

| Vitiligo | |

| Belgian | Chronic progressive lymphedema |

| Epidermolysis bullosa | |

| Linear epidermal hamartoma | |

| Clydesdale | Chronic progressive lymphedema |

| Connemara | Insect-bite hypersensitivity |

| Curly coat phenotype | Follicular dysplasia, mane and tail |

| Friesian | Insect-bite hypersensitivity |

| Icelandic | Insect-bite hypersensitivity |

| Morgan | Atopic dermatitis |

| Quarter horse | Atopic dermatitis |

| Cutaneous asthenia | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | |

| Linear alopecia | |

| Linear keratosis | |

| Reticulated leukotrichia | |

| Unilateral papular dermatosis | |

| Shetland | Insect-bite hypersensitivity |

| Steatitis | |

| Shire | Chronic progressive lymphedema |

| Coronary band dysplasia | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | |

| Spotted leukotrichia | |

| Standardbred | Calcinosis circumscripta |

| Linear keratosis | |

| Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease | |

| Reticulated leukotrichia | |

| Thoroughbred | Atopic dermatitis |

| Cellulitis | |

| Linear keratosis | |

| Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease | |

| Reticulated leukotrichia | |

| Spotted leukotrichia | |

| Trait Breton | Epidermolysis bullosa |

| Trait comtois | Epidermolysis bullosa |

| Warmblood | Atopic dermatitis |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity |

Medical History

The clinician should obtain a complete medical history in all cases. In practice, two levels of history are taken. The first level includes those questions that are always asked, and this level is often helped by having the client fill out a history questionnaire before the examination (see Fig. 2-2). Often, the answers on these forms will change if the client is questioned directly, so these form answers should be reviewed and not relied on as initially answered. The first level should initially include questions about previous illnesses and problems. The second level in history taking relates to more specific questions that relate to specific diseases. These more pertinent questions are usually asked once the practitioner has examined the animal and is developing a differential diagnosis or has at least established what some of the problems are. However, it is vital to use a systematic, detailed method of examination and history taking so that important information is not overlooked. A complete history takes a lot of time to obtain and usually is a major component of the initial examination period. In practice, many veterinarians do not take the time to collect a thorough history for the problem. Learning which historical questions are most important for specific problems and being certain to collect this information becomes critical. Often, the history is completed during the examination and once the initial differential diagnosis is determined.

Physical examination

Morphology of Skin Lesions

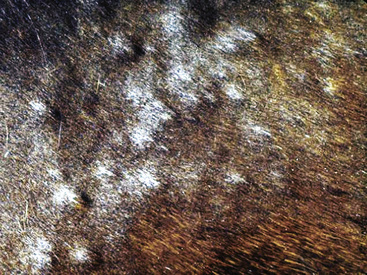

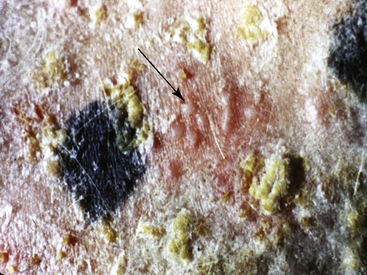

The following illustrations can help the clinician identify primary and secondary lesions. Also, the character of the lesions may vary, implying a different pathogenesis or cause. The definitions and examples in Figs. 2-3–2-27 explain the relationship of skin lesions to equine dermatoses.

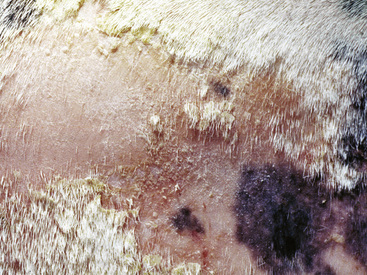

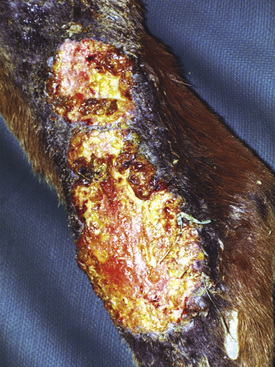

Figure 2-5 Papules, which proceed to oozing, crusting, and alopecia

(photograph illustrates bacterial pseudomycetoma).

Figure 2-6 Plaque—a larger, flat-topped elevation formed by the extension or coalescence of papules

(photograph illustrates an ulcerated plaque on leg caused by Rhodococcus equi).

Figure 2-12 Wheal—may also be polycyclic (ringlike, arciform, serpiginous) in appearance

(photograph illustrates urticaria in an allergic horse).

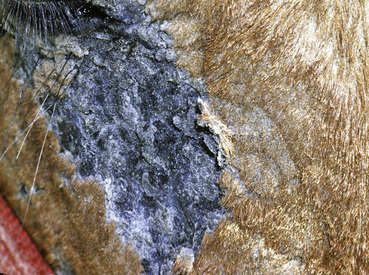

Figure 2-23 Scar—an alopecic, often depigmented area of fibrous tissue that has replaced severely damaged skin

(photograph illustrates a chronic pressure sore with scar formation and central ulceration).

Distribution Patterns of Skin Lesions

The study of skin diseases involves understanding the primary lesions that occur and the typical distribution patterns. Diseases less commonly present with atypical patterns. The combination of the type of lesions present and their distribution is the basis for developing a differential diagnosis. The distribution pattern may be very helpful by allowing clinicians to establish the differential diagnosis based on the region involved when animals have lesions and symptoms confined to certain regions (Tables 2-3 and 2-4). In some instances, this regional pattern is such a major feature that it is a required aspect of the disease. Cutaneous reaction patterns are also a very useful prompter for establishing a differential diagnosis (Table 2-5).

TABLE 2-3 Regional Differential Diagnosis for Nonneoplastic Dermatosesa

| Region | Common Diseases | Uncommon/Rare Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Head | ||

| Dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Besnoitiosis |

| Black fly bites | Cutaneous lupus erythematosus | |

| Dermatophytosis | Demodicosis | |

| Dermatophilosis | Food allergy | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | Forage mites | |

| Photodermatitis (white skin) | Multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease | |

| Staphylococcal folliculitis | Onchocerciasis | |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | ||

| Poultry mites | ||

| Sarcoidosis | ||

| Sarcoptic mange | ||

| Stachybotryotoxicosis | ||

| Trombiculiasis | ||

| Vaccinia | ||

| Nodules (see Table 15-1) | ||

| Noninflammatory hair loss | Alopecia areata | |

| Seasonal hypotrichosis | ||

| Pinnae | ||

| Dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Food allergy |

| Black fly bites | Psoroptic mange | |

| Dermatophytosis | Sarcoptic mange | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | Trombiculiasis | |

| Photodermatitis (white skin) | Vasculitis | |

| Nodules (see Table 15-1) | ||

| Neck | ||

| Dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Demodicosis |

| Black fly bites | Erythema multiforme | |

| Dermatophilosis | Forage mites | |

| Dermatophytosis | Linear keratosis | |

| Horse fly bites | Onchocerciasis | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | Sarcoptic mange | |

| Pediculosis | Sterile eosinophilic folliculitis | |

| Stable fly bites | Trombiculiasis | |

| Staphylococcal folliculitis | ||

| Urticaria | ||

| Nodules (see Table 15-1) | ||

| Noninflammatory hair loss | Alopecia areata | |

| Linear alopecia | ||

| Trunk | ||

| Dermatitis | Dermatophilosis | Demodicosis |

| Dermatophytosis | Linear keratosis | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | Sterile eosinophilic folliculitis | |

| Pediculosis | Unilateral papular dermatosis | |

| Staphylococcal folliculitis | ||

| Urticaria | ||

| Nodules (see Table 15-1) | ||

| Ventrum (Abdomen, Groin, Axillae, Chest) | ||

| Dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Besnoitiosis |

| Black fly bites | Food allergy | |

| Horn fly bites | Louse flies | |

| Horse fly bites | Malassezia dermatitis | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | Onchocerciasis | |

| Stable fly bites | Pelodera dermatitis | |

| Poultry mites | ||

| Trombiculiasis | ||

| Nodules (see Table 15-1) | ||

| Legs | ||

| Dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Besnoitiosis |

| Black fly bites | Cannon keratosis | |

| Chorioptic mange | Food allergy | |

| Chronic progressive lymphedema | Forage mites | |

| Dermatophilosis | Pemphigus foliaceus | |

| Dermatophytosis | Poultry mites | |

| Horse fly bites | Strongyloidosis | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | Trombiculiasis | |

| Photodermatitis (white skin) | Vasculitis | |

| Stable fly bites | Zinc-responsive dermatitis | |

| Staphylococcal folliculitis | ||

| Nodules (see Table 15-1) | ||

| Mane and tail | ||

| Dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis | Food allergy |

| Chorioptic mange | Oxyuriasis | |

| Insect-bite hypersensitivity | Psoroptic mange | |

| Pediculosis | Seborrhea | |

| Nodules (see Table 15-1) | ||

| Noninflammatory hair loss | Alopecia areata | |

| Follicular dysplasia | ||

| Genetic hypotrichosis | ||

| Mimosine toxicosis | ||

| Piedra | ||

| Selenosis | ||

| Trichorrhexis nodosa | ||

a Cutaneous adverse drug reactions can mimic ANY dermatitis (see Chapter 9) and contact dermatitis can affect ANY body region (see Chapters 8 and 13).

TABLE 2-4 Common Localizations of Neoplasms, Cysts, Hamartomas, and Keratosesa

| Neoplasms | |

| Viral papillomas | Muzzle, lips, pinnae, genitalia |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Mucocutaneous junctions (especially eyelids and genitalia), nonpigmented/lightly haired areas |

| Basal cell tumor | Distal legs, trunk, face, neck |

| Epitrichial sweat gland tumor | Pinnae, vulva |

| Sarcoid | Pinnae, lips, periocular area, neck, legs, ventrum |

| Fibroma | Periocular area, neck, legs |

| Fibrosarcoma | Periocular area, trunk, legs |

| Hemangioma | Distal legs |

| Hemangiosarcoma | Head, neck, trunk, proximal legs |

| Lymphangioma | Axillae, groin |

| Lipoma | Trunk, proximal legs |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | Neck, proximal legs |

| Mast cell tumor | Head, legs |

| Nonepitheliotropic lymphoma | Head, neck, trunk, proximal legs |

| Melanocytoma | Legs, trunk |

| Melanoma | Perineum, ventral tail |

| Cysts | |

| Dermoid cyst | Dorsal midline |

| Follicular cyst | Distal legs, head |

| Heterotopic polyodontia | Base of ear |

| Hamartoma | |

| Linear epidermal hamartoma | Caudal cannon bone/pastern area of hind legs |

| Keratosis | |

| Actinic keratosis | See Squamous Cell Carcinoma above |

a See Chapter 16 for details.

TABLE 2-5 Differential Diagnosis for Some Cutaneous Reaction Patterns

| Nodules | See Table 15-1 |

| Pastern dermatitis | See Table 15-3 |

| Coronary band disorders | See Table 15-4 |

| Head shaking | See Table 15-5 |

| Mucocutaneous junctions | Mucocutaneous pyoderma, candidiasis, Malassezia dermatitis, vesicular stomatitis, Jamestown Canyon virus, pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, vasculitis, epidermolysis, bullosa (neonates), neonatal ulcerative dermatitis/thrombocytopenia/neutropenia (neonates), zinc-responsive dermatitis, stachybotryotoxicosis, multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease |

| Gangrene/necrosis | External pressure (e.g., pressure sore), internal pressure (e.g., severe edema), burns, frostbite, snake bite, ergotism, vasculitis, clostridial infection, Salmonella septicemia (foals) |

| Subcutaneous emphysema | Tracheal rupture, pneumomediastinum, penetrating wounds, clostridial infection |

| Exfoliative dermatitis (widespread scale/crust/alopecia) | Dermatophytosis, dermatophilosis, pemphigus foliaceus, contact dermatitis, sarcoidosis, multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease, cutaneous adverse drug reaction, systemic lupus erythematosus, primary seborrhea, epitheliotropic lymphoma, dietary deficiency, iodism, arsenic poisoning |

| Depigmentation | Postinflammatory (e.g., viral papillomatosis, pressure sore, ventral midline dermatitis, injury), cutaneous lupus erythematosus, herpes coital exanthema, vesicular stomatitis, dourine, vitiligo, reticulated leukotrichia, spotted leukotrichia, hyperesthetic leukotrichia, copper deficiency |

| Noninflammatory hair loss | Abnormal shedding, anagen defluxion, telogen defluxion, follicular dysplasia (e.g., mane and tail) (young), genetic hypotrichosis (young), seasonal hypotrichosis (especially face), alopecia areata (also mane and tail), selenosis (mane and tail), mimosine toxicosis (mane and tail), trichorrhexis nodosa, piedra |

| Tail/rump rubbing | Atopic dermatitis, insect-bite hypersensitivity, food allergy, pediculosis, chorioptic mange, psoroptic mange, Malassezia dermatitis (groin area), herpes coital exanthema, oxyuriasis, cutaneous adverse drug reaction, behavioral |

Laboratory procedures

Surface Sampling Plan

Deep skin scrapings

Diagnosis of demodicosis is made by demonstrating multiple adult mites, finding adult mites from multiple sites, or finding immature forms of mites (ova, larvae, and nymphs). Horses harbor two species of Demodex mites, Demodex caballi, and D. equi (see Chapter 6). Scrapings taken from a normal horse, especially from the face, may contain an occasional adult mite. If one or two mites are observed, repeated scrapings should be done. Multiple positive results of scrapings from different sites should be considered abnormal. Observing whether the mites are alive (mouthparts or legs moving) or dead is of prognostic value while the animal is being treated. As a case of Demodex infestation responds to treatment, the ratio of live to dead mites decreases, as does the ratio of eggs and larvae to adults. If this is not occurring, the treatment regimen should be reevaluated.

Diagnosis of Pelodera dermatitis is made by demonstrating any Pelodera strongyloides nematodes (see Chapter 6).

Superficial skin scrapings

The most common chigger mite is Eutrombicula alfreddugesi (see Chapter 6). These mites can be seen with the naked eye. They appear as bright orange objects adhering tightly to the skin or centered in a papule. They are easily recognized by their large size, relatively intense color, and tight attachment to the skin. They should be covered with mineral oil and picked up with a scalpel blade. A true skin scraping is not needed. However, when removed from the host for microscopic examination, they should immediately be placed in mineral oil, or they may crawl away. Only the larval form is pathogenic, and these have only six legs.

Hair Examination

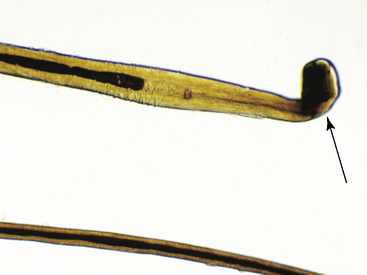

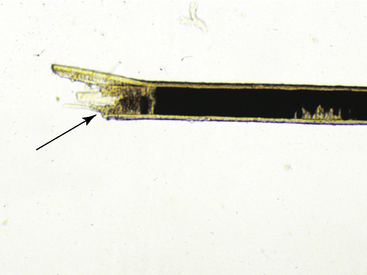

Hairs will have either an anagen or telogen root (bulb). Anagen bulbs are rounded, smooth, shiny, glistening, and often pigmented and soft, so the root may bend (Fig. 2-28). Telogen bulbs are club- or spear-shaped, rough-surfaced, nonpigmented, and generally straight (Fig. 2-29). A normal hair shaft is uniform in diameter and tapers gently to the tip. All hairs should have a clearly discernible cuticle and a sharply demarcated cortex and medulla. Hair pigmentation depends on the coat color and breed of horse, but should not vary greatly from one hair to the next in regions where the coat color is the same.

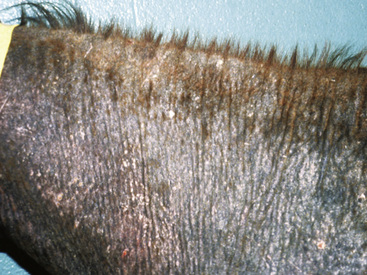

Normal adult animals have an admixture of anagen and telogen hairs, the ratio of which varies with season, management factors, and a variety of other influences (see Chapter 1). No normal animal should have all of its hairs in telogen (Fig. 2-30); therefore, this finding suggests a diagnosis of telogen defluxion or follicular arrest (see Chapter 10).

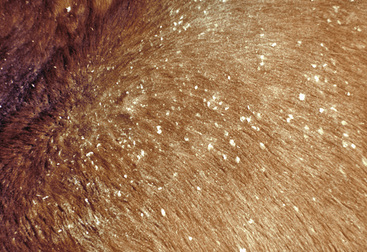

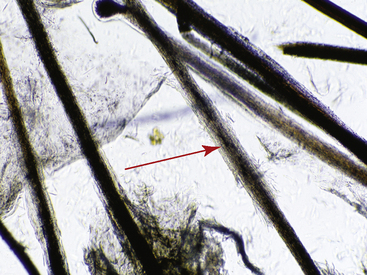

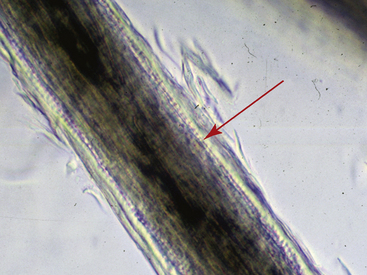

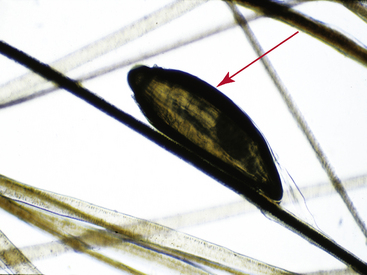

Examination of the hair shaft follows bulbar evaluation. Hairs that are inappropriately curled, misshapen, and malformed suggest an underlying nutritional, metabolic, or hereditary disease (Fig. 2-31). Hairs with a normal shaft that are suddenly and cleanly broken (Fig. 2-32) or longitudinally split (trichoptilosis) indicate external trauma from excessive rubbing, chewing, licking or scratching, or too vigorous grooming. Breakage of hairs with abnormal shafts can be seen in congenitohereditary disorders (see Chapter 14), trichorrhexis nodosa (see Chapter 10), anagen defluxion (see Chapter 10), alopecia areata (see Chapter 9), and dermatophytosis (Figs. 2-33 and 2-34; see Chapter 5). Abnormalities in hair pigmentation have not been well-studied. When unusual pigmentation is observed, external sources (e.g., chemicals and topical medications, sun bleaching) or conditions that influence the transfer of pigment to the hair shaft (e.g., drugs, nutritional imbalances, endocrine disorders, idiopathic pigmentary disorders) must be considered. Hair casts are usually seen in diseases associated with follicular keratinization abnormalities, such as primary seborrhea and follicular dysplasia. Hair casts should not be confused with louse nits (Fig. 2-35).

Cytologic Examination

Cytologic findings

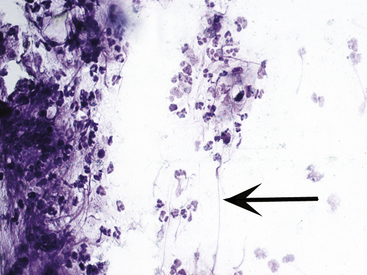

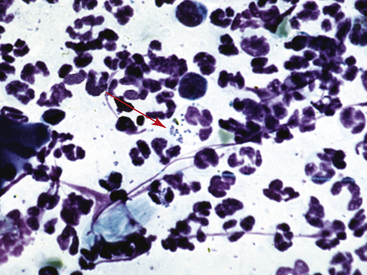

It is also possible to obtain some clues as to the type of bacterial pyoderma or the underlying condition. In general, deep infections have fewer bacteria present, with the vast majority being intracellular. In addition, deep infections have a mixed cellular infiltrate with large numbers of neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. The presence of these cells suggests that longer-term antibiotic therapy is necessary. Large numbers of intracellular and extracellular cocci are seen more commonly in superficial bacterial infections (Figs. 2-36 and 2-37), and the inflammatory cells are almost exclusively neutrophils.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree