• Mild cases can potentially survive and live without significant airway problems. • In more severe cases surgical correction is generally undertaken in multiple stages. This type of reconstructive surgery is expensive and requires significant aftercare. Although the objective of the surgery is usually to make the horse capable of being an athlete, unfortunately, neither the functional nor cosmetic outcome can be guaranteed. • Sub-epiglottic cysts. Endoscopy is essential for diagnosis. Make sure that swallowing is observed during endoscopy to allow observation of the ventral aspect of the epiglottis and the caudal aspect of the soft palate. Cysts located in the sub-epiglottic tissue may not always be visible while the epiglottis is in its natural position relative to the soft palate, being located under the rostral palatine border. Oroscopic examination may be required for diagnosis. • Pharyngeal cysts. These are not directly visible endoscopically, but symmetric or asymmetric dorsal pharyngeal compression, which is not attributable to guttural pouch enlargement, is visible and lateral radiographs of the pharynx confirm their presence. • Concurrent developmental defects of the epiglottis are sometimes present and these influence the clinical effects and endoscopic and radiographic appearance. • Repeated dorsal displacement of the soft palate may be present, possibly as a result of inadequate free rostral length or inadequate stiffness of the epiglottis. • Surgical intervention will be warranted. Surgical resection via a ventral midline laryngotomy works best but with smaller cysts laser ablation may suffice. • The clinical appearance is typical. Skull radiographs are diagnostic, but endoscopy will confirm involvement of one or both ostia. The free borders of the ostia are often slightly curled in these cases, and noticeably fail to open effectively during the low-pressure (second) phase of swallowing, as the larynx is lowered. • If in doubt as to the involvement of one or both pouches, air can be released from one pouch by either placing a blunt probe through the ostia on one side or aspirating air percutaneously on one side. If this results in complete resolution of the swelling then only one pouch is affected. • For severe cases of pharyngeal collapse the use of a tracheostomy will be warranted. • For unilateral tympany a fenestration through the median septum is achieved either via endoscopic-guided laser or blunt dissection via a hypovertebrotomy incision which will allow the egress of trapped air from the tympanitic pouch through the normal side. • With bilateral involvement transendoscopic laser fenestration of the septum or fistulation into the guttural pouch through the pharyngeal recess avoids a surgical incision and the risk of nerve damage. • The diagnosis of tracheal stenosis and collapse is based on signalment, history, clinical signs and endoscopic and radiographic findings. • No significant treatments plans have been implemented to increase the success of surgical options. The prognosis is usually good for life but poor for athletic functions. • Passage of a nasogastric tube will be obstructed at the pharynx. Endoscopic examination will reveal the obstruction in the posterior nares. • Immediate tracheostomy is warranted during respiratory distress. Surgical intervention has been described with the prognosis for athletic performance being described as poor. • The clinical appearance of the branchial cysts may be very similar to guttural pouch tympany and enlarged retropharyngeal lymph nodes. Endoscopic examination may reveal collapse of the dorsal pharyngeal wall and compression of the ipsilateral compartment of the guttural pouch. • Ultrasound examination reveals an anechoic fluid-filled structure with a well-defined hyperechoic capsule. Aspiration of the cysts reveals an amber viscous fluid with a high protein and a low cellularity (lymphocytes and macrophages). Radiographs reveal a large space-occupying soft tissue mass. • Medical management would consist of marsupialization and iodine sclerotherapy. Surgical excision may be necessary for larger cysts. • Radiographically, fluid-filled structures, with multiple air–fluid interfaces, soft tissue mineralization and gross deviations of the nasal septum are characteristic. Dental distortions and nasal cavity occlusion may be evident endoscopically. • Frontonasal flap surgery is generally effective. Facial deformity may resolve in young horses following surgery. • They may be difficult to differentiate from maxillary cysts but, radiographically, gas–fluid interfaces are not usually present. • Facial deformity is often marked and, as most occur in the rostral maxillary sinus, facial swelling over the third and fourth cheek teeth in foals up to 6 months of age is suggestive of the presence of a mucocele. • This is a rare condition and as such few treatment options are well described, but surgical creation of an effective naso-maxillary opening is a possibility. • Complete evaluation of the extent of defects can only be performed during exploratory surgery or necropsy, but the condition can be suspected on the basis of a combination of palpation, endoscopy and radiology. • When the upper esophageal sphincter is absent, lateral radiographs reveal a continuous column of air extending from the pharynx into the esophagus. • There is no effective treatment although laser treatment of rostrally displaced palatopharyngeal arch has been described but affected individuals make poor athletes. • Nasal cavity. Those lodged in the nasal cavity result in a unilateral nasal discharge of acute onset, often with small amounts of fresh blood. Affected horses show considerable discomfort, being head-shy and snorting a great deal. Sneezing is unusual in the horse under any circumstances. Untreated cases may result in local abscesses or the development of mineralized concretions within the nasal cavity and a foul-smelling breath from the affected nostril. • Pharynx. Acute-onset dysphagia with complete or partial respiratory obstruction. Large solid objects such as pieces of apple would be expected to have marked effects upon respiration, particularly on inspiration and the effects are consequently dramatic and of peracute onset. In most cases these are transient with the object dislodging spontaneously and resolution is immediate and complete. In some cases, however, the object appears to be firmly lodged and a life-threatening respiratory obstruction may be presented. Horses which habitually chew wooden fences and doors are also liable to pharyngeal obstructions as a result of pieces of wood breaking off. Sharp, small foreign bodies present little immediate threat to life and do not often cause respiratory embarrassment. However, an acute onset of severe and distressing difficulties with swallowing is frequently presented. The affected horse presents with nasal regurgitation of food material and saliva and attempts to drink are accompanied by nasal regurgitation and expressions of pain such as squealing and arching of the neck. Occasionally unilateral (or in some cases bilateral) epistaxis is present. • Trachea. The inhalation of small grass seeds and particles of dust and grass is common when horses are exercised hard under appropriate conditions. These seldom cause any marked effect and coughing is usually sufficient to dislodge the foreign matter. A residual tracheitis may be present for a day or two thereafter. Plant twigs represent a relatively common tracheal foreign body and are often responsible for an acute onset of a severe and frequently paroxysmal coughing. Tracheal hemorrhage is usual and there is often some inflammation and reflex spasm of the airway. • Endoscopy is usually required for diagnosis even in cases of nasal foreign bodies. In some longstanding cases the foreign body itself may be difficult to identify due to the level of inflammation or secondary infection. • Removal of the foreign body is the primary goal of treatment followed by treatment of secondary inflammation and infections if present. • In many instances it may be impossible to remove the foreign body whole without causing further damage and in these cases it may be necessary to break up the foreign body using endoscopic tools. • Injuries involving the sinuses or the nasal turbinate bones are usually accompanied by slight, moderate or heavy bleeding from the ipsilateral nostril. Even considerable nasal bleeding seldom seems to result in marked distress. • The immediate consequences of such injuries are related primarily to the bleeding and to any consequent nasal edema and swelling. Sufficient damage to result in an effective occlusion of both nostrils is very rare, even in cases with gross facial damage. • Damage to the nasolacrimal duct may result in occlusion leading to epiphora. • Sinus empyema, involving either of the maxillary sinuses and/or the frontal sinuses, represents a serious complication of failure of drainage and infection following traumatic injuries to the face. • The extent of any fractures may be defined by careful lateral and appropriate oblique radiographs. Most fractures are non-displaced and in such cases identification of the fracture site may be difficult if there are no external indicators. • Evidence of caudal maxillary (and frontal) sinus involvement can be obtained from endoscopic examination of the common drainage pathway of these sinuses in the caudal nasal cavity. • Treatment depends on the site of the trauma and the involved structures. • Endoscopy is normally sufficient for a diagnosis although some cases may mimic laryngeal hemiplegia. Additional findings which are variably present include ulceration, granuloma formation, necrosis and cavitation of the arytenoid cartilage, sinus tracts, deformity of the corniculate process or kissing lesion on the contralateral cartilage. • Medical therapy is normally attempted primarily depending on the level of deformity present. This includes rest, antibiotics and anti-inflammatories. Throat sprays and nebulization are also useful and hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been used in some cases with anecdotal reports of success. • In cases in which medical therapy does not give satisfactory results surgical options can be considered. Transendoscopic laser debulking is recommended for horses with granuloma formation. Partial, complete or subtotal arytenoidectomy may be performed depending on the individual case. • Subcutaneous emphysema which can readily be identified as a non-painful crackling under the skin. • Stridor may occur but is not consistently present. • Bilateral hemorrhagic nasal discharge may or may not be present. • Tachypnea secondary to pneumomediastinum. • Complicating infection of the original wound or of the emphysematous tissues (particularly where this is due to gas-producing bacteria such as Clostridium spp.) results in a similar appearance, but the difference is clinically obvious, with severe inflammation, pain and reluctance to swallow or bend the neck. • Tracheoscopy is needed for confirmation of the tracheal laceration. Thoracic radiography can aid in the diagnosis of secondary pneumomediastinum • Small tears may form a fibrin seal rapidly within 24–48 hours. Larger tears should be treated promptly (see below) to avoid infection, obstruction from peritracheal tissue and progression of subcutaneous emphysema to pneumomediastinum with resultant pneumothorax. • A temporary tracheostomy distal to the site of tracheal perforation may have to be performed in cases where a large tracheal laceration has occurred. This procedure diverts air away from the site of tracheal injury, helping restore airway control by decreasing the subcutaneous emphysema and aiding in the resolution of the injury. • Percussion of the chest will establish an abnormal resonance and auscultation will reveal an absence of audible lung sounds over the affected areas. • Thoracic ultrasonography will reveal horizontal air artifacts in the midthoracic or dorsal regions, thereby not allowing the examiner to identify the sliding motion of the visceral pleural against the parietal pleura. Thoracic radiography reveals a horizontal shadow beneath the thoracic transverse processes, which is consistent with a ‘line’ representing the collapsed lung(s). If radiology and/or ultrasonography are not available, then the clinician can use response to suction via a thoracocentesis as a diagnosis. • The treatment of choice is prompt removal of free air via a thoracocentesis and suction. This procedure rapidly re-expands the lung and relieves the respiratory distress. If an open pneumothorax is diagnosed then surgical closure is indicated. Horses of all breeds can suffer from pulmonary bleeding during heavy exercise. • Severely affected horses show moderate or severe post-exercise, bilateral epistaxis. In most such horses the bleeding is bright red and evident within 30 minutes of exercise. In rare extreme cases, horses may die either during or immediately after racing with extreme arterial-like epistaxis and cyanosis. • Some affected horses show poor performance throughout the race, while others may ‘tail-off’ dramatically while others may ‘pull-up’. However, poor performance may be attributable to many other causes. • Milder degrees of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage are commonly detected, endoscopically, in apparently normal racing and other performance horses, without any detectable clinical effect. • Tracheobronchoscopy can be used to estimate the severity of EIPH through a grading system (see Table 3.1). However, the relationship between the amount of blood in the large airways and the actual amount of hemorrhage has not been definitively established. This examination is best carried out 30–90 minutes after exercise. If the first examination is negative but there is a high suspicion then the examination can be repeated 1 hour later. Table 3.1 • Tracheal aspiration and bronchoalveolar lavage: the presence of red blood cells or hemosiderophages in tracheal fluid or BALF provides evidence of EIPH. Red blood cells are present for at least 1 week after strenuous exercise and up to 21 days in the case of hemosiderophages. These procedures are also useful for the detection of concurrent respiratory tract infections. • Thoracic radiography may demonstrate the presence of densities in the caudodorsal lung fields but is not indicative of the severity of EIPH. It is most useful for determining the presence or absence of other disease processes that may contribute to the pathophysiology, such as pulmonary abscesses. • Ultrasonography can also be used with ‘comet tail’ lesions detected in the caudo-dorsal lung fields associated with areas of hemorrhage. • Treatment is aimed at minimizing the effects of recent hemorrhage and eliminating or reducing the severity of subsequent hemorrhage. Difficulties with treatment stem from the fact that the pathogenesis has not been accurately determined and is likely to be multifactorial and different between individual cases. • The current favored preventative treatment for EIPH is administration of furosemide before intense exercise or racing. It is not permitted in all racing jurisdictions. • Other considerations are the use of nasal dilator bands and minimization of factors leading to small airway disease, such as the use of non-allergenic bedding. • The prognosis for horses with clinically significant EIPH is guarded as the condition appears to be progressive with repeated episodes of hemorrhage being common despite treatment and rest. Horses that suffer an episode of EIPH with a concurrent respiratory tract infection appear to have a better prognosis. Many of these cases will not have a repeat episode following treatment of the underlying infection. • The exercise tolerance of affected horses is frequently adversely affected, with a significant number being presented, initially, for investigation of poor or inadequate athletic performance. • Cases generally have an abnormally high resting respiratory rate with a variable degree of nostril flare. • A chronic, harsh, non-productive cough is characteristic. • Without treatment, the severity of the cough often increases over weeks or months, sometimes with episodes of a more acute syndrome superimposed from time to time. • Severely affected horses lose weight dramatically and the increased expiratory effort commonly results in marked hypertrophy of the muscles of the caudo-ventral thorax producing the so-called ‘heave line’. In the severe cases, an obvious, extra, expiratory ‘push’ from the abdominal and thoracic muscles is present, possibly with an associated grunt. • A slight or sometimes more profuse, bilateral, postural, catarrhal nasal discharge is usually present. • Clinical signs and history of a seasonal disorder that can be altered by husbandry practices. • Endoscopic examination of the respiratory tract shows poor mucus clearance from the trachea. • Broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) reveals inflammatory cells in proportion to the severity of the underlying disease and this provides an effective quantitative measure of the severity of the underlying pathology. BAL is preferable to transtracheal washing for diagnosing and differentiating RAO from infectious respiratory disease. • Radiographic examination of the thorax may demonstrate an increase in bronchial and interstitial patterns but this can be difficult to interpret in light of normal changes in bronchial pattern associated with advancing age. Radiography is best used in these cases to differentiate from other, more focal disorders. • Serum allergen testing and intradermal allergy testing have not proven very useful in identifying specific allergens in the horse’s environment. • In horses in which infection is believed or confirmed to be part of the etiology or a complicating secondary factor initial treatment with a course of antibiotics is recommended. • Environmental management is key to control and treatment of many cases. These changes focus primarily on the reduction of dust in the horse’s environment with changes of bedding, soaking of hay or use of hay humidifiers; to all pellet diets in severe cases. • Pharmacological treatment centers on the use of bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Systemic and/or inhaled drugs are used depending on the severity of clinical signs and cost restrictions. There are a variety of protocols for the administration of these drugs largely dependent on the clinical signs of the individual horse. • The condition may be suspected on the basis of an inspiratory noise but endoscopy is required to confirm the diagnosis. (Table 3.2 outlines a grading system for laryngeal anatomy and function.) Table 3.2 Grading system for recurrent laryngeal hemiplegia • The ‘slap test’, which tests the integrity of the thoraco-vagal reflex by observing (or palpating) contralateral laryngeal adduction and abduction in response to a ‘slap’ applied to the thoracic wall, may also be used to demonstrate the malfunctioning of the affected side. The atrophy of the muscle may be suggested by palpation of the muscular process of the arytenoid on the affected side which becomes characteristically prominent. However, a horse may have normal laryngeal function at rest but still have signs of dysfunction when exercised and atrophy of the cricoarytenoideus dorsalis may not be apparent in horses in which the disorder is of recent onset. • Comparative endoscopic examination of the larynx, at rest and at exercise, is particularly useful in establishing the extent of the dysfunction and to determine whether any prior attempts have been made at surgical relief of the obstruction. Due to possible normal function at rest and abnormal function during exercise traditional methods of detection have consisted of listening for inspiratory noises during exercise in addition to scoping at rest but this may in many instances now be replaced by dynamic endoscopy during exercise in horses which are normal at rest. Right-side and bilateral paralyses are sometimes encountered but the etiology of these are usually better defined. • Surgical correction is required if significant airflow obstruction is present. Laryngoplasty, a prosthetic ligature, is currently widely used to stabilize and abduct the affected arytenoid cartilage. Complications following this procedure include: failure to maintain abduction of the arytenoids cartilage, dysphagia and rarely aspiration pneumonia, chronic infection of the prosthesis, ossification of the cartilage, intraluminal polyps, laryngeal edema and chondritis. Horses which have been subjected to this procedure show a stabilized (immobile) arytenoid on endoscopy. • Lateral ventriculectomy (Hobday’s operation), in which the lateral laryngeal ventricles are surgically ablated, has been used for many years to reduce the respiratory noise. It does not however alleviate the increased impedence to airflow during exercise if used alone. Endoscopic examination will readily detect the absence of one or both laryngeal ventricles. • Some cases which prove refractory to treatment by the milder surgical interferences are subjected to sub-total arytenoidectomy and the endoscopic appearance of these is very obvious.

Conditions of the respiratory tract

Congenital/developmental disorders

Wry nose (Fig. 3.1)

Treatment

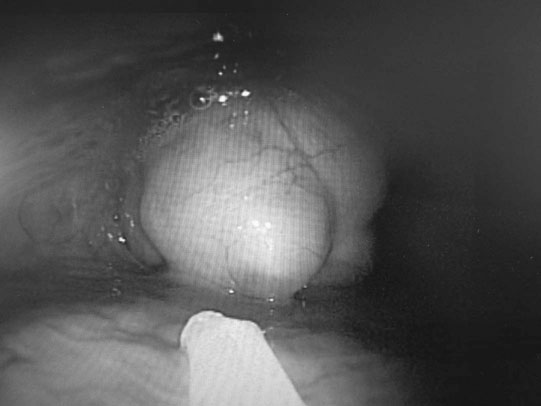

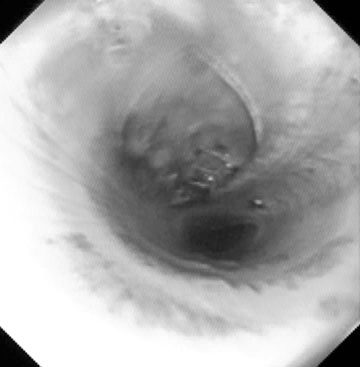

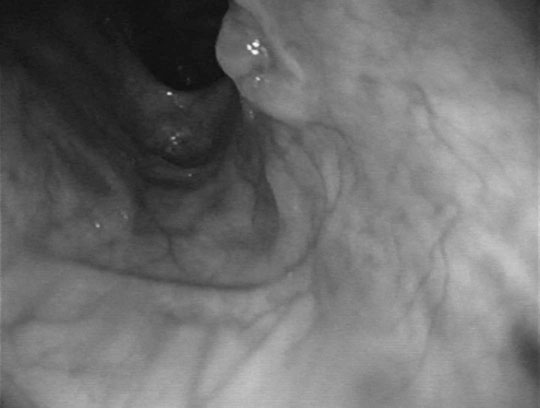

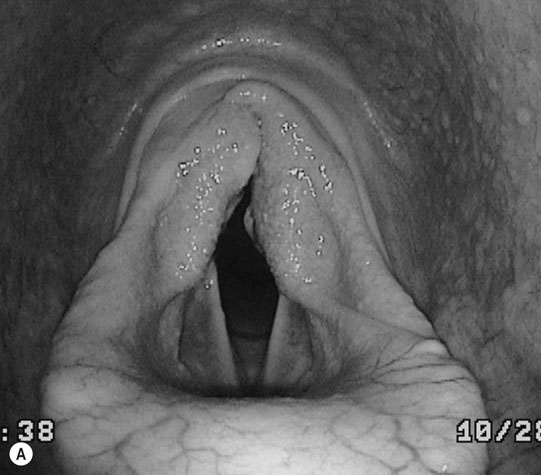

Epiglottic and pharyngeal cysts (Figs. 3.2–3.6)

Differential diagnosis:

Diagnosis and treatment

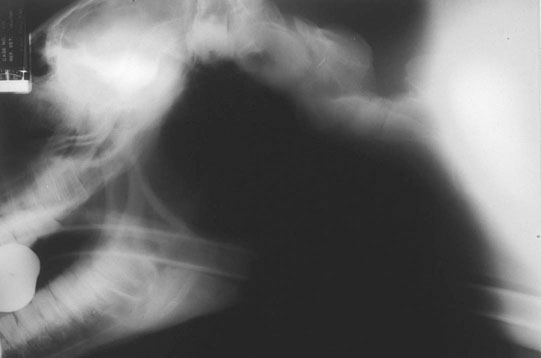

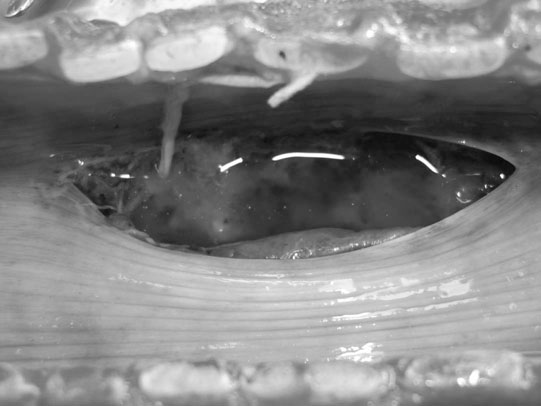

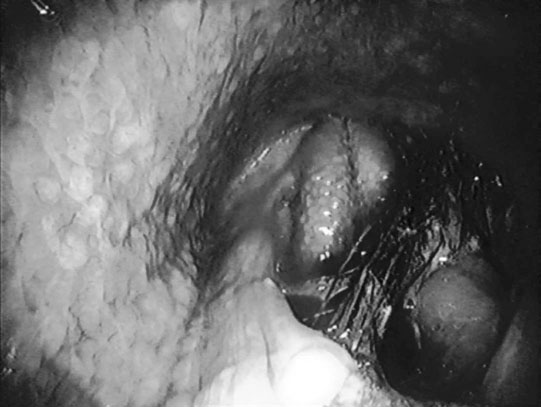

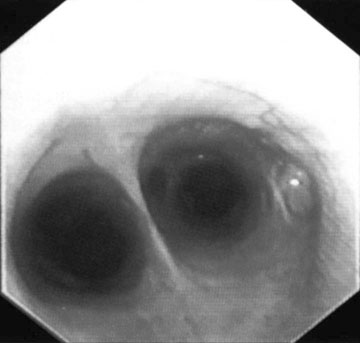

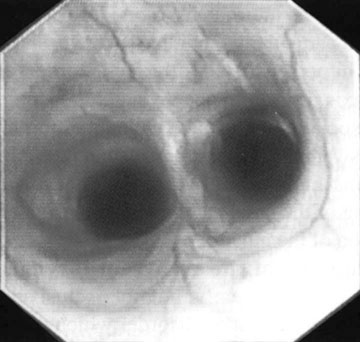

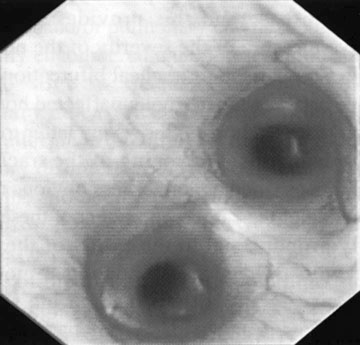

Guttural pouch tympany (Figs. 3.7–3.10)

Differential diagnosis:

Differential diagnosis:

Diagnosis

Treatment

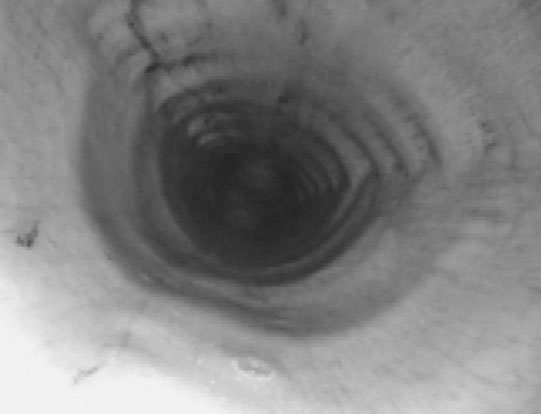

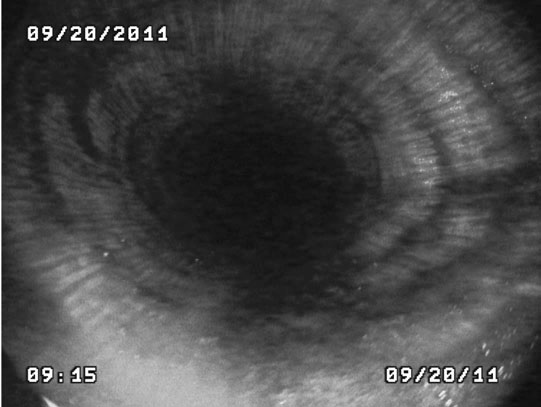

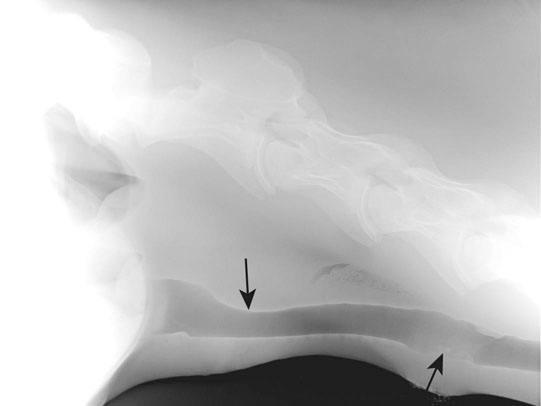

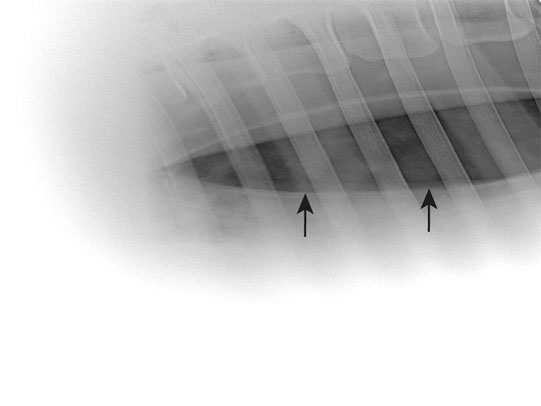

Tracheal collapse (Figs. 3.11 & 3.12)

Diagnosis and treatment

Choanal atresia (Fig. 3.14)

Diagnosis and treatment

Branchial cysts (Fig. 3.15)

Differential diagnosis:

Diagnosis and treatment

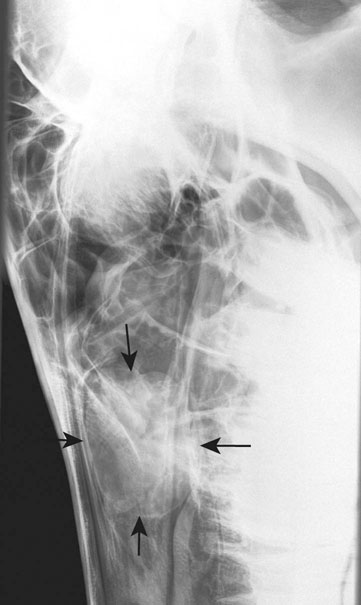

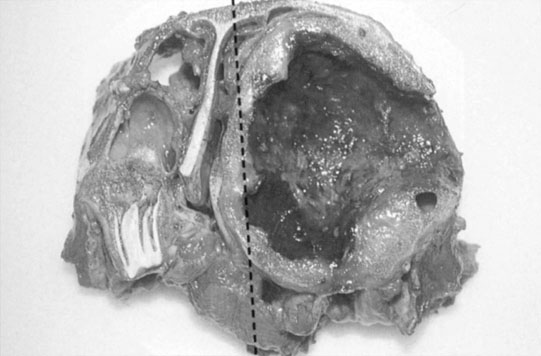

Maxillary sinus cysts (Figs. 3.16–3.19)

Differential diagnosis:

Diagnosis and treatment

Maxillary mucocele

Diagnosis and treatment

Fourth branchial arch defects

Diagnosis and treatment

Non-infectious disorders

Foreign bodies (Figs. 3.21 & 3.22)

Clinical signs

Diagnosis and treatment

Facial trauma (Fig. 3.23)

Differential diagnosis:

Clinical signs

Diagnosis and treatment

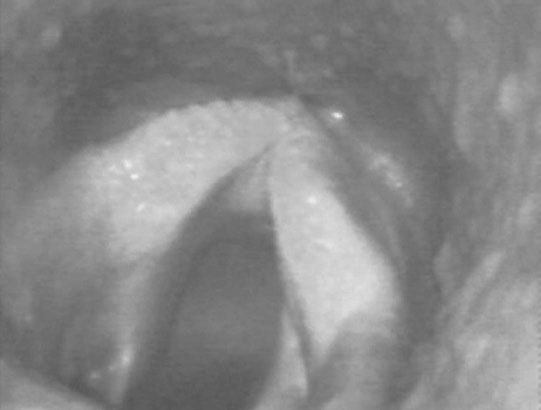

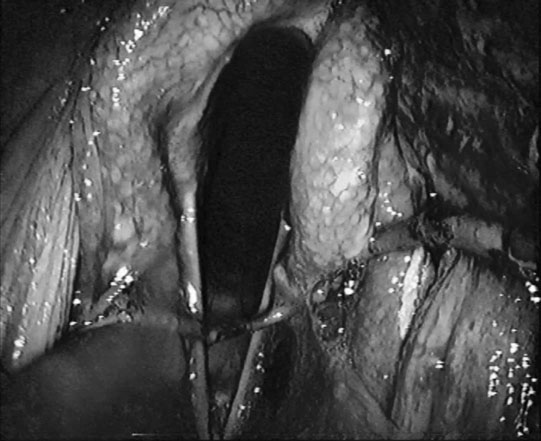

Arytenoid chondritis (Figs. 3.24–3.26)

Differential diagnosis:

Diagnosis and treatment

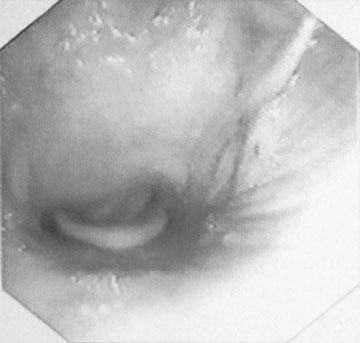

Tracheal perforation (Figs. 3.27–3.29)

Differential diagnosis:

Clinical signs

Diagnosis and treatment

Tracheal chondroma (Figs. 3.30 & 3.31)

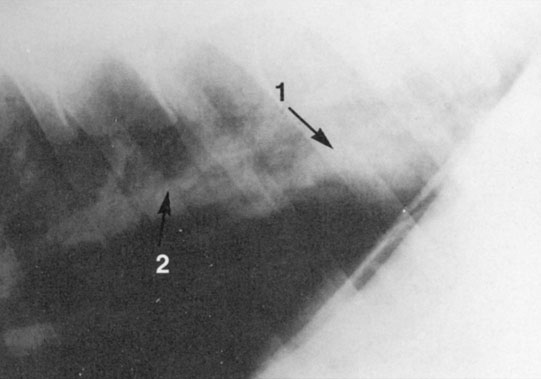

Pneumothorax (Figs. 3.32–3.34)

Diagnosis and treatment

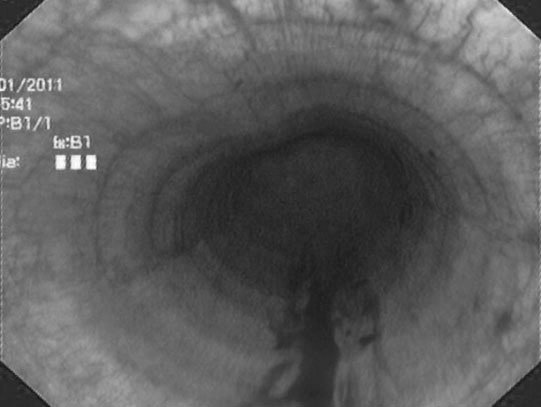

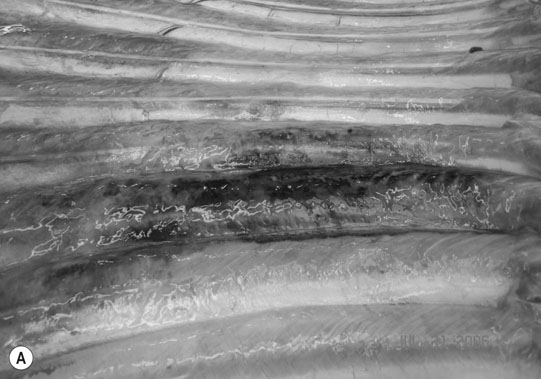

Exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage (EIPH) (Figs. 3.35–3.44)

Clinical signs

Diagnosis

Grade

Tracheoscopic appearance

Grade 0

No blood detected in the upper or lower airway

Grade 1

Presence of one or more flecks of blood or ≤2 short (<1/4 length of trachea) narrow (<10% of the tracheal surface area) streams of blood in the trachea or main stem bronchi visible from the tracheal bifurcation

Grade 2

One long stream of blood (>half length of the trachea) or >2 short streams occupying less than 1/3 of the tracheal circumference

Grade 3

Multiple, distinct streams of blood covering more than 1/3 of the tracheal circumference. No blood pooling at the thoracic inlet

Grade 4

Multiple coalescing streams of blood covering >90% of the tracheal circumference with pooling of blood at the thoracic inlet

Treatment and control

Prognosis

Recurrent airway obstruction and inflammatory airway disease (Figs. 3.45–3.49)

Clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment

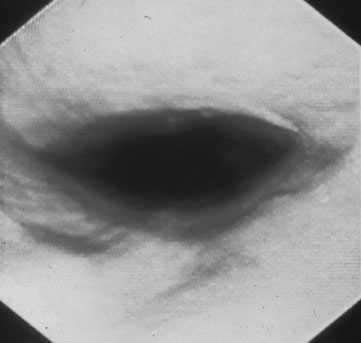

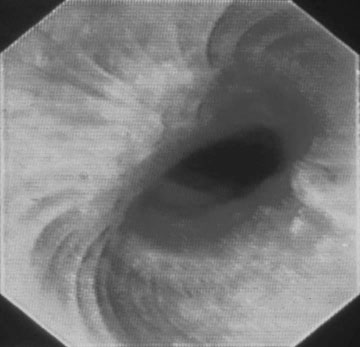

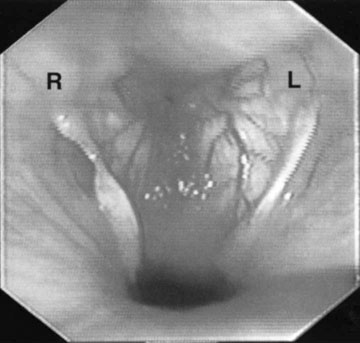

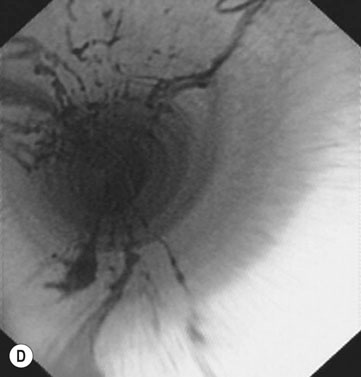

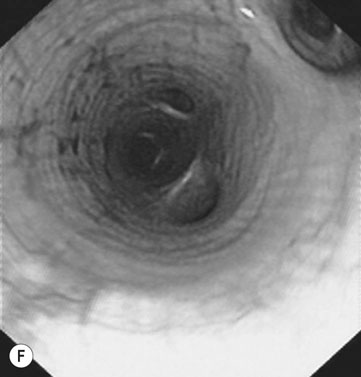

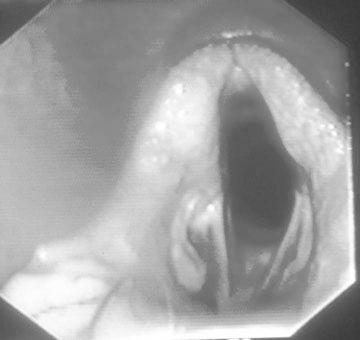

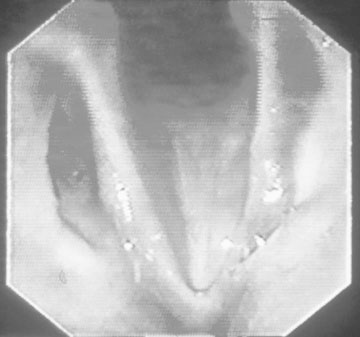

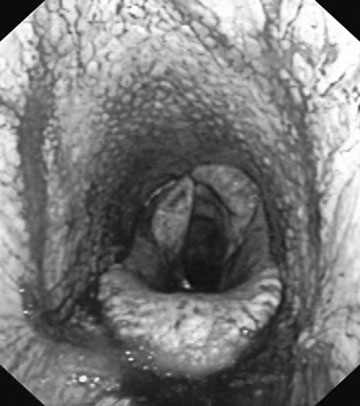

Laryngeal hemiplegia (Figs. 3.50–3.56)

Diagnosis

Grade

Anatomy and function

Grade I

Full abduction and adduction of left and right arytenoids cartilages

Grade II

Asynchronous movement such as hesitation, flutters, adductor weakness of the affected arytenoids during inspiration or expiration or both, but full abduction induced by swallowing or nasal occlusion

Grade III

Asynchronous movement of the affected arytenoids during inspiration or expiration or both. Full abduction not induced or maintained by swallowing or nasal occlusion

Grade IV

Significant asymmetry of the larynx at rest and lack of substantial movement of the affected arytenoids

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree