Chapter 3 Cytology and Histopathology of the Ear in Health and Disease

Cytology

Otitis externa is a multifactorial disorder affecting the quality of life of 10% to 20% of dogs and 2% to 6% of cats presenting to veterinarians.1–3 Although a common problem, management of otitis externa is frequently challenging. Seemingly simple cases can become complicated by treatment failure, recurrence, and progressively worsening physical changes. Successful management of otitis requires accurate identification and management of both the primary cause (e.g., atopy, adverse food reaction, parasites, neoplasia) and concurrent perpetuating factors (e.g., bacterial or yeast infection, edema, glandular hyperplasia, loss of epithelial migration, otitis media).

Observation of quality and odor of exudates found during physical examination provides practitioners with a rough guide regarding potential organisms present in the external canal. Classically, dry, grainy, black discharge is most often associated with Otodectes cynotis infestations; waxy, brown exudates indicate Malassezia4; and yellow discharge indicates bacterial infection. Unfortunately these observations are not consistent or reliable.5,6 Veterinarians should not make a diagnosis or select therapy based on past experience, physical character of discharge, or odor. Instead, decision making should be based on cytologic evidence established by careful microscopic evaluation. Failure to do so may result in misidentification of the most relevant pathogen and inappropriate selection of antimicrobial therapy. The consequence is often poor case management, prolongation of treatment, or even treatment failure and progression of disease. Cytology should be viewed as a routine diagnostic test for every patient with clinically significant ear disease.

Technique

In order to obtain the best diagnostic slide, be prepared to collect the sample prior to introduction of any cleaning agent or other therapy. In most cases, material obtained from the deeper horizontal canal is more clinically relevant than material obtained from the superficial vertical canal.5,7 In well-behaved or anesthetized dogs, the ideal sample is obtained by inserting a cotton-tipped applicator through a disinfected otoscopic cone positioned beyond the junction of the vertical and horizontal canals. The cone shields the swab from contents of the vertical canal, which may contain numerous, irrelevant commensal organisms. Once in position, the swab is extended beyond the cone and pressure is applied laterally against the epithelium, collecting the exudates; the swab is then pulled back into the cone and removed from the canal. Unfortunately, with an awake patient, safely inserting a swab into a painful deep horizontal canal can be challenging at best. The presence of stenosis, inflammation, and voluminous exudate makes the exercise difficult and potentially dangerous if the patient moves suddenly or unpredictably. Overaggressive insertion of the swab into the patient’s ear canal in an effort to obtain the deepest possible sample may result in further damage to irritated epithelium, or worse, in accidental perforation of the tympanic membrane. To obtain consistent samples in awake or painful patients, veterinarians should aim for the junction of the vertical and horizontal canals, where the cartilage bends at a 75-degree angle. If the veterinarian avoids straightening the canal, the bend should prevent the swab from advancing too deeply and damaging the tympanic membrane. Veterinarians who are gentle, cautious, and quick can safely obtain a diagnostic sample from the majority of patients. In patients anesthetized for ear flush, otoscopy, or other procedures, time should be taken to collect an ideal specimen properly from the deep horizontal canal or in some cases the tympanic cavity.

A separate cytologic specimen should always be prepared from both the right and the left ear canals, even if the patient presents for unilateral disease. Separate evaluation allows for comparison between the diseased ear and the normal ear, as well as early recognition of bacterial or yeast overgrowth in the less obviously affected ear. In patients with bilateral disease, clinically relevant differences in bacteria and yeast are common when comparing the two sides.8,9 Without independent evaluation, documentation, or monitoring of each ear separately, veterinarians may fail to make appropriate management decisions.

In the case of otitis media, systemic therapy and bulla infusions of antibiotics should be directed at organisms colonizing the middle ear rather than the external canal. In one study, isolates from the tympanic cavity differed from isolates from the horizontal canal in 89.5% of cases.8 In the same study, the tympanic membrane appeared to be intact in 71.1% of the ears with proven otitis media. If otitis media is suspected and the tympanum appears to be intact, sample collection should be performed by myringotomy—the intentional perforation of the tympanic membrane with a sterile swab, needle, or catheter. Because organisms from the middle ear may be coated in mucus, which prevents adequate uptake of stain, cytology from the middle ear should always be accompanied by a sample for culture and sensitivity obtained at the same time. In the external canal, cytology has been shown to be more sensitive than culture and sensitivity5,10; but this is not always the case in samples collected from the tympanic cavity.8

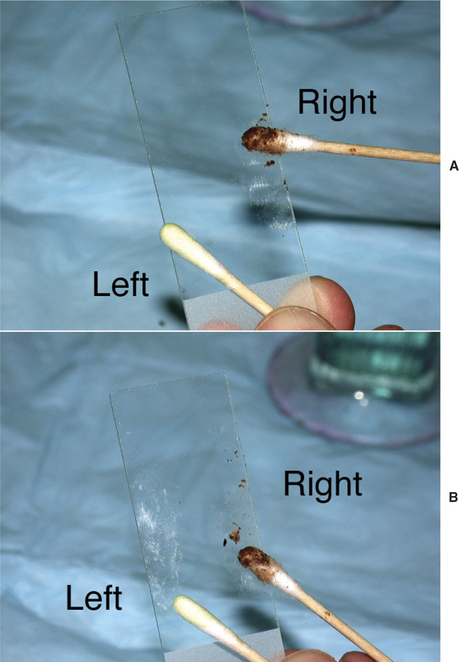

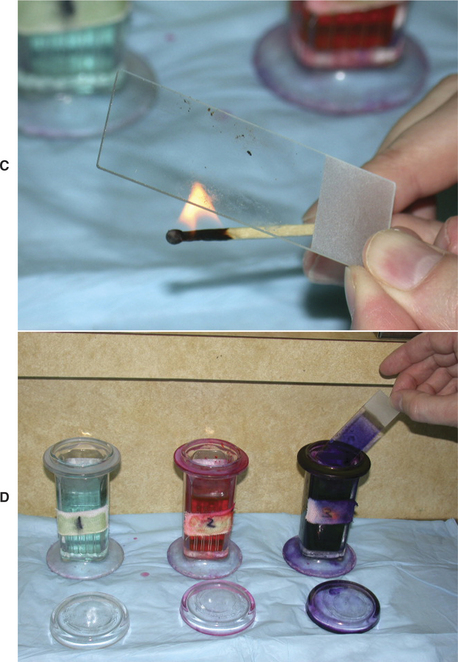

Once the sample is collected, roll the swab or curette onto a clean glass slide, evenly distributing a thin layer of material (Figure 3-1). Label each slide to identify correctly which ear was sampled. Alternatively, using one slide with a frosted end, holding the frosted end toward oneself, roll the sample from the left ear on the left part of the slide and the sample from the right ear on the right part of the slide. The precise method for marking slides is less important than consistency. Because cerumen has high lipid content, briefly heat the slide with an open flame to fix the material to the glass. This precaution will prevent loss of valuable information into the stain solvent. Avoid overheating the slide; excess heat will distort cells and organisms. Stain selection is a matter of personal preference; however, the same stain should be used for all samples in order to gain familiarity and produce consistent and reliable results. A modified Wright’s stain, such as Diff-Quik (Baxter Scientific Products, McGraw Park, Illinois) is recommended. Modified Wright’s stains are designed for evaluation of peripheral blood smears; therefore, leukocytes will retain easily recognized characteristics. Both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, as well as yeast, will appear blue or purple. Performing a gram stain is necessary to obtain this additional information, but extra staining is often an unnecessary and time-consuming task. In general, morphologically coccoid bacteria found in the ear canal are gram-positive organisms (e.g., Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus) and the majority of rod bacteria are gram-negative (e.g., Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., coliforms). Only Corynebacterium, a gram-positive coccobacillus, and less common organisms such as Actinomyces and Nocardia spp. and filamentous gram-positive rod bacteria do not follow this rule.

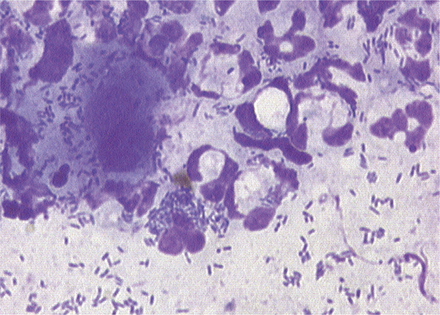

The high-dry, 40× objective (400× magnification) is adequate for identification of leukocytes, red blood cells, cornified epithelium, and neoplastic cells. Infectious organisms such as yeast and larger bacteria are also easily recognized. After examining several fields with the high-dry objective, switch to the high-magnification, oil-immersion lens (100× objective, 1000× magnification) for detailed evaluation. The higher magnification is necessary to identify smaller or lightly stained bacteria that may be easily missed with the high-dry objective. The high-oil magnification also permits detailed evaluation of the cytoplasm of neutrophils and macrophages for phagocytized bacteria—another important indicator of that particular organism’s acting as a pathogen rather than a commensal.

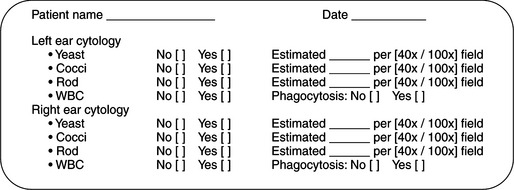

In order to maintain consistency in cytologic evaluation, each specimen should be specifically evaluated for the presence, estimated number, and morphologic characteristics of three specific features: yeast, bacteria, and leukocytes. To estimate the numbers, evaluate five to 10 areas, and record the average count per high-powered field (Figure 3-2). A complete record of all three cytologic features is necessary to monitor progression of disease or response to therapy. Recording “bacterial otitis” alone does not supply sufficient information for later comparison. Each cytologic description should contain information regarding the morphologic characteristic of bacteria (cocci or rod), the presence or absence of Malassezia and leukocytes, whether bacteria were phagocytized by leukocytes, and a semiquantitative estimation of the relative numbers of each type of organism seen. This level of detail permits either the primary clinician or any colleague following the case to determine accurately whether the “bacterial otitis” is resolving, changing, or worsening.

Normal Cytology

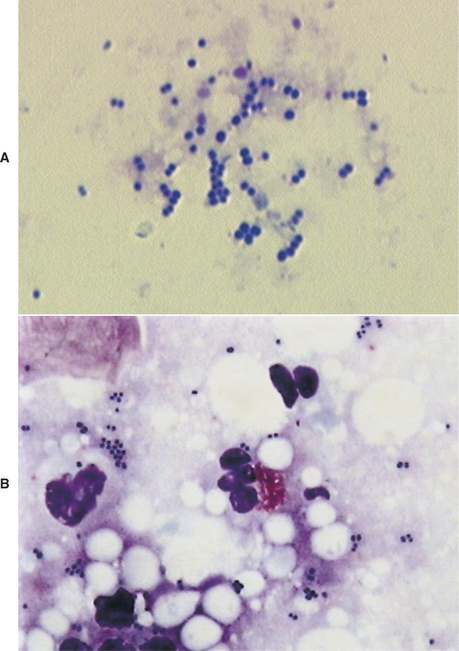

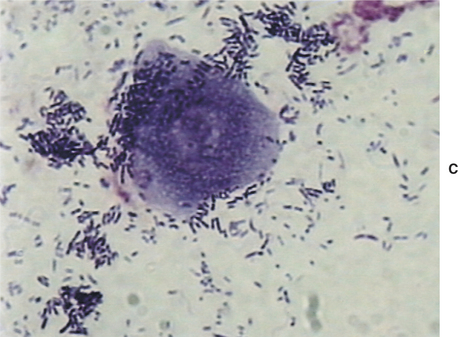

The external ear canals of dogs and cats contain small numbers of normal resident bacteria. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp., coagulase-positive Staphylococcus spp., and Streptococcus spp. are the most frequently isolated bacteria from normal ear canals. With the exception of Corynebacterium, rod-shaped bacteria are rarely found in normal ear canals.4,6,11 Any bacteria found in the presence of leukocytes should be considered abnormal.5–7 Because stain precipitate can resemble coccoid bacteria, high-oil magnification is necessary to visualize morphologic characteristics of bacteria. Clinically significant organisms should be symmetrical, have a distinct smooth edge, and be uniformly stained; they are typically present in pairs or chains of bacteria equal in size (Figure 3-3). In contrast, debris and precipitate vary in size and may be asymmetrical, irregular, and granular in appearance.

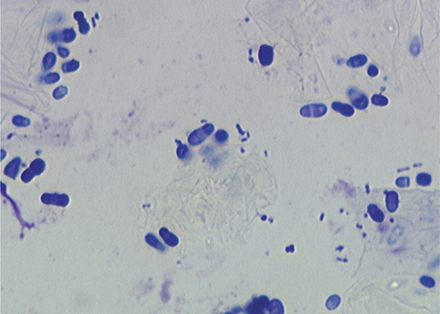

Another common finding on otic cytology is basophilic staining yeast, ranging in size from 2.0 μm × 4.0 μm up to 6.0 μm × 7.0 μm.12 For comparison, canine red blood cells are approximately 7.0 μm in diameter; feline red blood cells are 5 μm. The most commonly encountered yeast exhibits unipolar budding, which creates the commonly described “peanut,” “snowman,” or “footprint” shape, easily recognizable as Malassezia (Figure 3-4). Although these organisms are normal residents of the canine and feline ear canal, under the appropriate circumstances Malassezia can become important opportunistic pathogens, contributing directly to the severity of clinical signs, as well as to the progression and perpetuation of disease.

Because bacteria and yeast are considered normal inhabitants of the external ear canal, veterinarians need to determine whether the bacteria present cytologically are clinically relevant. In contrast, any finding of leukocytes on cytology is considered abnormal. The finding of bacteria that have been engulfed by phagocytic neutrophils and macrophages is one clear indication of relevance (Figure 3-5). The absence of leukocytes does not rule out the role of bacteria or yeast as pathogens. In general, heavy colonization of the canal by opportunistic pathogens is reflected in the number of bacteria seen per high-powered field. This semiquantitative method for determining clinical significance is discussed in detail in the sections on abnormal cytology.

Abnormal Cytology

Malassezia

Malassezia spp. can be found on cytology from up to 96% of dogs and 83% of cats with normal ear canals.10 Malassezia pachydermatis is widely recognized as the predominant commensal yeast of dogs.12–15 However, the genus actually consists of eight species, including seven distinct lipid-dependent species: M. furfur, M. sympodialis, M. globosa, M. obtusa, M. restricta, M. sloofiae, and M. equi.12,13 In dogs with otitis externa, Malassezia pachydermatis is present 83% of the time.16–18 Recent studies have demonstrated M. furfur and M. obtusa in 4.5% of cases of canine otitis externa, whereas M. sympodialis and M. furfur were present in 8.9% of diseased ear canals of cats.18,19 M. sympodialis,20,21 M. globosa,21 and M. furfur18,21 can be recovered from normal-haired skin, ear canals, and mucosa of healthy cats. Of these, M. sympodialis is believed to be a normal resident of the feline ear canal.15

Because the different species may have variable morphologic features and staining characteristics, veterinarians may notice unusually shaped yeast bodies on cytologic preparations. Most likely these variations represent multiple species of Malassezia. Current research demonstrates that different species have variable pathogenicity, virulence factors, and host responses; however, the clinical relevance of these differences has not been demonstrated.13 Unless there is a compelling reason to differentiate between Malassezia species using laboratory techniques, cytologic recognition of any member of the genus is sufficient for management of clinical cases.

Because Malassezia can be found in normal patients or mixed in with predominantly bacterial infections, veterinarians need to determine the clinical significance of Malassezia for each patient. Cytology is the most useful tool for differentiating between normal resident colonization and overgrowth. Unlike bacterial infections, suppurative inflammation is not a common feature of Malassezia otitis5 and therefore cannot be used to determine a pathologic state.

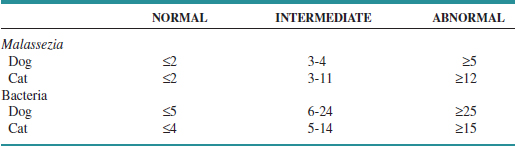

At what threshold does yeast become a contributing factor to disease rather than an incidental finding? Precise breakpoints for maximum acceptable number of yeast vary from patient to patient. Cytologic estimation of numbers can provide a guideline for the clinician; in the end, however, the decision to treat Malassezia depends on a combination of cytologic findings, severity of clinical signs, past history of yeast otitis, and response to previous therapy in that individual patient. A recent comparison of cytologic specimens from normal and diseased ears demonstrated that up to an average of two yeast per high-dry field (40× objective, 400× magnification) in the dog and cat should be considered normal.22 Mean counts greater than 5 yeast per field in dogs, and 12 yeast per field in cats are abnormal. Intermediate values are considered a gray zone (Table 3-1). These criteria had a specificity of 95% in dogs and 100% in cats. However, because the study included bacterial otitis, not all cases of otitis externa had yeast as a component; as a result, sensitivity was only 50% for dogs and 63% for cats. A study by Tater et al10 evaluated otic cytology from 50 normal dogs and 52 normal cats; it found a range of 0 to 2.6 yeast per high-dry field in dogs and 0 to 3.3 per high-dry field in cats. Diseased dogs were not included for comparison, but these findings would be consistent with previously reported normal breakpoints. The authors also demonstrated that ear conformation did not result in differences in normal yeast numbers when comparing dogs with pendulous pinna with dogs with erect ear carriage. Therefore, ear conformation should not influence interpretation of cytologic findings.

TABLE 3-1 Recommended Breakpoints for Numbers of Organisms Identified Cytologically. Reported as Mean Number of Organisms per High-Dry Field (40× Objective)

Malassezia may also colonize the tympanic cavity, causing or contributing to otitis media. In one study, Malassezia was recovered from 65.8% of external ear canals and 34.2% of middle ears of dogs with chronic otitis.8 Yeast can be found mixed with bacteria; however, in the study by Cole et al,8 23.7% of dogs had otitis media associated with Malassezia infection alone. Malassezia is not a normal resident of the tympanic cavity; therefore, any finding on cytology from this space is considered abnormal, and systemic antifungal therapy is indicated.

Candida

Candida albicans is a normal resident of the skin and gastrointestinal (GI) tract of dogs and cats. Under appropriate circumstances, Candida can become an opportunistic pathogen. Compared with Malassezia, Candida spp. are not common pathogens in cases of otitis externa. In a study by Ginel et al,22 three of 24 dogs (12.5%), and two of 22 cats (9.1%) with clinical signs of otitis externa had cytologic and culture evidence of Candida spp. Cytologically, Candida are thin-walled, round to oval, and approximately 2 to 6 μm in diameter.23 A thin, clear capsule displaces stain and sediment, giving the appearance of a halo around the yeast body. The organism exhibits narrow-based budding and can form short, tubular, septate pseudohyphae. In contrast, Malassezia is unencapsulated, has broad-based budding, and never forms pseudohyphae or hyphae.

Bacteria

One of the primary uses of otic cytology is detection of the presence of bacteria. Unlike yeast, which can be readily identified using the 40× objective, proper evaluation for bacteria requires high magnification with an oil-immersion lens (100× objective, 1000× magnification). The diameter of most coccoid bacteria is typically 0.3 μm; coliform, rod bacteria are typically less than 1.5μm in length.24 In spite of this small size, and given quality equipment and practiced skill and ability, cytology can actually be more sensitive than culture for detecting bacteria.5,10 In one study of normal ear cytology, gram-positive cocci were identified in 42% of dogs by cytology but only 25% by culture. The actual percentage of normal patients with cytologic or culture evidence of bacteria may vary significantly based on geographic location and humidity. Ear conformation has not been shown to influence cytologic findings.10

Determining the significance of bacteria seen on cytology depends on several factors: morphology, numbers, and concurrent leukocytes. After bacteria have been identified, the clinician should determine whether there is a monoculture of a single morphologic type or whether a mixed infection is present, and then describe the morphology of bacteria seen. The presence of larger cocci arranged in pairs or tetrads is typical morphology for Staphylococcus spp; small cocci in short chains are characteristic of Streptococcus and Enterococcus spp. Even with these guidelines, laboratory culture is necessary to make a definitive speciation; clinicians should record findings as pairs of cocci or chains of cocci rather than attempt to make a specific diagnosis based on cytology. Corynebacterium is a large plump rod that may be found in normal or diseased ears. The most common rod-shaped pathogens associated with otitis externa are Pseudomonas spp. and Proteus spp. In tropical climates, coliform bacteria may be considered a normal finding. In more arid regions, only gram-positive cocci are commonly observed in normal patients.

In addition to morphology, the number of bacteria present should be estimated for each case. A semiquantitative cytologic criteria, similar to that proposed for Malassezia, can be used for bacteria (see Table 3-1). Based on the results reported by Ginel et al,22 fewer than five bacteria per high-powered dry field (40× objective) should be considered normal; more than 25 bacteria per field supports the diagnosis of an abnormally increased population. Using higher magnification, fewer than two bacteria per high-oil field (100× objective) is normal, and more than 10 bacteria per field is abnormal. For cats, fewer than four bacteria per 40× field (1.6 per 100× field) was consistent with normal conditions, and more than 15 bacteria per 40× field (6 per 100× field) was abnormal. Intermediate numbers in a gray zone are subject to interpretation. Using these mean-count breakpoints to differentiate normal from diseased ears yielded 95% specificity and 50% sensitivity in dogs, and 100% specificity and 63% sensitivity for cats.

Cytology, however, is not the only test that should be performed when evaluating bacterial otitis externa. Although cytology can demonstrate the presence, number, and relative significance of cocci or rods, it cannot be used to determine the species of bacteria. Bacterial culture is performed to identify species and determine the antimicrobial susceptibility of clinically relevant bacteria. Because culture does not differentiate between normal resident bacteria, bacterial overgrowth, and bacterial infection, cytology is the best tool to determine the relative significance of bacteria present in the external canal. Similarly, because culture does not accurately evaluate changes in numbers or the presence or absence of neutrophils, sequential bacterial cultures are not useful for monitoring response to therapy. Cytology is necessary to determine whether numbers of organisms are decreasing, if there is a change in the predominant organism, or if there is a change in the presence or absence of neutrophils. Bacterial culture in the absence of cytology is an inaccurate tool (Table 3-2).

TABLE 3-2 Comparison of Cytology and Culture for Evaluation of Otitis Externa

| ATTRIBUTE | CYTOLOGY | CULTURE |

|---|---|---|

| Time to available results | Immediate | 48–72 hours |

| Sensitivity for yeast | High | Low |

| Sensitivity for bacteria | High | Moderate to high |

| Sensitivity for leukocytes | High | None |

| Estimation of numbers | Semiquantitative | Categorical data |

| Rank significance in mixed infection | Yes | No |

| Monitor response to therapy | Yes | No |

| Detection of antimicrobial resistance | No | Yes |

When evaluating otitis media, a separate cytology should be performed from the tympanic cavity. Veterinarians should not assume that the same organism contaminates both sites. In a study comparing isolates from the horizontal canal and the tympanic cavity of dogs with chronic otitis externa and media, differences were noted in the species or antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria isolated in 89.5% of the cases.8 Therefore, samples for cytology and culture should be obtained from the tympanic cavity rather than the external canal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree