Chapter 14 Diagnosis and Treatment of Otitis Media

Otitis media is a common disease process that often goes unrecognized in most veterinary practices. The fact that otitis media is present in more than half of all canine patients with chronic otitis externa should stimulate a reformulation of the diagnostic process when faced with these cases. Just the common history that the patient has been treated repeatedly for ear infections should alert the veterinarian to think about otitis media as a possibility.

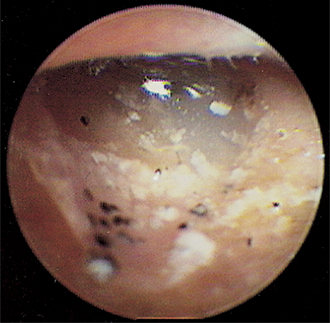

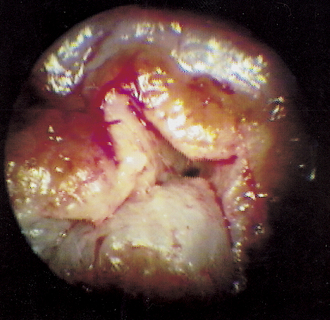

Otitis media in dogs is much more prevalent than previously thought. In dogs, secondary otitis media occurs in approximately 16% of acute otitis externa cases and as many as 50% to 80% of chronic otitis externa cases.1,2 Many cases of otitis media are well hidden from visual detection by the significant exudates present in the ear canal and the severe pathologic changes that have occurred in the ear canal as a result of chronic otitis externa. These changes include stenosis, fibrosis, tumors, polyps, epithelial hyperplasia, and glandular hyperplasia (Figure 14-1). Chronic changes in the external ear canal prevent adequate visualization beyond these blockages, so determining the integrity of the eardrum is not always possible.

Figure 14-1 Stenotic ear. Extensive fibrosis in the horizontal ear canal prevents visual examination of the TM.

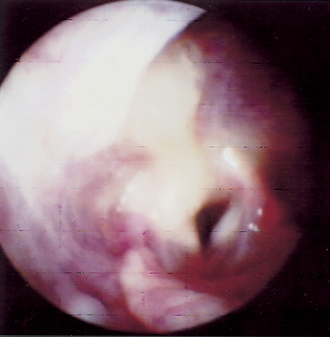

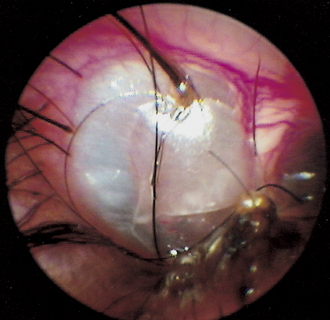

Some dogs with otitis media have intact eardrums but also have significant bacterial and yeast populations that can be isolated from the middle ear.2 These dogs may have had a ruptured eardrum that healed, trapping bacteria and yeast in the tympanic bulla. Therefore the presence of an eardrum does not rule out otitis media. Healed eardrums trap infectious organisms in the middle ear, and suppurative otitis media results (Figure 14-2). Secretions and exudates are trapped behind the healed eardrum, causing it to bulge outward under pressure, which in turn causes severe pain. Myringotomy may be necessary to investigate the contents of the bulla in suspected cases of otitis media where the eardrum is intact.

Figure 14-2 The TM is opaque and cystic. Serous fluid behind the eardrum causes increased pressure on the eardrum.

Signalment and History

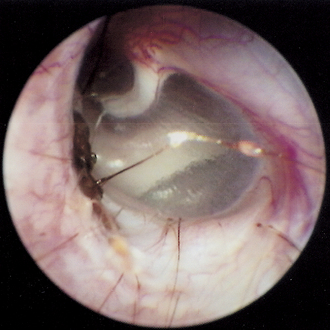

More commonly, a dog with otitis media will have a history of recurrent or chronic bacterial external ear infections. Perhaps the pet owner will present all the external ear medications already tried on the pet; that is a signal for the veterinarian to look deeper in the ear canal for middle ear disease. Chronic otitis media is almost always suppurative, with large amounts of fluid draining into the ear canal. The presence of liquid in the ear canal may signal otitis media (Figure 14-3).

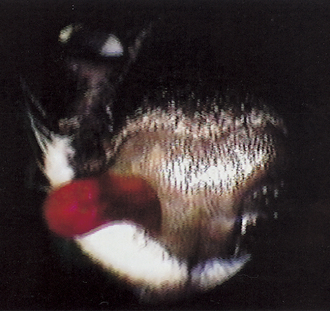

When otitis media affects the nerves that course around the base of the ear or through the tympanic bulla, the patient may show signs as subtle as keratoconjunctivitis sicca on the ipsilateral side. This results from damage to the palpebral branch of the facial nerve. When otitis media affects the sympathetic nerves from the facial and trigeminal nerves coursing through the middle ear, the patient may show mild signs of Horner’s syndrome (enophthalmos, ptosis, and miosis) (Figure 14-4). Some patients may show pain, head tilt, or, with facial nerve palsy, a drooped lip, drooped ear, or loss of the ability to close the eyelid, leading to exposure keratitis.3 Since the facial nerve courses in and around the ear canal, it is easily affected by swelling, inflammation, and trauma from the dog scratching at the base of the ear. Facial neuropathy should be suspected if there is drooping of the facial muscles and skin or drooling of saliva because the lips and facial muscles cannot create an oral seal. Peripheral vestibular disease with nystagmus and circling may be evident if the infection and inflammation have affected the inner ear.

If there is pharyngeal drainage of mucus and exudates resulting from otitis media, the patient may be presented for inspiratory stridor. In these cases, a pharyngeal examination may reveal a nasopharyngeal polyp interfering with breathing or thick mucus draining from the auditory osteum in the nasopharynx, covering the caudal pharynx, and occluding the airway (Figure 14-5).

Evaluation of the Patient

If there is significant stenosis of the external ear canal, either from inflammation or from permanent pathologic changes to the ear canal, the eardrum may not be adequately visualized. Patient preparation using potent topical and/or systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 mg/lb daily for 10 to 14 days, then taper or dexamethasone 2 mg/ml at a dose of 0.1 mg/lb intramuscularly [IM] once) may be needed to reduce otic inflammation and allow examination of the TM on a subsequent visit. If permanent changes to the ear canal prevent visual determination of the integrity of the eardrum, other techniques are used to identify disease proximal to the stenosis.

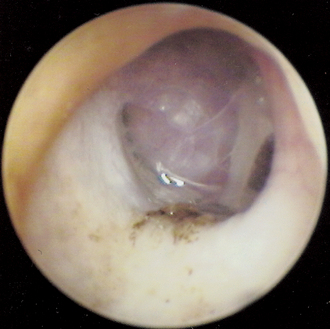

After the veterinarian is comfortable looking at normal eardrums—the location, color, clarity, and the normal tension on it—using the TM to diagnose otitis media becomes much easier. If the eardrum remains translucent, the middle ear can be transilluminated with the bright light from the video otoscope and the contents of the middle ear can be visualized (Figure 14-6).

In obvious cases of canine otitis media, there is no eardrum present. The ear canal is filled with a liquid secretion, often with flecks of material mixed with it. A mucus-filled ear canal may alert the clinician to otitis media. Most patients with chronic otitis externa that has been present for 45 to 60 days will have a coexisting otitis media. In otitis externa, purulent exudates and proteolytic enzymes elaborated by inflammatory cells have a caustic effect on the thin epithelium of the eardrum, causing it to become necrotic, weaken, and eventually rupture. When this happens, hairs, ceruminous secretions, exudates, and infectious bacteria or yeast organisms in the external ear move into the middle ear. In these patients it is difficult to visualize any part of the eardrum, since it may not be present at all. Sometimes only a small ring of granulation tissue may be seen at the annulus fibrosus, where the eardrum attaches to the ear canal. With the otoscope, an otitis media case without suppuration looks like a deep, dark hole. The mucosa becomes dark as it becomes hyperemic, and brownish ceruminous exudates fill the bulla.

In some cases of otitis media the eardrum is intact, but it may look abnormal. It may change color in response to inflammation on the medial side, becoming opaque and gray in color rather than pearly and translucent. Sometimes there is fluid behind the eardrum, and examination of the intact TM may indicate that it is bulging into the external ear. Purulent material in the middle ear may be seen as yellow fluid behind the eardrum. Early polyps and tumors in the middle ear may be seen as fleshy masses through the eardrum (Figure 14-7).

Imaging of the Tympanic Bulla

Radiographic assessment of the bullae can be very helpful in determining the extent of bony involvement and the presence of increased tissue or fluid filling the bullae (see Chapter 2). However, the absence of radiographic changes in the bullae does not rule out otitis media, especially the more acute cases.

In a dog with minimal bony changes, the bullae appear as normal, eggshell-thin circular structures medial to the mandibular rami on the rostrocaudal view. The cortical outline is thin and the middle of the bullae radiolucent because the bullae are filled with air. The cat has an air-filled, two-chambered tympanic bulla separated by a bony septum.

Is the Eardrum Ruptured?

Several techniques have been described to determine the integrity of the TM when it cannot be visualized in an ear with a stenotic external ear canal.4 A small-diameter (3½ to 5 Fr) catheter can be inserted into the ear canal until it stops. It is then extended and retracted to get a feel for the rigidity of the “stop.” If there is a spongy feel, the eardrum is intact. If there is a definite hard feel to the “stop,” the eardrum is ruptured and the catheter is hitting the medial wall of the tympanic bulla. This technique should be practiced on cadaver specimens to acquire the necessary sensitivity.

An easy, indirect method for determining the integrity of the eardrum is to infuse warmed, very dilute povidone-iodine solution (or dilute fluorescein solution) into the ear canal with the anesthetized dog or cat in lateral recumbency. If the orange or yellow-green flushing fluid comes out of the nose or if the patient snorts out this solution through the oropharynx when pressure is applied by the flushing fluid, the eardrum is ruptured (Figure 14-8). The fluid has flowed from the external ear canal through the ruptured eardrum, into the tympanic bulla, and through the auditory tube into the nasopharynx.

Figure 14-8 Nasal drainage of dilute povidone iodine flushed from the middle ear during ear cleaning.

Positive contrast canalography has been described as a method for detecting a ruptured TM in dogs with otitis media.5 Two to 5 ml of dilute iodinated contrast agent is instilled into the ear canals of these anesthetized patients while in lateral recumbency with the affected ear up. The author uses 0.3 ml of Hypaque 50% or similar contrast agent in 2.7 ml of saline. In a stenotic ear canal, a 3½ or 5-Fr catheter is threaded into the stenosis if possible. Contrast agent is then infused beyond the stenosis. An open-mouth view of the bullae is then taken, using a horizontal x-ray beam. If the eardrum is intact, there will be a distinct contrast/air interface at the eardrum. If the eardrum is not intact, the contrast material will enter the bulla, and a continuous column of contrast will extend into the bulla.

In a study of this technique, eardrums of cadaver dogs with normal ear canals and intact eardrums were intentionally ruptured and contrast material was introduced into the external ear canal. In every case, contrast media entered the tympanic bulla and was detected by a radiograph. In clinical otitis media cases, positive-contrast canalography was positive in most of the cases where the eardrum was determined to be ruptured otoscopically, and it was positive for other cases in which the eardrum appeared to be intact otoscopically. In normal ears, canalography was more accurate for detecting iatrogenic TM perforation than otoscopy.5

Primary Otitis Media in Cats

In many species, including humans, rats, pigs, and cattle, Mycoplasma has been reported as an inducing agent in middle ear disease.6 In addition to the more common streptococci and staphylococci isolated from clinical feline otitis media cases, organisms much more difficult to culture and identify, such as Mycoplasma and Bordetella, have also been cultured from the middle ear of cats with otitis media.7,12 It is unclear what role these upper respiratory bacteria may play in the pathogenesis of feline otitis media. It is also unclear whether anaerobic organisms may be involved when the eardrum is intact and the auditory tube swells, thus sealing these bacteria within the bulla. In the author’s experience, treatment of cats with otitis media using azithromycin (Zithromax Oral Suspension, Pfizer), which has excellent activity against both Mycoplasma and Bordetella, at a dose of 5 mg/lb every 48 hours for two or three treatments, hastens recovery from otitis media. Often, culture and/or cytology do not reveal an infectious organism. This raises the question of whether allergy, viruses, and/or fungi have a role in middle ear disease in dogs and cats.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree