Gregory J. Fleming †, Deidre K. Fontenot

Crocodilians (Crocodiles, Alligators, Caiman, Gharial)

Many of the 26 living crocodilian species are now endangered and are in need of both in situ and ex situ conservation programs. Because of this, crocodilians are more commonly being held in captive situations in conservation facilities, including zoos. Crocodilians are often long-lived display animals popular with zoo guests and require the skilled attention of veterinary and husbandry teams alike.

Anatomy and Physiologic Considerations

Respiratory System

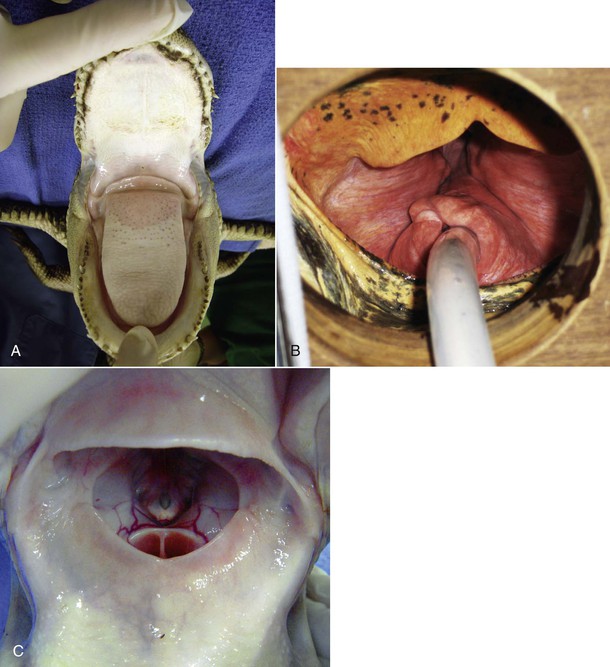

Crocodilians spend much of their time with their bodies entirely submerged with the exception of their eyes and nares. Each nostril acts as a water-proof valve that is closed with a muscular flap (composed of skeletal muscle) during submersion. In gharials (Gavialis gangeticus), the nasal opening has developed into a large protuberance, which acts as a vocal resonator.26 Closing the nares may be obtunded by immobilizing agents that relax the muscles of the nostril allowing water into the respiratory tract.6 An additional respiratory valve is formed by the soft palate and gular fold in crocodilians.20 The elongated soft palate (palatine flap) presses down against the dorsal flap of the tongue forming the gular valve. This seal allows the crocodilian to open its mouth underwater without water rushing into the internal nares and the glottis. The gular valve has to be displaced to visualize the glottis for endotracheal intubation (Figure 5-1). The glottis has two folds, and in most crocodilians, the trachea bends to the left (not in alligators) before bifurcation to allow for large pieces of prey to be swallowed.8,14 The lungs are well developed, and the vessel walls are thicker than in mammals to compensate for extra pressure during diving events. The primary respiratory muscle groups are the intercostal muscles and two transverse membranes, the postpulmonary membrane and the posthepatic membrane, both of which comprise primarily fibrous tissue with a muscular component.8 The postpulmonary membrane separates the lungs from the liver, and the posthepatic membrane is attached to a sheet of muscle that enters at the os pubis. These two membranes act as a diaphragm. They, along with other coelomic partitions, also make endoscopic visualization of coelomic organs difficult (Figure 5-2). Ventilation is achieved by expanding the intercostal muscles, and then membranes pull the liver in a caudal direction creating a negative pressure around the lungs. The lungs expand, and the air is drawn into the nostrils and into the lungs. The glottic valve is then closed, holding the air in the lungs. Once the glottic valve relaxes, air in the lungs is expelled passively via the elastic recoil of the intercostal muscles and the postpulmonary or posthepatic membranes and lung tissue.8 It is important to note that if the thoracic cavity is compressed, the animal cannot breathe. This may take place during restraint, as it is common to see multiple people sitting on the back of a crocodilian.

Cardiovascular System

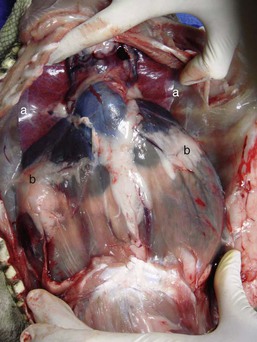

Crocodiles are the only reptiles that possess four-chambered hearts.16, 18 The heart functions like that of mammals; however, a number of anatomic differences allow for adaptation for an aquatic lifestyle. The three main differences are (1) a right aorta, which supplies the lungs, and a left aorta, which bypasses the lungs; (2) connective tissue extensions into the pulmonary outflow tract of the right ventricle, which restrict blood flow to the lungs (during diving) and allow a left to right shunt; and (3) the foramen of Panizza, an opening between the left and right aortic arches allowing pressure equalization during diastole. All work together to ensure supply of blood to the coronary and cephalic circulation during a complete shutdown of the left side of the heart, which might occur during prolonged dives.1,16,18

The foramen of Panizza is a small opening located between the interventricular septum at the confluence of the left and right aortic arches.16 This opening acts as a pressure valve allowing blood to flow between the venous and arterial systems. This flow from high pressure to low pressure results in venous admixture. When the animal is breathing, left ventricular pressure is greater, allowing a small amount of oxygenated blood to flow through the foramen of Panizza into the venous blood supply. When the crocodilian submerges, air held in the lungs restricts blood flow through the pulmonary capillary beds, resulting in pulmonary hypertension which increases right ventricular and pulmonary arterial pressures. As a result, blood flows from right to left through the foramen of Panizza.16 Deoxygenated blood is diverted away from the lungs through the left aortic arch to organs that are not sensitive to low levels of oxygen (e.g., liver and stomach).8 Oxygenated blood is diverted to oxygen-sensitive organs (i.e., the heart and the brain). A combination of blood shunting and anaerobic metabolism may allow an inactive crocodilian to stay submerged for 5 to 6 hours.14 This right-to-left shunt through the foramen of Panizza may have clinical implications during anesthesia when the crocodilian does not have ventilatory support or is apneic. Shunting of blood away from the lungs will delay inhalant anesthetic uptake and removal. This emphasizes the importance of assisted ventilation during any immobilization event.

Renal Portal System

Crocodilians possess a renal portal system composed of the renal portal vein arising from the epigastric and external iliac veins.16 These vessels drain blood from the dorsal body wall, the cloaca, the sex organs, and the bladder. Drugs injected into the caudal half of the body, base of the tail and hindlimbs, may be cleared by the kidneys prior to reaching the systemic circulation. In other reptile species such as the red-eared slider, studies have showed a significant hepatic first-pass effect following hindlimb drug administration.10 A study comparing forelimb and hindlimb injections of buprenorphine in red-eared sliders resulted in a 70% decrease in the bioavailability of buprenorphine when injected in the hindlimb.13 Additionally, it appears that opioids are highly susceptible to significant hepatic extraction in reptiles.8 Thus, care should be taken when administering nephrotoxic drugs in the hindlimbs, and when possible, anesthetic drugs should be injected in the forelimbs until further research is completed on crocodilian vascular anatomy.17 However, the author of this chapter routinely uses the tail base and the hindlimbs for intramuscular drug delivery for safety reasons, with no complications and desired effects.

Eyes

Crocodilians have three eyelids: the upper, the lower, and the third eyelid, the nictitating membrane, which is translucent and protects the eye during diving. The eye may also be retracted into the socket via a skeletal muscle during feeding, and the retina has a tapedum lucidum to assist with night vision.14

Ears

Bilateral ear openings, just caudal to the eyes on the top of the skull, are covered by a flap that closes during diving. Once past this flap, the tympanic membrane may be visualized; however, the opening is very small and it may difficult to open in an unanesthetized crocodilian. The eustachian tubes leave the inner ear and enter the pharynx just caudal of the internal nares.3, Inner ear infections are not common but may result in neurologic clinical signs such as spinning or rolling.

Skin

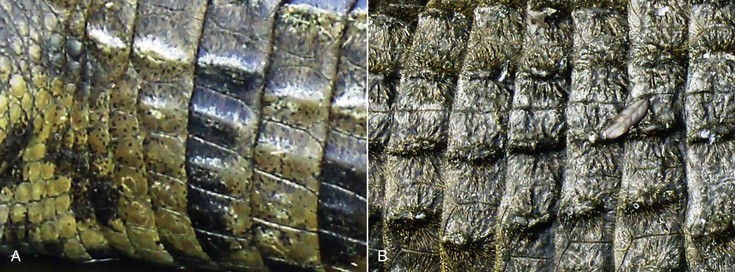

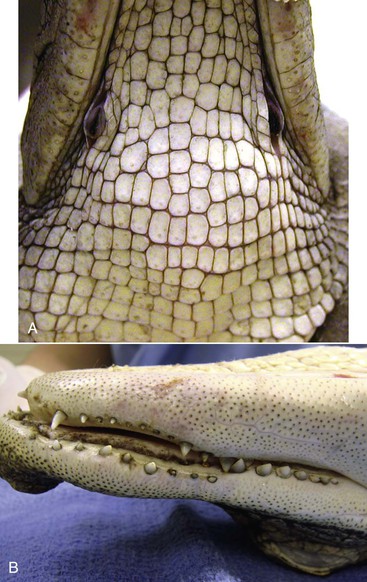

The skin of crocodilians contains both scales and scutes but no sweat glands. The dorsal scutes over the head and back contain bony plates, called osteoderms, which make darting or injecting challenging (Figure 5-3). Glandular secretions may occur from paired gular glands on the ventral mandible and some in the lips and cloaca in Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus), whereas Chinese alligators (Alligator sinensis) have rudimentary dorsal glands beneath the second to fifteenth rows of scales on the dorsum (Figure 5-4).14

Teeth

Crocodilians possess pointed conical teeth that are replaced over a crocodilian’s lifetime. This may occur as fast as every 3 to 4 months in juvenile American alligators and starts from back to front in alternate teeth in young animals and reverses in older animals. It appears that a certain number of replacements are available, as very old crocodilians with no teeth have been reported.4 Additionally, the two first positioned mandibular incisors may grow long enough to penetrate the upper maxilla in front of the nostrils. This is a normal anatomic development and does not cause any problem.

Husbandry

Crocodilians are poikilothermic, regulating their body temperatures by using external environmental heat sources. They also operate at a preferred optimal body temperature (POBT) similar to mammalian internal body temperatures. For captive crocodilians, a good range for environmental temperatures is 25° C to 35 ° C.5,8 Given a selection of temperatures, including a hot spot, crocodilians are able to select the POBT for their metabolic needs. Seasonal temperature fluctuations may result in a decrease or cessation of food consumption during winter months. It is common for species such as American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) and Nile crocodiles, in both the wild and outdoor holding in captivity (Florida), to stop feeding for 4 to 5 months during the winter months. Even crocodilians held indoors in heated enclosures may have reduced appetite during the winter months with decreasing temperatures and light cycles. Anorexia with temperatures in the POBT of 26° C to 32° C should be considered abnormal and warrants physical examination and diagnostic workup.

Temperatures below and above POBT interfere with digestion and immune function. American alligators take twice as long to digest food at 20° C than 28° C, whereas smooth-sided caimans digest food three times faster at 30° C than 15° C.8 Experimental infection of American alligators kept at 30° C demonstrated the greatest white blood cell (WBC) response to infection and survival of the infection, whereas alligators held above the POBT at 35° C succumbed to infection in 3 weeks.8 These investigations indicate that it is important to routinely evaluate captive crocodilian enclosures for a proper thermoenvironment to ensure good health. Thermoregulation has an important role during anesthetic events. Crocodilians under general anesthesia should be kept at temperatures near their POBT or around 29.5° C.8 Environmental temperatures below POBT decrease metabolism and thereby prolong clearance of injectable drugs, which results in delayed recoveries of up to days in length. Induction may also be prolonged because of slowed absorption and circulation times. For example, large Nile crocodiles induced with the neuromuscular blocker gallamine took twice as long to become recumbent at 14° C (40 minutes) than at 26° C (20 minutes).6

Enclosure Design

Water quality parameters for crocodilians should rival water quality in any aquarium system used for fish. Mechanical, biologic, and chemical filtration should be employed with routine testing of water quality parameters. Crocodilians may be able to handle poor water conditions for short periods, but this should not be the standard of care. In any crocodilian enclosure, clean water in the POBT with a dry, basking area is critical. The ability to dry off reduces the amount of superficial pathogens, through desiccation, and will also aid in achieving POBT through thermoregulation.

Most zoologic institutions have pairs or smaller groups of crocodilians living in one enclosure. However, in the case of housing numerous individuals in one enclosure, dominance and intraspecies aggression must be considered. In some species such as Chinese alligators, individual housing may be needed because of temperament issues. In group housing, a dominance order focusing on the prime feeding and basking areas will be established. In these cases, additional enclosure furniture such as trees or rocks may be used to “break up” sight lines. When designing exhibit pools, a number of smaller outpockets is recommended while limiting narrow passages to assist in reducing territorial establishments and restricting the movements of other animals in the enclosure (Figure 5-5).

Pica and consumption of rocks or other objects is a common behavior of crocodilians. In necropsies preformed on wild Nile crocodilians, gastroliths, small rocks, up to 5 centimeters (cm) in size, is a normal finding (Hofmyer M, personal communication, 2011). Often, captive crocodiles may consume inappropriate objects to satisfy this behavior. Gastroliths are usually nonpathogenic and are often found during routine examination or during radiography. Small rocks do not cause medical issues and may be an incidental finding. Larger rocks less than 20 cm, pieces of PVC pipe, life support system components, coins, and metal foreign bodies may be of greater concern and require removal. In the case of metal objects such as coins, heavy metal toxicity, for example, zinc or lead toxicity, should be investigated. Removal of larger or irregular objects may be accomplished under general anesthesia with endoscopy. Small objects or coins may be removed simply via gastric lavage. Stomach lavage may be completed under general anesthesia, with the crocodilian intubated. In large crocodilians, a 1.5-meter (m) long, 7-cm diameter PVC pipe may be fashioned with an equine stomach tube taped to the PVC pipe. This set up may then be lubricated and inserted via the esophagus into the stomach. The pipe is typically palpable externally on the left side of the crocodile, and the smell coming out of the pipe should be acidic and typical of crocodilian ingesta. Flushing large amounts of water down the equine stomach tube with the animal’s head angled down may displace smaller stomach content by allowing it to drain out through the PVC pipe. In a second technique, a homemade scoop with a long handle may be inserted into the stomach and used to scoop out stomach contents.

Nutrition

In the wild, crocodilians are opportunistic carnivorous feeders, ranging from juveniles consuming small invertebrates and fish to large adults eating whole ruminants. In captivity, diets often consist of small to medium vertebrates and sometimes larger prey items. Prey items should be of high quality and not decomposed and are usually defrosted prior to feeding. Defrosting may be accomplished by placing the frozen item in a fridge 24 hours prior to feeding, which allows the food item to thaw but does not allow bacterial colonization and decomposition to start. Alternatively, in the case of smaller prey items such as mice, the frozen animal may be placed in a bucket of warm to hot water and defrosted in less than 30 minutes and then fed to the crocodilians. This does not allow for decomposition to set in and provides a warmed food item.

Whole Prey

Whole prey items (including organ tissue) from crickets to large vertebrates are the most common food source for crocodilians. Whole prey items are easy to manage, as they may be stored for months in a freezer. Frozen prey items should not be stored for longer than 3 months because of the nutritional breakdown of antioxidants such as vitamin E and other vitamins and minerals (Valdes E, personal communication, 2013). Many species of white fish (e.g., herring) have enteric thiaminase, which breaks down vitamin B1. Thiaminase is not inactivated by freezing and thus continues to break down vitamin B in frozen fish. The longer the fish is frozen, the less vitamin B is available, which may result in hypovitaminosis B that leads to immune suppression and neurologic disease. Crocodilians fed a fish diet (caimans and gharials) may need to be supplemented with vitamins or other whole prey items, and frozen fish stocks should be rotated on a monthly schedule to reduce the buildup of thiaminase in frozen fish. Supplements such as calcium and mineral powders used to dust insects prior to feeding should be stored in a freezer. Refrigeration or freezing provides a more stable environment; however, supplements should be kept for no longer than 6 months. Studies have shown that storage of supplements in environments with fluctuating temperatures results in a fast degeneration of vitamins and minerals (Valdes E, personal communication, 2013).

Prepared Food Items

Prey items that have been skinned or have had the organ tissue removed are not considered whole prey items. In some institutions, feeding nutria (Myocastor coypu) that were skinned and the organs removed resulted in clinical signs of tooth loss, mandibular swelling, and reduced tooth replacement. Hypovitaminosis A and E, as well as high whole blood lead levels from lead shot found in the carcasses of the nutria, were noted in these reports. Crocodilians recovered with proper diet (pelleted and commercial meat product) and treatments with vitamin E and A supplements (retinyl palmitate and alpha-tocopherol (Heard D, personal communication, 2011).

Commercial Pelleted Diet

Alligator farms have been feeding pelleted diets for many years and zoos may offer similar diets as well. Pelleted diets are accepted by most species of crocodilians with reports of gharials being the exception. When feeding pelleted diets, it is easy to overfeed and cause obesity. Pelleted diets are concentrated nutritionally because of low water content. Whole prey items contain about one third of the caloric density (per kilogram, of food based on a dry-matter basis [DMB]) compared with a pelleted diet. For example, if a crocodilian is normally fed a diet of whole prey items (i.e., 9 kg per week), the animal would only need to be fed one third of 9 kg (3 kg of pellets) a week to achieve the same caloric intake. If the same weight amount in pellets were fed as whole prey, the crocodilians would be receiving a 200% increase in diet, which would result in obesity (Valdes E, personal communication, 2013).

Feeding guidelines may be highly variable and influenced by such factors as species, nutritional ecology, individual health status, nutritional goals (growth, maintenance, or weight loss), training plans, and environmental temperatures. As a general guideline for adult crocodilians, at mean feeding temperatures of 26° C to 37° C, the chapter author recommends feeding at a rate of 3.25 kilocalories per kilogram (kcal/kg) body weight (BW) (i.e., 600–1000 kcal/day for an adult Nile or American crocodile) providing protein at 60% to 65% on a DMB with energy at 5.5 to 5.82 kcal/g diet DMB, calcium at 1.93% to 2.4% DMB, and phosphorus at 1.39% to 1.92% DMB. An example diet for a monthly schedule with one diet item per week would include chicken (bones, skin, and no feathers), whole quail, crocodilian biscuit or pellet, whole tilapia, whole rabbits, whole rats, and herring. Juvenile diets are similar in composition (protein at 50% DMB, energy 6 to 6.1 kcal/g diet DMB, calcium at 1.38% to 2.4% DMB, and phosphorus at 1.28% to 1.38% DMB) but offer higher feeding rates at 8% BW per week (197 kcal/week, 840 kcal/month, average 28 kcal/day) or 19.3 kcal/kg BW with amount fed reevaluated frequently on the basis of the body condition score (BCS) and growth goals. Juvenile diets may also include smaller items such as prawns, lake smelt, mouse pinky or fuzzy, aquatic gel diets, insects (crickets or mealworms dusted with mineral supplements), and trout pellets (Valdes E, personal communication, 2013).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree