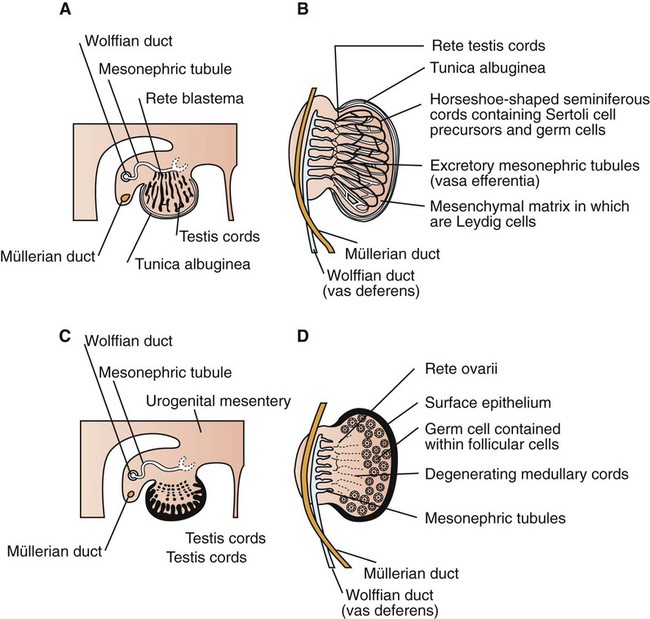

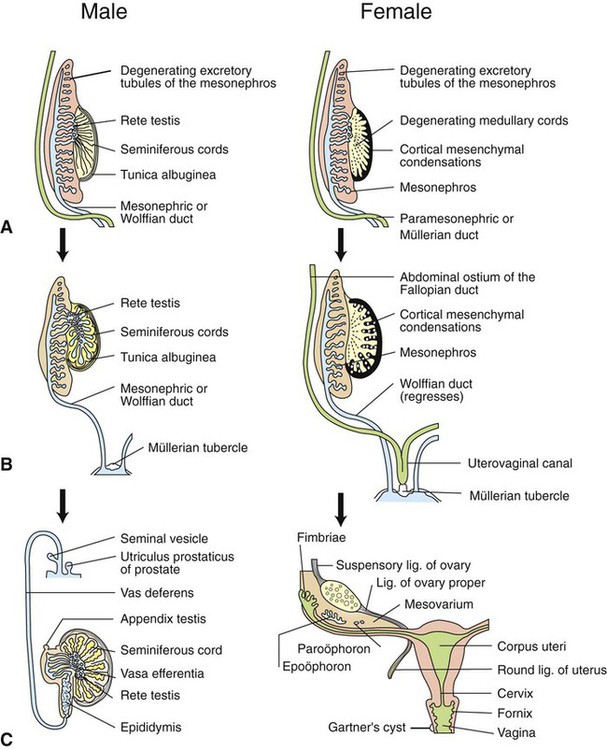

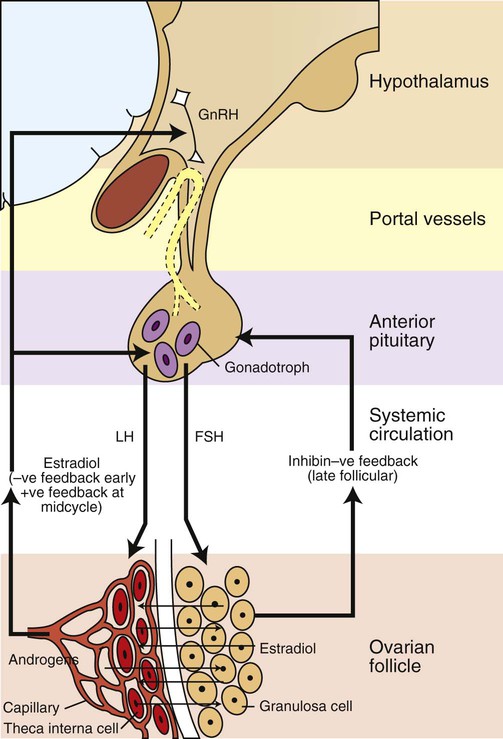

Development of the reproductive system 1. Organization of the gonads is under genetic control (genetic sexual differentiation). 2. Sexual organization of the genitalia and brain depends on the presence or absence of testosterone. Hypothalamopituitary control of reproduction 1. The hypothalamus and anterior pituitary (adenohypophysis) secrete protein and peptide hormones, which control gonadal activity. 2. The adenohypophysis (pars distalis) produces follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and prolactin, all of which control reproductive processes. Modification of gonadotropin release 1. The pulsatile release of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) induces the critical pulsatile production of the gonadotropins, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). 2. Gonadotropin release is then modulated by the process of negative feedback from estrogen and progesterone. 1. Gamete development occurs initially without gonadotropin support and subsequently with pulsatile gonadotropin secretion. 2. In the preantral follicle, gonadotropin receptors for luteinizing hormone develop on the theca, which results in androgen synthesis; follicle-stimulating hormone directs the granulosa to transform the androgens to estrogens. 3. Late in the ovarian follicular phase, luteinizing hormone receptors develop on the granulosa, which permits the preovulatory surge of luteinizing hormone to cause ovulation. The development of the embryonic testis is similar to that of the ovary: germ cells migrate into the genital ridge and populate sex cords that have formed from an invagination of the surface (coelomic) epithelium (Figure 35-1). Sertoli cells (male counterparts of granulosa cells) develop from the sex cords, and Leydig cells (male counterparts of thecal cells) develop from the mesenchyme of the genital ridge. One fundamental difference from ovarian development is that the invagination of the sex cords in the male continues into the medulla of the embryonic gonad, where connections are made with medullary cords from the mesonephros (primitive kidney). The duct of the mesonephros (wolffian duct) becomes the epididymis, vas deferens, and urethra, which has a direct connection to the seminiferous tubules. Thus, male germ cells pass to the exterior of the animal through a closed tubular system. The development of the genital tubular system and the external genitalia (genital sexual differentiation) is under the control of the developing gonad. If the individual is female—that is, the developing gonad is an ovary—the müllerian duct develops into oviduct, uterus, cervix, and vagina, whereas the wolffian duct regresses; the absence of testosterone is important for both changes (Figure 35-2). If the individual is male, the rete testis produces müllerian-inhibiting factor, which causes regression of the müllerian ducts. The wolffian duct is maintained in the male because of the influence of androgens produced by the testis. To summarize, the müllerian ducts are permanent structures, and the wolffian ducts are temporary structures unless acted on by the presence of male hormones. The presence of an enzyme, 5α-reductase, is important for the effect of the androgens because testosterone must be converted intracellularly into dihydrotestosterone for masculinization of the tissues to occur. The use of synthetic 5α-reductase inhibitors for the treatment of benign prostatic disease in humans is contraindicated without concurrent birth control measures, because drug levels in semen deposited in the female can lead to disorders of sexual development in male fetuses. Gonadal activity is under the control of both the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary gland (Figure 35-3). The hypothalamus lies near the ventral midline of the diencephalon. It is divided into halves by the third ventricle and actually forms the ventral and lateral walls of the third ventricle. The hypothalamus has clusters of neurons, collectively called nuclei, which secrete peptide hormones important for controlling pituitary activity. As described in more detail later, these peptides move to the pituitary either directly by passage through the axons of neurons or by a vascular portal system. The pituitary responds to the hypothalamic peptides to produce hormones that are important for the control of the gonads.

Control of Gonadal and Gamete Development

Development of the Reproductive System

Organization of the Gonads Is Under Genetic Control (Genetic Sexual Differentiation)

Sexual Orientation of the Genitalia and Brain Depends on the Presence or Absence of Testosterone

Hypothalamopituitary Control of Reproduction

The Hypothalamus and Anterior Pituitary (Adenohypophysis) Secrete Protein and Peptide Hormones, Which Control Gonadal Activity

The Adenohypophysis (Pars Distalis) Produces Follicle-Stimulating Hormone, Luteinizing Hormone, and Prolactin, All of Which Control Reproductive Processes

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree