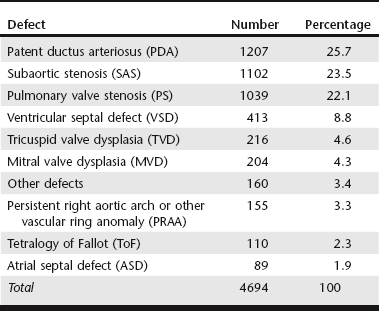

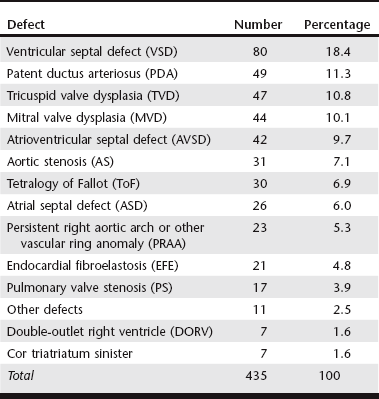

Chapter 174 In the dog, persistent patency of the ductus arteriosus (see Web Chapter 64), pulmonary valve stenosis (see Web Chapter 65), and subaortic stenosis (see Web Chapter 66) are the most common forms of CHD. In the cat, ventricular septal defect (see Web Chapter 69) appears to be the most common form of CHD encountered. In both species, less commonly observed defects include atrial septal defect, mitral valve dysplasia (see Web Chapter 62), tricuspid valve dysplasia (see Web Chapter 68), atrioventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, vascular ring anomalies, and peritoneal-pericardial diaphragmatic hernia, among others. The prevalence of CHD in the dog and cat is difficult to quantify due to a lack of routine perinatal care, occurrence of conditions that are not apparent on routine physical examination, and hospital biases in published reports. The work of Detweiler and Patterson in the Philadelphia area suggested a CHD prevalence rate of 0.56% among 4831 dogs surveyed in the mid-twentieth century (Detweiler and Patterson, 1965), whereas Buchanan found a rate of 0.67% for all dogs brought to the University of Pennsylvania between 1987 and 1989 (Buchanan, 1992). In a study of 1679 puppies aged 6 to 18 weeks at a pet store, murmurs were observed in 11, which suggests an incidence of CHD of 0.66% (Ruble and Hird, 1993). However, this may be an underestimation because it fails to include those puppies that died from CHD before the age of 6 weeks or those animals whose disease was silent to auscultation at that age. Conversely, this study may have overestimated the incidence of CHD because further testing was not performed to determine if the murmur was reflective of true CHD or simply functional or physiologic in origin. Additionally, the pet store population is likely biased toward purebred dogs, which are known to carry a higher proportion of hereditary defects than mixed-breed dogs. Although the true prevalence of CHD in dogs and cats is unknown, data are available that indicate the relative incidence of specific malformations in each species. In an attempt to compile these data, several studies of CHD prevalence were analyzed and the data were combined (Tables 174-1 and 174-2). Ten applicable studies of CHD prevalence in dogs were found in the veterinary literature, comprising a sum of 4694 defects (see Table 174-1). When the defects were totaled, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (25.7%), subaortic stenosis (SAS) (23.5%), and pulmonary valve stenosis (PS) (22.1%) were found to be the most common and of nearly equal incidence, together comprising almost three fourths of all instances of CHD in the dog. Defects in the ventricular septum (8.8%) and atrial septum (1.9%) accounted for an additional 10.7% of cases, whereas dysplasias of the mitral valve (4.3%) and tricuspid valve (4.6%) were present in nearly equal frequency. The constellation of defects known as tetralogy of Fallot (ToF) accounted for 2.3% of defects, whereas more complex lesions not easily classified into the aforementioned categories made up 3.4% of CHD. Not all studies provided data on vascular ring anomalies, which may present with noncardiac signs and therefore likely are underrepresented in these data. TABLE 174-1 Congenital Heart Disease in Dogs Combined data from Patterson DF: Epidemiologic and genetic studies of congenital heart disease in the dog, Circ Res 23:171, 1968; Mulvihill JJ, Priester WA: Congenital heart disease in dogs: epidemiologic similarities to man, Teratology 7:73, 1973; Hunt GB, Church DB, Malik R: A retrospective analysis of congenital cardiac anomalies (1977-1989), Aust Vet Pract 20:70,1990; Buchanan JW. Causes and prevalence of cardiovascular disease. In Kirk RW, Bonagura JD, editors: Current veterinary therapy XI: small animal practice, Philadelphia, 1992, Saunders, p 647; Tidholm A: Retrospective study of congenital heart defects in 151 dogs, J Small Anim Pract 38:94, 1997; Kittleson MD: The approach to the patient with cardiac disease. In Kittleson MD, Kienle RD, editors: Small animal cardiovascular medicine, St Louis, 1998, Mosby, p 195; Buchanan JW: Prevalence of cardiovascular disorders. In Fox PR, Sisson DD, Moise NS, editors: Textbook of canine and feline cardiology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1999, Saunders, p 458; Baumgartner C, Glaus TM: Congenital cardiac diseases in dogs: a retrospective analysis, Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 145:527, 2003; Gregori T et al: Congenital heart defects in dogs: a double retrospective study on cases from University of Parma and University of Zaragoza, Ann Fac Medic Vet di Parma 28:79, 2008; Oliveira P et al: Retrospective review of congenital heart disease in 976 dogs, J Vet Intern Med 25:477, 2011. TABLE 174-2 Congenital Heart Disease in Cats Combined data from Liu SK: Pathology of feline heart diseases, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 7:323, 1977; Harpster N, Zook B: The cardiovascular system. In Holzworth J, editor: Diseases of the cat: medicine and surgery, Philadelphia, 1987, Saunders, p 820; Hunt GB, Church DB, Malik R: A retrospective analysis of congenital cardiac anomalies (1977-1989), Aust Vet Pract 20:70, 1990; Kittleson MD: The approach to the patient with cardiac disease. In Kittleson MD, Kienle RD, editors: Small animal cardiovascular medicine, St Louis, 1998, Mosby, p 195; Michaelsson M, Ho SY: Congenital heart malformations in mammals, London, 2000, Imperial College Press. Fewer data are available about CHD prevalence in the cat. Table 174-2 compiles CHD cases from five studies to provide cumulative data on 435 defects. Ventricular septal defect (VSD) appears to be the most common defect in the cat, comprising over 18% of cases. PDA is not considered a common defect in the cat, compared with the dog, but accounted for over 11% of defects tabulated in these studies. Mitral valve dysplasia (MVD) and tricuspid valve dysplasia (TVD) each accounted for an additional 10% of defects. Abnormalities of the atrioventricular septum (AVSDs; formerly known as endocardial cushion defects or atrioventricular canal defects) are not infrequent in the cat, comprising a tenth of the cases reported. However, not all studies clearly defined the location of tabulated atrial septal defects (ASDs) and VSDs, nor fully described the morphology of diagnoses of MVD and TVD—all of which may be forms of AVSD. For this reason, the proportion of at least partial AVSDs is likely higher than tabulated here. Earlier studies described a high proportion of endocardial fibroelastosis in kittens, particularly the Burmese and Siamese breeds, but this disease was not described in more recent studies. Compared with dogs, abnormalities of the outflow tracts (PS and SAS) appear much less common in cats. There are few studies evaluating the use of cTnI as a biomarker in animals with CHD. A mild elevation (median, 0.20 ng/ml; range, 0.20 to 1.29) was shown in 30% of dogs with PS before balloon valvuloplasty (Saunders et al, 2009b). However, a study by a different group found normal cTnI values (≤0.05 ng/ml) in dogs with PDA and PS before intervention (Shih et al, 2009). Based on these limited data, cTnI level does not appear to be a reliable screening test for CHD in animals, although further studies are needed. More data are available to suggest that NT-proBNP levels are elevated in dogs with CHD. A study by Saunders and colleagues (2009a) found median NT-proBNP values of 724 pmol/L (range, 50 to 3000) in dogs with PDA, 746 pmol/L (range, 278 to 3000) in dogs with PS, and 833 pmol/L (range, 388 to 2194) in dogs with ASD compared with 333 pmol/L (range, 161 to 826) in normal dogs. Also in 2009, Farace and colleagues found that NT-proBNP values in dogs with SAS were elevated and correlated with the severity of the stenosis: normal dogs had a mean NT-proBNP level of 361 pmol/L (range, 307 to 415), dogs with mild SAS had a level of 344 pmol/L (range, 239 to 448), dogs with moderate SAS showed a level of 1011 pmol/L (range, 86 to 1936), and those with severe SAS had a level of 2529 pmol/L (range, 1841 to 3217). Although NT-proBNP level does appear to have some usefulness in determining the presence or absence of CHD, it cannot distinguish the type of defect present. More comprehensive studies are needed to better define the value of NT-proBNP in screening young animals for the presence of CHD.

Congenital Heart Disease

Prevalence

Diagnostic Testing

Congenital Heart Disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree