CHAPTER 5 Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Lesions

COLLECTION TECHNIQUES

Samples may be collected as fine-needle biopsies (FNB) (using either an aspiration or nonaspiration technique), scrapings, imprints, and/or swabs, depending on the characteristics of the lesion and the tractability of the patient. FNBs by an aspiration or a nonaspiration technique (see Chapter 1) are the standard method of collection because they yield the most representative and diagnostic samples in most situations. There are times, however, when alternate techniques or combinations of techniques are warranted, as discussed subsequently.

Fine-Needle Biopsies

Fine-needle biopsy is described in Chapter 1.

Solid Masses

Aspirates of Fluid-Filled Masses and Cysts

The lesion is prepared as solid masses are prepared (see Chapter 1). Using the blood smear, line smear, and/or squash prep technique(s) described in Chapter 1, smears can be prepared directly from the aspirated fluids or from the sediment of centrifuged fluids.

Scrapings

Scrapings of cutaneous lesions are made by rubbing the edge of a blunt instrument, such as a glass slide or the back of a scalpel blade, across the lesion. This results in an accumulation of cells along the edge of the blunt instrument. These cells are then spread onto a clean, dry, glass slide by one of the techniques described in Chapter 1.

Swabs

Other than for vaginal cytology (see Chapter 25), swabs are generally collected only when imprints, scrapings, and aspirates cannot be made (e.g., fistulous tracts). Swabbing (with a moist, sterile, cotton swab) the ulcerated surface of cutaneous lesions (especially neoplasms) often yields only surface inflammation. Sterile isotonic fluid, such as 0.9% NaCl, should be used to moisten the swab, although very moist lesions do not require that the swab be moistened. Moistening the swab helps minimize cell damage during sample collection and smear preparation. After sample collection, the swab is gently rolled along the flat surface of a clean, glass slide. (The swab should not be rubbed across the slide surface because this causes excessive cell damage.) If a hematologic-type stain is used (e.g., Wright’s), the smears are air-dried and stained as described in Chapter 1.

GENERAL APPEARANCE OF THE LESION

The general physical appearance of the lesion is helpful in interpreting the cytologic findings.

GENERAL EVALUATION OF CYTOLOGIC SMEARS

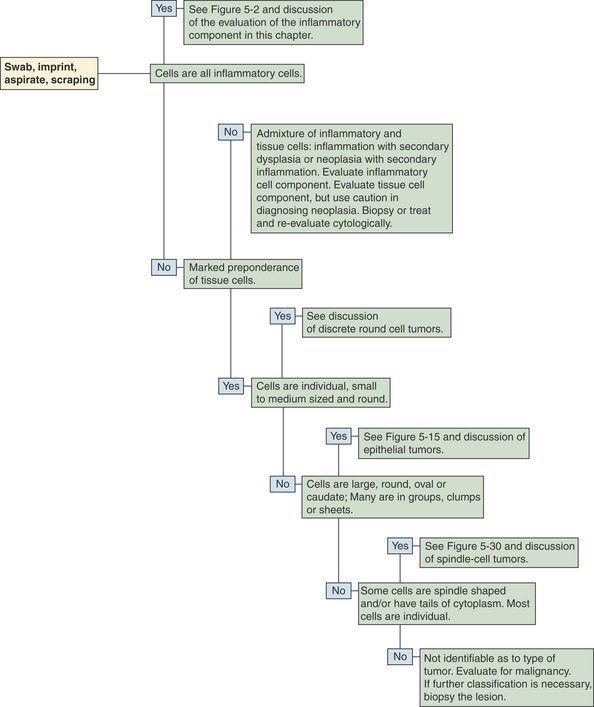

Once a suitable cytologic preparation is achieved, the number and type of cell populations present are determined. Smears are evaluated for evidence of inflammation and/or neoplasia (Figure 5-1). If all the cells from a solid mass are tissue cells (i.e., no inflammatory cells are present), the lesion is either due to neoplasia or hyperplasia or it was missed. If all the cells are inflammatory cells, an inflammatory process is occurring and is most likely the cause of the lesion, but an inflamed neoplasm cannot be ruled out. An admixture of inflammatory cells and dysplastic tissue cells can be caused by inflammation with secondary tissue cell dysplasia or neoplasia with secondary inflammation; therefore caution must be used in making the diagnosis of malignancy if evidence of inflammation is detected.

EVALUATION OF AN INFLAMMATORY CELL POPULATION

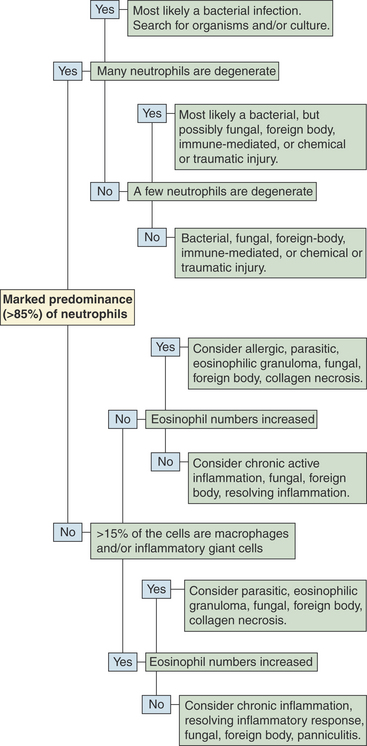

Figure 5-2 provides an algorithm to aid in the evaluation of the inflammatory cell component of cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions, and Table 5-1 gives general considerations for some inflammatory responses. If most of the inflammatory cells are neutrophils (see Figure 5-7 later in the chapter), especially when degenerate neutrophils are present, but no bacteria are found, a covert infection may be present, or the neutrophilic inflammatory response may be due to one of the conditions listed in Table 5-1 under “Marked predominance of neutrophils.” The lesion can be cultured to identify a covert infection. If the culture reveals an infectious agent, appropriate therapy can be instituted. If the culture does not reveal an infectious agent or if therapy for the infectious agent identified by culture is not effective, cytology can be repeated or a biopsy can be submitted for histopathologic evaluation.

Figure 5-2 An algorithm to aid in evaluating aspirates containing a preponderance of inflammatory cells.

Table 5-1 Some Conditions Suggested by Certain Proportions of Inflammatory Cells

| Inflammatory cell population | First considerations | Second considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Marked predominance (85%) of neutrophils | ||

| Many neutrophils are degenerate | Gram-negative bacteria Gram-positive bacteria | Abscess secondary to neoplasia, foreign bodies, etc. |

| A few neutrophils are degenerate | Gram-positive bacteria Gram-negative bacteria Higher bacteria (nocardia, Actinomyces, etc.) | Fungi Protozoa Foreign body Immune-mediated chemical or traumatic injury |

| No neutrophils are degenerate | Gram-positive bacteria Higher bacteria (nocardia, Actinomyces, etc.) Chemical or traumatic injury Panniculitis | Abscess secondary to neoplasia Gram-negative bacteria Fungi Foreign body Abscess secondary to neoplasia |

| Admixture of inflammatory cells | ||

| 15% to 40% macrophages | Higher bacteria (Nocardia, Actinomyces, etc.) Fungi Protozoa Neoplasia Foreign body Panniculitis Any resolving inflammatory lesion | Nonfilamentous gram-positive bacteria Parasites, chronic allergic inflammation and eosinophilic granuloma if eosinophil numbers are increased |

| >40% macrophages | Fungi Foreign body Protozoa Neoplasia Panniculitis Any resolving inflammatory lesion | Parasites, chronic allergic inflammation, and eosinophilic granuloma if eosinophil numbers are increased |

| Inflammatory giant cell present | Fungi Foreign body Protozoa Collagen necrosis Panniculitis Parasites (if eosinophils are present) | — |

| >10% eosinophils | Allergic inflammation Parasites Eosinophilic granuloma Collagen necrosis Mast cell tumor | Neoplasia Foreign body Hyphating fungi |

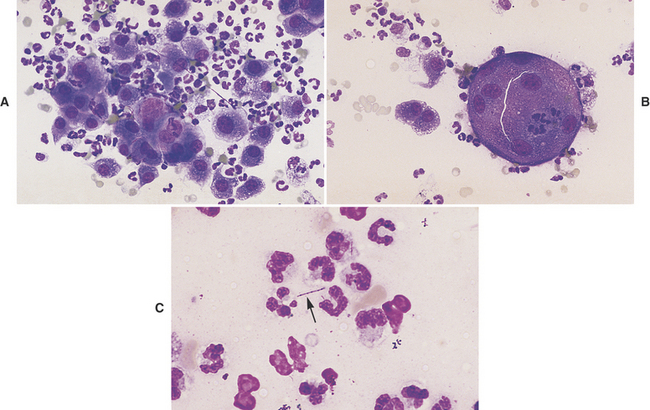

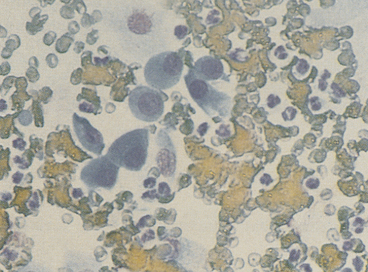

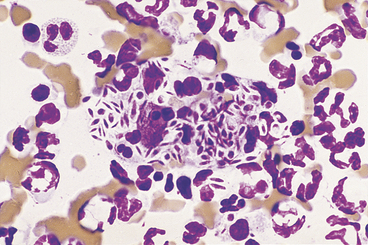

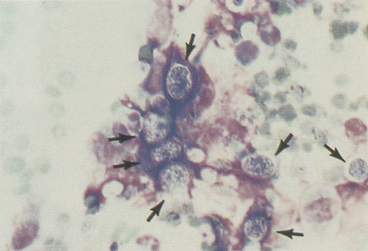

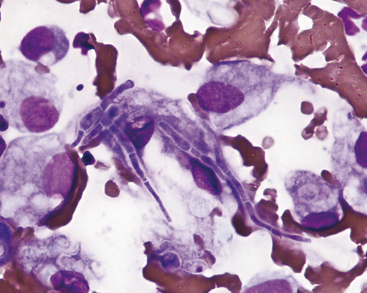

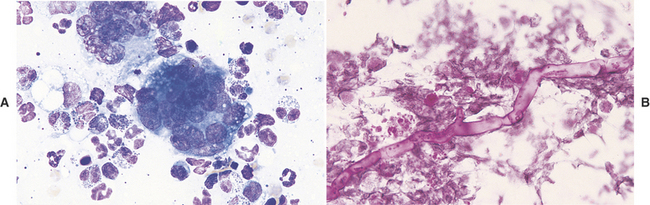

When >15% of the inflammatory cells present are macrophages (Figure 5-3, A), and/or inflammatory giant cells are present (Figure 5-3, B), fungal infection, infection with Actinomyces or Nocardia spp., foreign-body granuloma, or other causes of granulomatous inflammation (e.g., lick granuloma) should be considered. The slide should be carefully studied for organisms (Figure 5-3, C) or signs of a foreign body, such as refractile debris (Figure 5-4). Also, historical information about the possible introduction of foreign material should be sought. If no organisms are found and no historical information indicates the introduction of a foreign substance into the area, the tissue can be cultured, or a biopsy can be submitted for histopathologic examination.

If the proportion of eosinophils exceeds 10% (Figure 5-5), an allergic, parasitic, or foreign-body reaction or an eosinophilic granuloma complex lesion should be considered. The slide should again be carefully searched for organisms or signs of foreign material. If no organisms or signs are found, the lesion can be cultured (including fungal cultures), or a biopsy can be submitted for histopathologic evaluation. If the lesion is cultured, but not biopsied, and the culture fails to yield an organism, the lesion may be treated as an eosinophilic granuloma if the historical and clinical evidence is indicative of an eosinophilic granuloma complex lesion. In this situation, the lesion should be watched carefully. If the response to therapy is not appropriate, a biopsy of the lesion should be submitted for histopathologic evaluation.

When tissue cells showing criteria of malignancy are accompanied by inflammatory cells (Figure 5-6), the sample should be interpreted cautiously. Dysplasia occurring in tissue adjacent to inflammatory reactions can alter tissue cell morphology. As a result, tissue cells undergoing dysplasia in response to a local inflammatory process can be erroneously classified as neoplastic cells. As the intensity of the inflammatory reaction increases, the assurance with which a diagnosis of neoplasia can be made decreases.

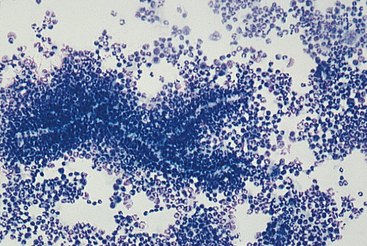

INFECTIOUS AGENTS

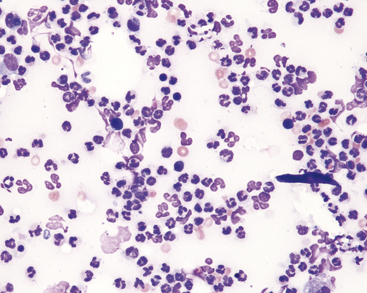

See Chapter 3 for more photographs of infectious agents. Infectious agents invariably cause lesions characterized by the presence of inflammatory cells. Bacterial agents usually produce lesions characterized by being composed of more than 85% neutrophils (Figure 5-7)—many of which may be degenerate. When bacteria are pathogenic, some can usually be found phagocytized within neutrophils in addition to those that may be present extracellularly. Mycotic agents produce lesions that tend to have more macrophages present than do bacterial lesions. However, neutrophils may still be the predominant cell type, and eosinophils may be plentiful with certain hyphating fungi. Cytologic evaluation often reveals the type of infectious agent (e.g., bacteria, yeast, protozoa) and in some cases yields a definitive diagnosis (e.g., histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis). Size, shape, staining characteristics, and internal structures are helpful in classifying the type of organism and in some cases, specific identification of the organism.

Bacteria

Bacterial Cocci

Pathogenic bacterial cocci (Figure 5-8) are usually gram positive and of the genera Staphylococcus or Streptococcus. Staphylococci usually occur in clusters of 4 to 12 bacteria, but Streptococcus spp. tend to occur in short or long chains of organisms. When cocci are identified in cytologic preparations, aerobic and anaerobic cultures and sensitivity tests should be performed to identify the organism and the optimum antibiotic therapy. Because most cocci are gram positive, antibiotic therapy effective against gram-positive organisms should be used when it is necessary to start therapy before culture and sensitivity results are received.

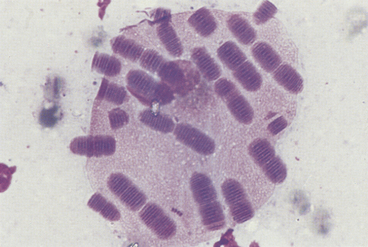

D. congolensis replicates by transverse and longitudinal division, producing long chains of coccoid bacterial doublets that resemble small, blue railroad tracks. It infects the superficial epidermis, causing crusty lesions. Cytologic preparations from the undersurface of scabs from these crusty lesions are most rewarding in demonstrating organisms. The preparations usually contain mature epithelial cells, keratin bars, debris, and organisms (Figure 5-9). A few neutrophils may also be found.

Small Bacterial Rods

Most small bacterial rods are gram negative. Some can be recognized as bipolar rods (Figure 5-10). All pathogenic, bipolar bacterial rods are gram negative. Infections with bacterial rods are usually associated with a marked neutrophilic inflammatory response. When small bacterial rods are recognized in cytologic preparations, the lesion should be cultured to identify the organism, and sensitivity tests should be performed to determine the optimum antibiotic therapy. If it is necessary to institute antibiotic therapy before the culture and sensitivity results are received, the therapy employed should be effective against gram-negative organisms because most pathogenic, small rods are gram negative.

Filamentous Rods

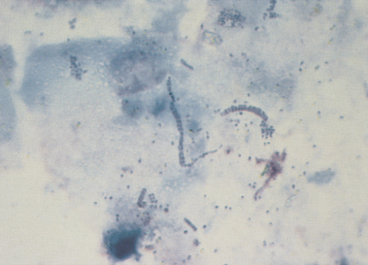

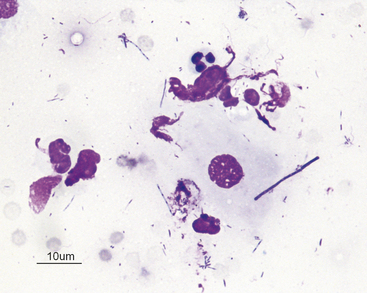

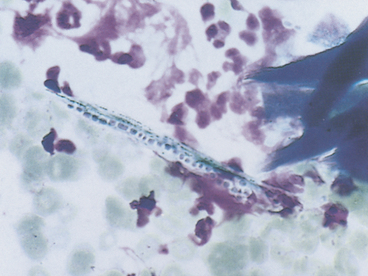

Pathogenic filamentous rods that cause cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions are usually Nocardia or Actinomyces spp. Some other anaerobes, such as Fusobacterium and Mycobacterium spp. may be filamentous, but rarely are. Nocardia and Actinomyces spp. are characterized by long, slender (filamentous) strands that stain pale blue and have intermittent, small, pink or purple areas (Figure 5-11; see Figure 5-3). This morphology is characteristic of both Nocardia and Actinomyces spp. and the filamentous form of Fusobacterium spp. When these features are recognized cytologically, cultures should be performed specifically for Nocardia and Actinomyces spp. and for other anaerobes.

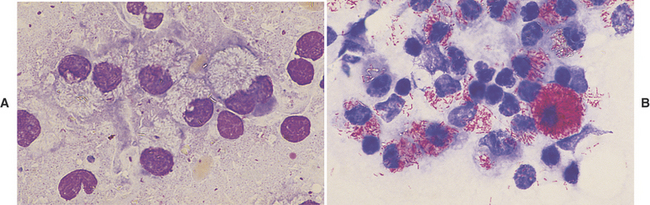

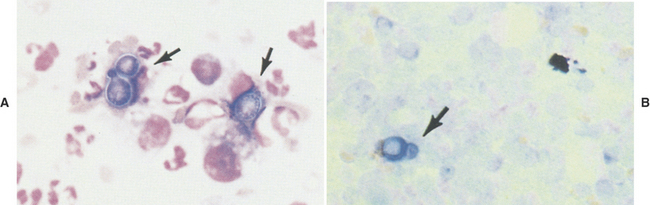

On the other hand, Mycobacterium spp. often do not stain with Romanowsky-type stains. As a result, negative images (Figure 5-12, A) may be observed in the cytoplasm of macrophages and/or inflammatory giant cells. When epithelioid macrophages and/or inflammatory giant cells are encountered in cytologic preparations that do not contain any obvious organisms, a careful search for negative images of Mycobacterium spp. should be made. Mycobacterium spp. stain with acid-fast stains; therefore when negative images are encountered, or when the character of the lesion suggests that Mycobacterium spp. be considered, an acid-fast stain can be performed to show the organism (Figure 5-12, B) and/or cultures for Mycobacterium spp. can be performed for identification.

Large Bacterial Rods

Large bacterial rods that are pathogenic and sometimes infect the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues include Clostridia spp., and infrequently, Bacillus spp. When large bacterial rods are thought to be pathogenic, both aerobic and anaerobic cultures should be performed. Also, the smears should be inspected for large rods containing spores (Figure 5-13). If spore formation is observed, Clostridium spp. is most likely present. Occasionally, extremely large nonpathogenic bacterial rods (Simonsiella) are observed in cytologic specimens (e.g., contaminated tracheal washes; Figure 5-14).

Yeast, Dermatophytes, Hyphating Fungi, and Algae

Sporothrix schenckii

In cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains, S. schenckii (Figure 5-15) are round to oval or fusiform (cigar-shaped). They are about 3 to 9 microns long and 1 to 3 microns wide and stain pale to medium blue with a slightly eccentric pink or purple nucleus. They may be confused with Histoplasma capsulatum if only a few organisms are found and they are not classically fusiform.

Histoplasma capsulatum

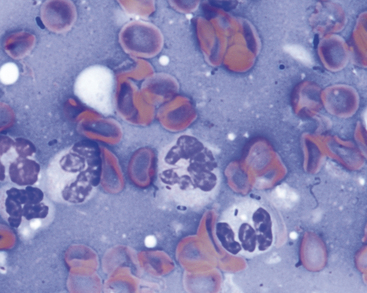

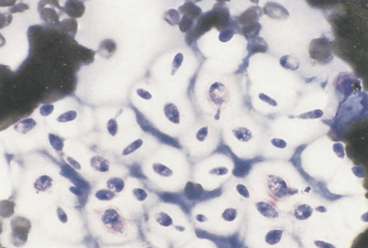

Although Histoplasma capsulatum usually infects the lungs and/or other internal organs, it can infect the skin, with or without concurrent involvement of internal organs. Cutaneous histoplasmosis lesions are typically raised and proliferative, and may ulcerate. On rare occasions, they may produce draining tracts. These lesions usually yield many organisms within macrophages and some extracellular organisms. A few organisms may be found in neutrophils. In cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains, H. capsulatum organisms (Figure 5-16) are round or slightly oval, but are not fusiform. They are about 2 to 4 microns in diameter (a fourth to half the size of a red blood cell [RBC]), stain pale to medium blue, and contain an eccentric pink to purple staining nucleus that is often crescent shaped. There is usually a clear halo around the yeast.

Blastomyces dermatitidis

A Blastomyces dermatitidis infection (blastomycosis) can involve the skin, eyes, and internal organs. Cutaneous lesions of blastomycosis are usually raised and proliferative, and often ulcerate. Cutaneous lesions should be sought when any form of blastomycosis is suspected. Aspirates from these lesions or impression smears of ulcerated lesions usually have a cell composition characteristic of pyogranulomatous inflammation (see Figure 5-3) and organisms ranging in number from a few to many. In cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains, the organisms (Figure 5-17) are blue, spherical, 8 to 20 microns in diameter, and thick-walled. Most organisms are single, but occasionally, organisms showing broad-based budding are found. These organisms are distinctly larger than S. schenckii or H. capsulatum and are differentiated from Cryptococcus neoformans by their color, lack of a clear-staining capsule, and broad-based budding. They are distinguished from Coccidioides immitis by their smaller size and lack of endospores.

Cryptococcus neoformans

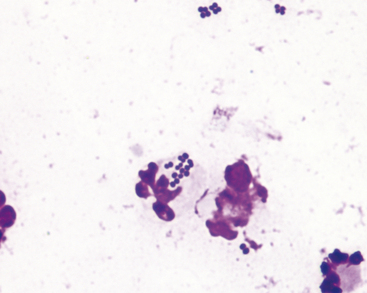

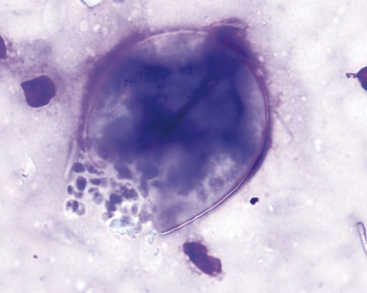

A Cryptococcus neoformans infection (cryptococcosis) can involve the subcutaneous tissues causing subcutaneous swellings, but more commonly involves the upper respiratory and central nervous systems. Cryptococcosis usually elicits a granulomatous response (epithelioid macrophages and/or inflammatory giant cells). In some cytologic preparations, Cryptococcus organisms may outnumber inflammatory and tissue cells. The organism (Figure 5-18) is extremely pleomorphic, ranging from spherical to fusiform, but usually is easily recognized because of its thick mucoid capsule. Occasionally, nonencapsulated, or rough, forms are found. The organism is about 4 to 15 microns in diameter without its capsule and about 8 to 40 microns in diameter with its capsule. In cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains, the organism stains deep pink to blue-purple and may be slightly granular. The capsule is usually clear and homogenous, but on some occasions, it may stain light to medium pink. Unlike Blastomyces spp., Cryptococcus spp. demonstrate narrow-based budding.

Coccidioides immitis

Coccidioides immitis infections generally involve the lungs and bones of dogs. In some cases, however, cutaneous lesions (masses) and draining tracts from bony lesions develop. Cytologic preparations usually have a cell composition characteristic of pyogranulomatous or granulomatous inflammation. Coccidioides organisms (Figure 5-20) may be scarce in some lesions; therefore cytologic preparations from suspected coccidioidomycosis lesions should be examined carefully. In cytologic preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains, the organisms are large (10 to 100 microns in diameter), double-contoured, blue or clear spheres with finely granular protoplasm and will often appear folded or crumpled. Round endospores from 2 to 5 microns in diameter may be seen in some of the larger organisms. The tremendous variation in the size and presence of endospores differentiates C. immitis from nonbudding B. dermatitidis.

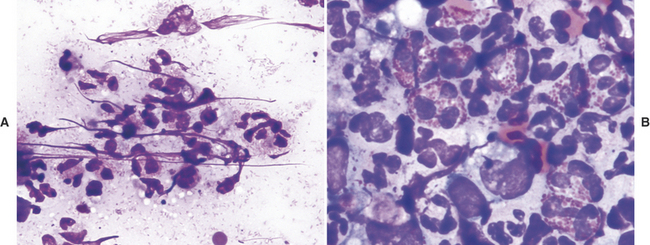

Dermatophytes

The dermatophytes Microsporum and Trichophyton spp. commonly cause ringworm in dogs and cats (Figure 5-21). Scrapings from the edge of lesions are the best cytologic samples for finding dermatophytes. They can be identified in cytologic preparations using the standard 10% potassium hydroxide stain for hair, in wet-mount preparations stained with new methylene blue, or air-dried preparations stained with Romanowsky-type stains. Cytologically, fungal mycelia and spores are found within hair shafts (Trichophyton spp.) or on the hair shaft surface (Microsporum spp.). With Romanowsky-type stains, the mycelia and spores stain medium to dark blue with a thin, clear halo. An inflammatory reaction of an admixture of neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells may be seen in cytologic preparations from skin scrapings.

Fungi That Form Hyphae in Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Tissues

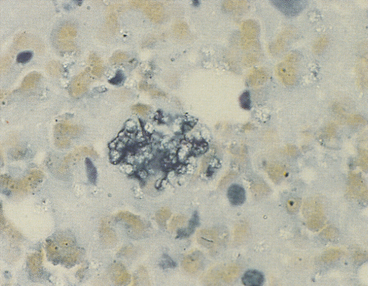

Many fungi can infect the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue and form hyphae (Figure 5-22). These fungi usually cause small to large raised, proliferative lesions that often ulcerate. They also induce a granulomatous, inflammatory response that is characterized by epithelioid macrophages and inflammatory giant cells (see Figure 5-3). The number of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils varies. Some hyphating fungi do not stain well with hematologic-type stains and are recognized as negative images (Figure 5-23). The organisms that cause the disease phycomycosis typically do not stain with hematologic stains and induce an eosinophilic, granulomatous response in the infected tissue (Figure 5-24). A fungal culture or histopathology with special immunohistochemical stains may be used to definitively classify the organism involved.

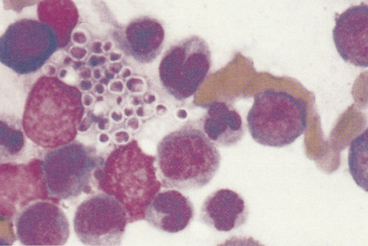

Prototheca zopfii and P. wickerhamii

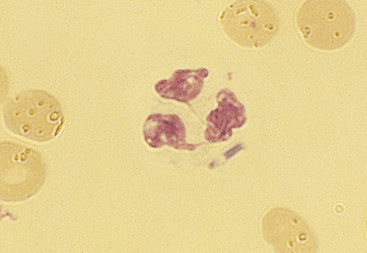

Prototheca spp. are colorless algae that are ubiquitous in the southern regions of America, but only rarely cause disease (i.e., protothecosis). In dogs, the disease is often disseminated, but only cutaneous protothecosis has been reported in cats.1–4 Cytologic preparations reveal an inflammatory response characteristic of pyogranulomatous or granulomatous inflammation and organisms ranging in number from a few to many. The organisms (Figure 5-19) are round to oval and are from 1 to 14 microns wide and 1 to 16 microns long. When stained with Romanowsky-type stains, they have granular basophilic cytoplasm and a clear cell wall about 0.5 micron thick. The organisms, except those that are small and immature, contain a small nucleus that stains pink to deep purple. A single organism may consist of two or four or more endospores. Most organisms are extracellular, but small forms may be found in macrophages and neutrophils.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree