10 Congenital/developmental diseases

Primary skin disorders innewborn foals

Epitheliogenesis imperfecta(aplasia cutis; cutaneous agenesis)

Generalized primary seborrhoea

Congenital curly coat syndrome

Albinism/lethal white foal syndrome

Fell pony immunocompromise disorder

Congenital equine cutaneous mastocytosis

7Congenital vascular hamartoma/cavernoushaemangioma

Secondary skin disorders innewborn foals

Ulcerative dermatitis, thrombocytopeniaand neutropenia syndrome

Primary congenital/hereditary conditionsin older foals and adults

Linear keratosis/linear alopecia

Hereditary equine regional dermal asthenia(HERDA; hyperelastosis cutis/cutaneousasthenia/Ehlers–Danlos syndrome/dermatosparaxis)

Hypotrichosis/mane and tail dystrophy(follicular dysplasia)

Arabian fading syndrome (pinky Arabsyndrome)

The breeding implications always need to be considered when a foal is presented with serious congenital abnormalities. Where breeding programmes are monitored closely it may be possible to draw conclusions about the merit or otherwise of rebreeding either the mare or the stallion or both. The Fell pony immunodeficiency syndrome has prominent primary cutaneous signs but the inherent immunocompromise means that secondary cutaneous infections are often present. Since the disease is an established autosomal recessive, the mare and the stallion should be removed from the breeding population immediately on the grounds that they must both be heterozygous recessive carriers. However, where a homozygous dominant stallion can be identified, it is sometimes justifiable to allow breeding to carrier mares. Whilst this clearly has implications for the dissemination of the disease gene, no foals will be affected by the syndrome and gradually the population will be biased towards dominant (non-carrier) animals. This therefore can be viewed as a justifiable first step in a control programme. However, the reality is that little is known about most of the conditions and so little advice can be given with confidence.

When a neonatal foal is presented with skin disease, the clinician needs to take account of all the available possibilities because some are cutaneous manifestations of systemic disease. For example, a young foal with a severe cutaneous infection with Dermatophilus congolensis may be immunocompromised and the earliest sign of the Fell pony syndrome is a russet-coloured, long coarse coat.

PRIMARY SKIN DISORDERS IN NEWBORN FOALS

Epitheliogenesis imperfecta (aplasia cutis; cutaneous agenesis)

Profile

This is a rare congenital, inherited cutaneous defect of foals. Possibly a single autosomal recessive gene is responsible, at least in American Saddlebred horses (Scott 1988a, Stannard 1994a, Lieto & Cothran 2003).

There is a complete or partial absence of one or more of the dermal components including the epidermis, dermis, subcutis and fat (Scott 1988b). Although defects on the limbs are probably more common, the body trunk and hooves, and even the tongue and proximal oesophagus may also be affected.

Many of the previous reports of this condition can be attributed to epidermolysis bullosa (see p. 232) rather than cutaneous agenesis (Scott & Miller 2003a).

Clinical signs

Clearly demarcated solitary or regional areas with a complete absence of epidermis and skin appendages are present at birth (Fig. 10.1). The extent of the skin defect may be less severe than the subcutaneous adhesion problems. The commonest and most obvious defects occur distal to carpus and tarsus but it can be over much larger areas. Dermal adhesion in the adjacent tissues can be severely affected and in some cases the defect can be extensive. The margins of the defect are noticeably free of inflammation (Fig. CD10 • 1) .

.

The tongue and the proximal oesophagus can be affected also. Severely affected foals may be aborted.

Differential diagnosis

• Epidermolysis bullosa: a very rare vesico-bullous condition associated with a dermo-epidermal fragility so that the skin can be rubbed off the affected areas; largely restricted to the Belgian breed but can occur in other breeds and donkeys.

Key points: Epitheliogenesis imperfecta

Key points: Epitheliogenesis imperfecta

• Hereditary equine regional dermal asthenia (HERDA): cutaneous adhesion disorder that is restricted largely to Quarterhorses and manifest by skin fragility and lack of elasticity. Signs are usually delayed until the skin is subjected to trauma from harness and weight-bearing. Wounds that result from skin necrosis are very slow to heal and may not do so or may result in severe disfiguring scars.

• Obstetric trauma/trauma/savaging or predation: history of dystocia or overt evidence of trauma.

Epidermolysis bullosa

Profile

This is a very rare complex group of heritable junctional mechanobullous diseases occurring principally in the Belgian and Saddlebred breed of both sexes, characterized by fragile ‘blister’ formation on the skin and oral mucosa, following mild trauma (Kohn et al 1985, Scott 1988a, Stannard 1994a). Other breeds and donkeys are sporadically affected. Although the human condition carries the same name and there are some similarities, there is limited information on how this relates to the equine condition (Linder 2000).

The junctional form of the condition is the most common form and probably results from a lamina lucida defect (Berthelsen & Eriksson 1935, Lieto et al 2002). Variations in location of the clefting within the epidermis are theoretically interesting but have no material significance for the management of the condition. It has been suggested that some of the previous reports of cutaneous agenesis in foals may in fact have been epidermolysis bullosa and so the condition may be slightly more common.

Clinical signs

Lesions at mucocutaneous junctions and oral mucosa and elsewhere are visible at birth (Fig. 10.2). Further lesions develop shortly afterwards. Collapsed bullae may be found in the mouth, and separation of hooves at the coronary band is sometimes present and foals have sloughed the hoof capsule within hours or days of birth (Frame et al 1988).

Concurrent dystrophic teeth commonly occur.

Differential diagnosis

• Epitheliogenesis imperfecta: overt deficits of skin cover present at birth over various localized or more general regions in the complete absence of any traumatic cause.

Key points: Epitheliogenesis bullosa

Key points: Epitheliogenesis bullosa

• Hereditary equine regional dermal asthenia: usually manifest much later in life.

• Systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome.

Diagnosis

• Few other conditions are realistically similar.

• Some breed relationships (Belgian/Standardbred).

• Histopathology shows characteristic cleavage and bulla formation at the epidermal–dermal junction.

• Positive Nikolsky’s sign (transverse finger pressure does cause the epidermis to ‘slip’ off the underlying dermis).

Generalized primary seborrhoea

Clinical signs

At birth the foal is usually normal but in the first 6–12 months of life, the coat becomes greasy and staring. The normal patina of horse skin is lost (Fig. 10.3).

Figure 10.3 This foal was diagnosed with primary seborrhoea from birth.

Figure courtesy of Dr Marianne Sloet.

Key points: Generalized primary seborrhoea

Key points: Generalized primary seborrhoea

1. A rare congenital disorder of epidermal cell hyper-proliferation with inappropriate sebum production.

2. Generalized greasy scale and flake occur over the whole body from a young age. Secondary bacterial and Malassezia spp. infection is common.

3. Diagnosis is only made when the condition has been present from birth or shortly afterwards and when it affects the whole body and causes of secondary seborrhoea have been eliminated. Biopsy is largely unrewarding with non-specific epidermal hyperplasia and hypertrophy and excessive scale.

4. Treatment is palliative/symptomatic with degreasing and descaling shampoos.

5. The prognosis for the animal is good but the skin requires long-term management.

Differential diagnosis

• Secondary seborrhoea (see p. 459p. 459): usually a result of other chronic skin infections/insults.

• Hypothyroidism: extremely rare and associated with hair and skin thinning with goitre development.

• Neonatal pemphigus foliaceus: very rare, generalized, immune-mediated vesico-bullous, seborrhoeic condition with coronary band and chestnut margin involvement; histology may be typical (see p. 266).

Congenital curly coat syndrome

Profile

Defined genetic lines are possibly more susceptible and the trait appears to be a dominant gene. Currently there is a move towards recognition of the curly-coated horse as a specific breed (Scott 2004).

Clinical signs

Foals are born with an abnormally long, curly hair coat that remains until the adult hair grows through and in some cases the condition remains (Fig. 10.4). The main and tail are also affected. The extent of curliness is very variable. The mane and tail can be affected alone (‘wavy-mane syndrome’) but it can also affect the whole body surface. The winter coat is often a more tightly curled ‘ringlet-like’ pattern while the summer coat is smoother but with prominent ‘waves’.

There may be variable degrees of alopecia with coat and mane and tail thinning (hypotrichosis) especially in the summer coat. The tail is often badly affected and may lose almost all its hair, giving the horse a rat-tailed appearance (termed ‘string tail’).

Key points: Congenital curly coat syndrome

Key points: Congenital curly coat syndrome

1. A congenital disorder mainly affecting Paint horses. This is sometimes viewed as a desirable trait and so active steps are taken to maintain the condition in some breeds and lines within breeds.

2. A prominent curly, dense coat is present from birth and develops into a dense, wavy coat quality. The condition may be restricted to the mane and tail (wavy mane syndrome) but can affect the whole body. Some hair loss is also often present including the tail and mane.

3. Diagnosis is based on the characteristic features and the breeding history.

4. Treatment is not usually requested and in any case there is none!

5. The condition has no apparent deleterious effect on the horse and neither is it associated with any other congenital defect and so the prognosis is irrelevant.

Diagnostic confirmation

• Breed line related (owners will usually recognize it immediately). The signs appear to be the same for winter and summer coats.

• Histological evidence can be derived from body and mane/tail biopsy (Scott 2004) but the histological signs are subtle (Scott & Miller 2003b). Follicular dysplasia appears to be the most characteristic histological feature.

Albinism/lethal white foal syndrome

Profile

Key points: Albinism/lethal white foal syndrome

Key points: Albinism/lethal white foal syndrome

1. Albinism is an incidental condition that affects ponies more than horses. Affected animals have a white or pink skin (cf. grey horses which have a black or dark skin). The lethal white syndrome is an important and highly fatal disorder mainly affecting foals with Overo-Paint breeding.

2. Albinism does not, in itself, have any disease implication for the horse although the lack of pigment may make the skin more sensitive to sunlight and so actinic dermatitis and squamous cell carcinoma may be more prevalent.

3. The lethal white syndrome is characterized by a severe non-responsive neonatal colic associated with either an atretic (incomplete) gastrointestinal tract or ileus resulting from aganglionosis or both.

4. Diagnosis of albinism is simple. Diagnosis of lethal white syndrome is based on the very typical clinical signs and breeding history.

5. There is no treatment for either condition. Albinotic horses probably need to be given extra sun-protection (mask for face and eyes and light rugs) but most seem to cope well anyway. Lethal white foals must be destroyed immediately; any attempts to restore normal gut function will fail.

Lethal white foal syndrome occurs with the mating of Overo and Paint horses of the pinto breed and is an autosomal recessive trait. This is an inherited condition. Cases have been encountered in other breeds also (Lightbody 2002). Affected foals are white (albinos) but frequently have concurrent, highly fatal defects of the gastrointestinal tracts such as atresia ani, atresia coli and in particular ileocolonic aganglionosis (Knottenbelt & Pascoe 1994, Stannard 1994a). The pathogenesis of the condition appears to be linked to the gene that controls endothelin metabolism.

Clinical signs

Partial albino horses are relatively common, showing pink skin and a white hair coat (Fig. 10.5A). The retina is invariably partially or completely albinotic and the iris may be variously pale blue or white in colour (either completely or partially). Possibly the greatest implication for these animals is their liability to actinic dermatitis (sunburn) and squamous cell carcinoma. Many also have degrees of photophobia and light-related retinal damage can occur.

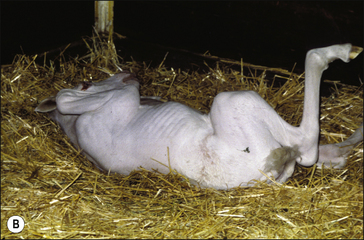

Lethal white foals are a startlingly white colour at birth (Fig. 10.5B); a few have small faint brownish tinges particularly on their ears. Although they may be apparently normal for the first 1–2 hours after birth, they rapidly develop severe intractable and fatal colic as a result of an incomplete intestinal tract or ileus as a result of intestinal aganglionosis (or both). Concurrent abnormalities of the mouth, pharynx, heart or other structures are also sometimes present.

Differential diagnosis (lethal white syndrome only)

• Neonatal ischaemic hypoxic syndrome (neonatal maladjustment)/cerebral trauma at or during birth: these foals are not usually showing colic signs but are genuinely seizuring.

• Idiopathic/benign epilepsy: genuine seizures without colic and not related to colour or breeding.

• Cerebellar/cerebral hypoplasia syndromes: cerebellar ataxia and hypermetria with intention tremors.

• Extensive blood loss at or during birth (visible or invisible) including early cord separation: obvious and usually profound anaemia.

Diagnostic confirmation (lethal white syndrome only)

• Characteristic colour and abrupt onset of associated clinical syndromes of colic and/or intractable seizures.

• Arterial oxygen normal and no evidence of parturient hypoxia.

• Normal haematology/biochemistry.

• Cerebrospinal fluid and electroencephalograms are normal.

• Post-mortem examination will identify concurrent developmental abnormalities and intestinal aganglionosis.

Lavender foal syndrome

Profile

Key points: Lavender foal syndrome

Key points: Lavender foal syndrome

1. A recently described, genetically based coat colour dilution syndrome mainly seen in Arabian horses and their crosses.

2. Prominent neurological symptoms are present from birth and the affected animal usually fails to stand. Convulsions, blindness and opisthotonus are present.

3. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs alone – laboratory features are non-specific and rather disappointing.

4. There is no treatment – the condition is fatal.

5. Parents of the affected foal should probably not be used for breeding but little is known about the syndrome as yet.

Clinical signs

‘Lavender foals’ have a characteristic lavender (bluish/purple) coat colour at birth (Fig. 10.6). The skin is actually normal and there is no dermatological implication. The colour is simply a visible indicator of a critical (lethal) neurological disorder. Affected foals are neurologically abnormal from birth, showing neonatal seizures and convulsions (often even occurring during or immediately after birth). Opisthotonus, paddling, aimless galloping while recumbent and apparent blindness with a light-hungry and startled expression may be present. No periods of remission or sleep occur. Affected foals fail to rise and have no (or reduced/abnormal) suckle reflexes. Death is inevitable.

Differential diagnosis

• Neonatal-hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy/cerebral trauma at or during birth: convulsions are similar but biochemical tests and blood gas analysis can be used to confirm the conditions; no coat colour relationship.

• Idiopathic/benign epilepsy: no colour relationship and seizures are intermittent and predictable with prodromal and post-ictic signs.

• Cerebellar/cerebral hypoplasia/abiotrophy syndromes: coarse movements and intention tremors but otherwise bright and alert; mainly Arabian foals.

• Extensive blood loss at or during birth (visible or invisible) including early cord separation: overt anaemia and history of blood loss.

Diagnostic confirmation

• Characteristic colour and abrupt intractable seizures.

• Most cases of lavender foal syndrome show no detectable lesions in any organ, suggesting that it is a functional/physiological neurological disorder with skin colour alterations.

• Arterial oxygen is normal and there is usually no evidence of parturient hypoxia.

• Normal haematology/biochemistry.

• Cerebrospinal fluid and electroencephalograms are normal.

• Post-mortem examination will identify concurrent developmental abnormalities and intestinal aganglionosis.

Fell pony immunocompromise disorder

Profile

This condition is a recently described disorder affecting pure bred Fell pony foals under 16 weeks of age (Scholes et al 1988, Richards et al 2000, Butler et al 2006). Severe immunocompromise as a result of a T-cell malfunction with a simple recessive gene is involved. The condition is not similar to any of the other major immunocompromising disorders of foals.

Clinical signs

Diarrhoea and failure to thrive as well as increasing lethargy are common. A progressive microcytic, normochromic anaemia is a universal feature (Fig. 10.7).

The condition is invariably fatal before 12 weeks of age.

Key points: Fell pony immunocompromise disorder

Key points: Fell pony immunocompromise disorder

1. A specific inherited autosomal recessive immunocompromising disorder affecting Fell pony foals under 12–14 weeks of age.

2. Cardinal early signs include a russet halo of long coarse hairs and progressive non-regenerative anaemia. Opportunistic infections including those of the skin are frequently encountered. Other signs include diarrhoea, poor growth and weight gain and oral, respiratory and intestinal infections.

3. Diagnosis is based on breeding history and on the typical signs – usually anaemia is taken as an early indicator.

4. Treatment attempts are fruitless – the condition is 100% fatal.

5. Neither parent of an affected foal should be used for breeding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree