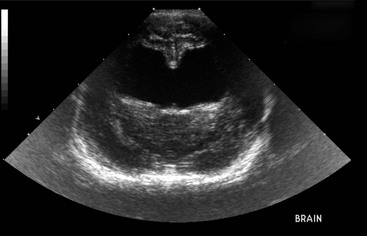

Chapter 225 Hydrocephalus is active distention of the ventricular system of the brain caused by obstruction of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from its point of production to its point of absorption (Rekate, 2009). CSF is produced at a constant rate by the choroid plexuses of the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles; the ependymal lining of the ventricular system; and blood vessels in the subarachnoid space. The CSF circulates through the ventricular system into the subarachnoid space, where it is absorbed by arachnoid villi. Obstruction can be caused by developmental abnormalities or acquired lesions such as neoplasia or inflammatory lesions. Early hydrocephalus initially damages the ependymal lining of the ventricles. This allows water and larger molecules to leak into the adjacent white matter, causing periventricular edema. Further enlargement of the ventricles compresses the white matter, which leads to demyelination and axonal degeneration. The septum pellucidum separating the lateral ventricles can become fenestrated or completely destroyed, so that one single, large ventricle is created (Figure 225-1). In some cases, the cerebral cortex is preserved. In more severe cases, the cortex becomes thin, with neuronal vacuolation and loss of neurons. This affects the prognosis after surgical shunting. If the cortex is preserved, shunting results in reexpansion of the white matter and regeneration of remaining axons. However, if the cortex is damaged, the neuronal damage persists even after shunting. With severe obstruction to CSF flow, the volume of CSF can increase so fast that it causes an increase in intracranial pressure, which leads to further brain damage and impairs blood flow to the brain. In pediatric patients with persistent fontanelles, ultrasonography allows easy detection of obviously enlarged ventricles. Normal-sized ventricles appear as paired, slitlike anechoic structures just ventral to the longitudinal fissure on either side of the midline. Enlarged ventricles are seen easily as paired anechoic regions. With marked ventricular enlargement, the septum pellucidum that normally separates the lateral ventricles is absent and the ventricles appear as a single, large anechoic structure (Figure 225-2). Figure 225-2 Transverse ultrasound performed through the fontanelle. The lateral ventricles are evident as a single large anechoic structure.

Congenital Hydrocephalus

Causes

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree