Chapter 1 Congenital disorders

Introduction

Congenital ocular defects are considered elsewhere (Chapter 8), as are umbilical hernia (2.9), cryptorchidism (10.18), pseudohermaphroditism (10.40–10.42), and cerebellar hypoplasia (4.1, 4.2).

Cleft lip (“harelip”, cheilognathoschisis); cleft palate (palatoschisis)

Clinical features

two obvious cranial abnormalities are illustrated here. A cleft lip in a young Shorthorn calf is shown in 1.1, in which a deep groove extends obliquely across the upper lip, nasolabial plate and jaw, involving not only skin but also bone (maxilla). This calf had extreme difficulty in sucking milk from the dam without considerable loss through regurgitation.

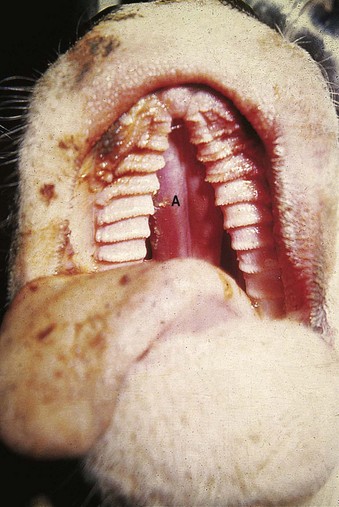

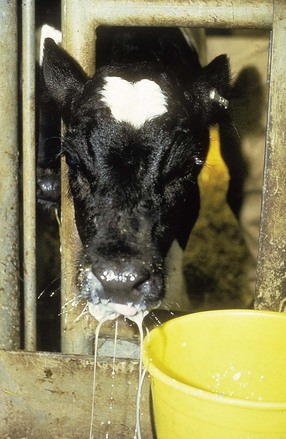

Cleft palate is seen as a congenital fissure of varying width in both the hard and soft palates of neonatal calves (1.2). The nasal turbinates (A) can be clearly seen through the fissure. The major presenting sign is nasal regurgitation, as seen in the Friesian calf (1.3). An aspiration pneumonia often develops early in life from inhalation of milk, sometimes while still nursing. Some calves with smaller fissures may appear clinically normal during suckling because the teat when in the calf’s mouth, closes the fissure. Clinical signs are seen when it starts to eat solid food. Cleft palate is often associated with other congenital defects, particularly arthrogryposis (1.15). The Holstein calf (1.2) was a “bulldog” (see 1.6). Other midline defects include spina bifida (1.20) and ventricular septal defect (1.30, 1.31).

Meningocele

The large, red, fluid-filled sac (1.4) is the meninges protruding through a midline cleft in the frontal bones. The sac contains cerebrospinal fluid. The calf, a 4-day-old Hereford crossbred bull, was otherwise healthy. An inherited defect was unlikely in this case (see also 1.20).

Salivary mucocele

Clinical features

this Limousin x Friesian heifer (1.5) had shown this soft, painless, fluctuating swelling since birth. In other cases it develops in the first few weeks of life.

Achondroplastic dwarfism (“bulldog calf”) or dyschondroplasia

Clinical features

the Hereford calf (1.6) demonstrates brachycephalic dwarfism. The head is short and abnormally broad, the lower jaw is overshot, and the legs are very short. The abdomen was also enlarged. The calf had difficulty in standing, was dyspneic as a result of the skull deformity (“snorter dwarf”), and a cleft palate was also present. A 2-week-old Simmental crossbred suckler calf (1.7) shows severe bowing of all four legs, especially forelegs, stunting, and a slightly dished face, and euthanasia was indicated. Born in May from a winter-housed dam fed only silage, extra feed appeared to reduce the incidence of achondroplasia from 40/200 to 5/200 offspring in successive years.

Bulldog calves are often born dead (1.8). This Ayrshire has a large head and short legs, but also has extensive subcutaneous edema (anasarca). Dwarfism is inherited in several breeds, including Hereford and Angus.

A related condition is congenital joint laxity and dwarfism (CJLD), which is a distinct congenital anomaly in Canada and the UK. A severe CJLD case from Canada, the newborn calf (1.9) has a crouched appearance, short legs, metacarpophalangeal hyperextension, and sickle-shaped hind legs. Many calves are disproportionate dwarfs. The joints become stable within 2 weeks and the calves can then walk normally. Other abnormalities are not seen. In the UK in 2009/10, 70 of a group of 85 South Devon x Angus calves showed shortened limbs, joint laxity (especially of the fetlocks), dyspnea in the first days of life, and in a few cases brachygnathia. The dams had been fed straw after housing, and later straw and silage.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree