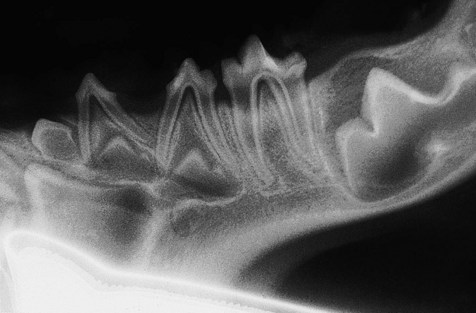

Chapter 8 Periodontal disease is covered in Chapter 9. All dog and cat teeth require a combination of homecare (daily toothbrushing and dental diet/dental hygiene chew) and professional cleaning. Preventive dentistry is indicated for every dog and cat and is detailed in Chapter 10. Odontoclastic resorptive lesions are covered in Chapter 11. Conditions that require prompt management, e.g. traumatic tooth injuries, jaw fracture, and can thus be viewed as ‘emergencies’, are covered in Chapter 12. Extraction is detailed in Chapter 13. Congenital absence of teeth is common in the dog. Radiographs are required to determine whether teeth missing on clinical examination are actually absent or unerupted (Fig. 8.1). This is often of interest for the owner of a dog meant for the show ring. Fig. 8.1 Congenitally missing teeth In humans, anodontia (total absence of teeth) and oligodontia (congenital absence of many but not all teeth) are associated with ectodermal dysplasia (Shafer et al. 1974a). In dogs, anodontia and oligodontia are rare and can be associated with ectodermal dysplasia or occur in dogs with no apparent systemic problem or congenital syndrome (Skrentary 1964; Andrews 1972; Harvey and Emily 1993). Hypodontia (absence of only a few teeth) is, however, a relatively common finding in dogs. It is especially common in purebred and linebred dogs, as the genetic fault will have been perpetuated. It is also more common in small breed dogs. The premolar teeth are the most commonly missing (Harvey and Emily 1993). Supernumerary teeth (Fig. 8.2) are common in certain dog breeds (Harvey and Emily 1993). They are the result of either a genetic defect or a disturbance during tooth development. The duplication of teeth may affect the primary as well as the permanent dentition. Many supernumerary teeth resemble normal teeth, others have a conical shape, and some bear no resemblance to any normal tooth form. The most common complications caused by supernumerary teeth are malpositioning and non-eruption of other teeth (Aitchison 1963; Harvey and Emily 1993). As with other teeth that remain embedded, there is the possibility of cyst formation (Shafer et al. 1974b; Stafne and Gibilisco 1975a; Harvey and Emily 1993). Eruption and shedding disorders are covered later in this chapter. In addition, tooth crowding may contribute to severe plaque accumulation and predispose to periodontal disease. Fig. 8.2 Supernumerary teeth Supernumerary teeth that contribute to malocclusion or crowding should be extracted (Harvey and Emily 1993; Gorrel and Robinson 1995a). Radiographic evaluation allows differentiation between primary and permanent teeth. Primary teeth are smaller than their permanent counterparts, with long, slender roots. Compared with permanent teeth, the roots of primary teeth are relatively long in relation to the crown. The radiographs will also allow you to plan and perform the extractions in a tissue-friendly fashion. Common root abnormalities include aberrations in shape (Fig. 8.3) and in the number of roots present (Figs 8.4, 8.5). They are not detected without radiographs. The identification of an abnormally shaped root or an extra root is not an indication for treatment per se. However, if the tooth is affected by pathology that requires extraction, it is essential to have prior knowledge of an existing anatomic abnormality, so that the extraction can be planned accordingly. Radiographs should always be taken prior to extraction of a tooth. Fig. 8.3 Abnormalities in root shape Fig. 8.4 Abnormalities in the number of roots Fig. 8.5 Abnormalities in the number of roots Enamel hypoplasia (dysplasia) may be defined as an incomplete or defective formation of the organic enamel matrix of teeth. The result is defective (soft, porous) enamel. It can be caused by local, systemic or hereditary factors. Depending on the cause, the condition can affect one or only a few teeth (localized form), or all teeth in the dentition (generalized form). It is essential to remember that enamel hypoplasia results only if the injury occurs during the formative stage of enamel development, i.e. during amelogenesis. Thus, the defect occurs before the tooth erupts into the oral cavity. Crown formation lasts from the 42nd day of gestation through to the 15th day postpartum for the primary teeth and from the 2nd week through to the 3rd month postpartum for the permanent teeth of dogs and cats (Arnall 1960). Depending on the time of the insult, enamel dysplasia will affect primary and/or permanent teeth. As already mentioned, enamel dysplasia may be caused by local, systemic or hereditary factors (Shafer et al. 1974a). Local factors include trauma to the developing crown, e.g. a blow to the face or an infection. Infection is often a consequence of a bite injury. Periapical disease of a primary tooth may cause enamel dysplasia in adjacent developing permanent teeth. Usually only one or a few teeth are affected. Systemic factors include nutritional deficiencies, febrile disorders, hypocalcemia and excessive intake of fluoride during the period of enamel formation. Usually most teeth are affected. Historically, enamel dysplasia in dogs occurred as a result of distemper infection. This is rare today as most dogs are vaccinated against distemper. Hereditary types of enamel dysplasia have been described in humans. The incidence in cats and dogs is unknown. If the enamel dysplasia is the result of a local trauma (Fig. 8.6A) or systemic pyrexia (Fig. 8.7A) that resolves within a period of time, only those areas undergoing active formation during the period of the insult will be affected. This is seen clinically as bands of dysplastic enamel encircling the crown, with areas of normal enamel elsewhere on the tooth. Banding is evident in both Figures 8.6A and 8.7A. Fig. 8.6 Localized enamel dysplasia Fig. 8.7 Generalized enamel dysplasia Poorly protected or exposed dentine is painful. These teeth do become less sensitive with increasing age of the animal since secondary dentine is laid down continuously by the pulp. Another consideration is that dysplastic enamel harbors dental plaque. In severe cases of generalized enamel hypoplasia, where the dentine is effectively exposed to the oral environment, chronic pulp disease and potentially periapical disease may occur as a result of pulpal irritation via the poorly protected or exposed dentine tubules (Fig. 8.7B). Teeth affected by such pathology require treatment, i.e. either extraction or referral to a specialist for endodontic therapy (outlined in the Appendix), if they are to be maintained. The use of professionally applied varnishes and gels associated with a moderate rise in plasma fluoride concentrations may well be safer than daily use of fluoride-containing toothpastes. In other words, it is useful to apply fluoride varnishes or gel at regular intervals. The best time to do this is following a dental cleaning. The product is applied while the animal is under general anesthesia and excess is removed before the animal is allowed to recover. In severely affected cases, the enamel is so soft that it is removed on scaling. In these patients, gross calculus accumulation is carefully removed with hand instruments (a scaler or curette) rather than powered scalers (sonic or ultrasonic). The crowns are polished with a fine grain (to reduce abrasion) prophy paste. Restoration of lost enamel, i.e. debriding the defect and replacing lost tissue with a suitable filling material, is useful for smaller lesions (Fig. 8.6B,C), as it protects against dentine sensitivity. It is not practical for extensive, generalized lesions. Restoration requires referral to a specialist. Unerupted teeth can be detected and evaluated by radiographic examination only (Fig. 8.8). Embedded teeth are those that have failed to erupt and remain completely or partially covered by bone or soft tissue or both. Those that have been obstructed by contact against another erupted or non-erupted tooth in the course of their eruption are referred to as impacted teeth (Shafer et al. 1974a; Stafne and Gibilisco 1975b). Fig. 8.8 Unerupted teeth

Common oral conditions

Introduction

Developmental dental disorders

Anomalies in number, size and shape

Radiographs are required to determine whether teeth missing on clinical examination are actually absent or unerupted. This puppy has a missing permanent 4th premolar.

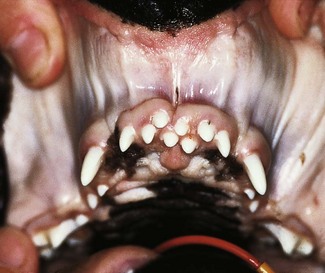

Supernumerary teeth

Supernumerary teeth commonly cause crowding and malocclusion. In this dog, the supernumerary permanent teeth were involved in an incisor malocclusion, resulting in excessive wear of the mandibular incisor teeth and gingival trauma in the upper incisor arch (radiographs were taken to elucidate whether the supernumerary teeth were primary or permanent). Treatment consisted of extraction of the upper incisor teeth that were grossly out of alignment and had abnormal occlusion with the mandibular incisor teeth.

Root abnormalities

The upper 3rd incisor depicted has a marked curvature at its apex. Preoperative radiographs should be taken of all teeth where extraction is planned. Identification of an abnormality in root morphology allows selection of the optimal extraction technique. In this case an open (surgical) extraction technique was chosen.

The upper 1st molar depicted has a small extra root. It was identified on preoperative radiographs. The tooth was extracted owing to severe periodontitis and could thus be removed without sectioning.

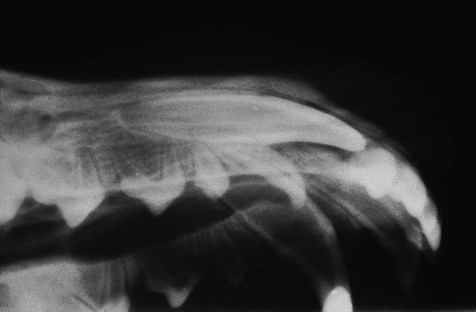

The maxillary 3rd premolar depicted on the radiograph has a palatal root as well as the expected mesial and distal roots. This was an incidental finding on full mouth radiographs. It was bilateral, i.e. both left and right maxillary 3rd premolars had an extra palatal root. If this tooth were to require extraction, it would need to be sectioned into three single-rooted segments rather than the usual two single-rooted segments.

Anomalies in structure

(A) Localized region of defective enamel of the right mandibular canine tooth. This was the only affected tooth in the dentition. This type of enamel dysplasia is likely to be the result of local trauma, e.g. blow to the face. Only the region of enamel undergoing active formation at the time of the trauma is defective, appearing as a band at the gingival third of the crown. The rest of the crown is covered by normal enamel. (B) The defect has been debrided (discolored dysplastic enamel was removed with a round bur in a slow-speed hand piece with water cooling) and prepared to accept a restorative material. (C) Completed restoration using a white filling material (compomer).

(A) Enamel dysplasia affecting all teeth of the dentition. This type of enamel dysplasia is likely to be caused by systemic factors, e.g. pyrexia, at the time of active enamel development. Only the areas actively forming at the time of the insult will be affected as is seen by the obvious banding with areas of normal enamel elsewhere on the tooth. (B) A radiograph of the caudal left mandible of the same dog reveals pulp and periapical disease affecting the mandibular 4th premolar and the 1st and 2nd molars. The full mouth radiographic series showed that almost all teeth of the dentition had evidence of pulp and periapical pathology. The dog was referred to me because her teeth were discolored and the enamel had seemed to ‘crumble’ on ultrasonic scaling. She was 5 years old at the time of referral. Treatment consisted of extraction of all teeth except the incisors and canines as these were unaffected by pulp and periapical disease. Homecare was recommended and annual radiographic examination was instituted. The dog was not amenable to toothbrushing, and further extractions due to pulp and periapical pathology have been performed.

Disorders of eruption and shedding

Unerupted teeth can only be detected and evaluated by radiographic examination. In this patient, the right permanent maxillary canine tooth has not erupted. The right primary maxillary canine tooth is persistent. The owner was not amenable to the regular radiographic evaluation indicated if the unerupted permanent tooth were to be maintained. The chosen treatment in this case therefore consisted of extracting (open/surgical technique) both the persistent primary canine and the unerupted permanent canine.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine