Leporacarus (Listrophorus) gibbus is a non-pathogenic fur mite of rabbits. It is an oval mite with short legs, and so may be distinguished from the above two mites on clinical signs and the absence of a ‘waist’ and having conical suckers and combs on the end of its legs.

Neotrombicula autumnalis is the harvest mite. It is not a true parasite, but the juvenile (six-legged) bright orange-red mite may irritate the skin of rabbits which have access to hay, grass or straw. It causes irritation of the skin surface chiefly over the palmar/plantar aspect of the feet, the face and ears. Its typical orange-red colour is visible to the naked eye, and its six-legged form distinguishes it from other mites.

All of the above mites are surface-dwelling, and may therefore be harvested for identification using a flea comb, or Sellotape® strip applied to the affected area and then stuck to a microscope slide for examination.

Burrowing mites are rare in rabbits, the two main ones being Sarcoptes scabiei and Notoedres spp. They produce intensely pruritic skin lesions, and are diagnosed after skin scrapings and microscopic examination.

Lice

Haemodipsus ventricosis is an uncommon louse in domestic rabbits, and belongs to the sucking (Anoplura) family. It is slender and often blood filled, and may cause significant anaemia in young kits.

Fleas

The rabbit flea is Spillopsyllus cuniculi and is the chief vector for myxomatosis. It tends to concentrate around the ears of the rabbit and may be distinguished from the cat and dog flea by the presence of obliquely arranged genal ctenidium. These are the fronds which line the mouthparts of the flea, and which are horizontal in the cat and dog fleas.

Blow-fly

Blow-flies cause a condition called myiasis (‘fly strike’).

This horrible condition is common in outdoor rabbits that have perineal soiling due to urine scalding or diarrhoea. It is caused by flies including the blue, black and green bottle families. These lay their eggs on the skin of the rabbit. In warm conditions these eggs hatch into larvae within 2 hours. The larvae then mature and burrow into the rabbit.

Other parasites

Coenurus serialis, which is the intermediate host for the adult tapeworm of dogs Taenia serialis, may form large, fluid-filled cysts in subcutaneous sites containing the scolices of the tapeworm.

Viral

Myxomatosis

In rabbits with partial immunity, myxomatosis produces crusting nodules on the skin of the nose, lips, feet and base of the ears (see Figure 5.2). In these rabbits, death can still occur up to 40 days after the initial signs, but many will recover. The acute form of myxomatosis causes oedema of the periocular region, the base of the ears and the anal and genital openings. The virus attacks internal organs as well, and in the unvaccinated domestic rabbit is almost invariably fatal, running a course of 5–15 days.

The myxomatosis virus is a member of the pox virus family, and is transmitted by biting insects, chiefly fleas, but mosquitoes and lice may also provide a source of infection.

Bacterial

Rabbit pus is thick and inspissated. Abscesses are common in the head where they are invariably associated with dental disease. Bacteria involved include Pasteurella multocida and Staphylococcus aureus although, after prolonged antibiotic treatment, many anaerobic bacteria will flourish.

‘Blue fur disease’ is caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which produces a blue pigment, staining the fur, and is common in outdoor rabbits, or those kept in damp conditions. It will infect damaged skin, such as occurs in the dewlap area of many lop breeds, where wet skin chafes.

Rabbit syphilis, due to Treponema paraluiscuniculi, affects the anogenital area, the nose and lips, producing brown crusting lesions. These may progress over the face. This bacterium is thought to be passed from doe to young during parturition, and may be sexually transmitted from buck to doe and vice versa. It is not infectious for humans.

Fungal

The two commonly seen are Microsporum canis, which will fluoresce under ultraviolet Wood’s lamp, and the environmental Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which does will not. The lesions are dry, scaly, often grey plaques appearing over the head initially, but then spreading to the feet and the rest of the body. Culturing brushings of the lesions on dermatophyte medium is advised for definitive diagnosis.

Managemental

The fur of fine- and long-haired breeds, such as the Angoras mats easily, particularly when the animal is bedded on straw, hay or shavings. Owners are advised to keep them on paper or wire mesh, and to groom their rabbit once or twice daily.

Overgrown claws are common, particularly in hutch-kept rabbits with little access to the outside. Claws should be regularly assessed and, if necessary, trimmed on a 4–6-week basis. Overgrown claws can lead to lateral twisting of digit joints and deformity of the foot.

Perineal soiling may be due to faecal soiling from diarrhoea, or inability to consume the caecotrophs which are softer than the faecal pellet. Urine scalding is also common. Older rabbits may have spinal arthritis, which prevents them from positioning correctly to urinate, and lop breeds have excessive folds of skin around the urogenital area. For mild cases, provision of absorbent bedding underneath a deep layer of straw is advised. Attention to cage and rabbit hygiene on a daily basis is essential to prevent blow-fly strike and secondary bacterial skin infections.

Digestive disease

Oral

Dental disease may present from salivation and anorexia, through jaw bone swellings, to full-blown abscesses. Overgrown teeth may be obvious, as with incisor malocclusions, or may be hidden from external view, as with cheek teeth malocclusions. Dental problems may affect other parts of the head, creating abscesses behind the globe of the eye, or the tear duct as it runs over the cheek teeth and maxillary incisor roots, causing pus to appear at the eye or nares.

Causes of dental disease include hereditary defects (Netherland dwarf and lops), due to a shortened rostrocaudal length of skull and abnormal bite (Figure 5.3), or dietary deficiencies. The two most commonly cited dietary deficiencies include a lack of suitable abrasive foodstuffs for dental wear, and a lack of calcium and vitamin D3 for proper jawbone mineralisation.

Rabbits have adapted to survive on a diet consisting of 85% grass, and 15% leafy herbage. Meadow grass is very high in silicates. These are abrasive and are naturally very wearing. Rabbits’ normal dental growth has therefore evolved to cope with this. With a reduced abrasive diet, teeth won’t wear as rapidly and overgrowth will occur. As the rabbit’s mandible is narrower than its maxilla, even wear occurs by lateral movement of the mandible across the maxilla. In less abrasive, easier-chewed diets, this happens less effectively, and so the outer or buccal edges of the mandibular cheek teeth wear, and the inner or lingual edges of the maxillary cheek teeth wear, causing sharp points to form on the tongue side of the mandibular teeth and the cheek side of the maxillary. These points grow, the teeth tilt, and the mandibular teeth then cut into the tongue, and the maxillary teeth into the cheeks leading to deep ulcers, pain and anorexia.

The roots of the cheek teeth may grow back into the jaws as they elongate, due to a lack of space inside the mouth. The roots then push through the ventral aspect of the mandible, and may be felt as a series of lumps underneath the angle of the lower jaw. In the maxilla, the roots of the last two cheek teeth can push into the orbit of the eye, causing ocular pain and epiphora.

Incisors may overgrow due to elongation of the molars pushing the mouth open wider. The maxillary incisors are tightly curved whereas the mandibular incisors are more gently curving. If the mouth is forced slightly open, the maxillary incisors no longer close rostral to the mandibular ones, and overgrowth ensues. The maxillary incisors curl back and into the mouth like ram’s-horns, the mandibular incisors grow up in front of the nose. Maxillary root elongation may also occur when incisors meet end on end, causing constriction of the tear duct which bends around them. This leads to dacryocystitis (inflammation of the tear duct). The duct then dams back and a milky white discharge appears at the eye. This is often misdiagnosed as a primary conjunctivitis (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Ocular disease may be associated with rabbit snuffles but often starts in the tear duct (dacryocystitis) due to pinching of the duct by overgrown (usually incisor) teeth roots.

Other causes of dental disease include physical trauma to the head and inappropriate ‘clipping’ of the teeth with nail clippers. This twists and cracks the tooth root causing further deformity and predisposing to infection.

Radiography of the rabbit head plus close oral examination under sedation or anaesthesia is essential to examine the full extent of the dental problem. Positive contrast techniques may be used in the tear ducts to highlight areas of narrowing or blockage (see Chapter 7).

Gastrointestinal

Dietary

Dietary causes, for example, a sudden change in diet, will lead to temporary diarrhoea. Other dietary factors include the type of food fed. Spoiled foods and part-fermented grass cuttings will inevitably lead to diarrhoea.

Iatrogenic

Iatrogenic causes include the oral administration of certain antibiotics, for example penicillin and clindamycin. These destroy the normal flora of the gut, leaving bacteria such as Clostridium spiriformae or Clostridium perfringens to flourish. These are found in small quantities in the normal gastrointestinal flora of the rabbit, but once they achieve a critical threshold level, they can release toxins which are absorbed into the bloodstream and cause toxaemia and death.

Bacterial

Bacteria, for example Escherichia coli, common in young weaner rabbits, are a cause of sudden death, due to the release of enterotoxins. Death may occur before any signs of diarrhoea. An unknown agent, suspected to be bacterial, is the cause of Epizootic Rabbit Enteropathy (ERE) which is the single biggest cause of mortality in rabbits fattened for the meat industry in Europe. Clinical signs include loss of appetite, over-full stomachs and watery diarrhoea with a high mortality rate. Disease can be stopped by rapid treatment with antibiotics such as tiamulin and bacitracin (Huybens et al., 2008).

Parasitic

Coccidia, for example Eimeria spp., are single-celled protozoal parasites which destroy the lining of the small intestine, causing diarrhoea and death in heavy infestations. In mild cases it may simply cause poor growth and stunting in young rabbits. Eimeria stiedae is of particular importance in rabbits as it will also damage the liver. Coccidial oocysts may be detected in the faeces.

The stomach worm Graphidium strigosum and the small intestinal worm Trichostrongylus retortaeformis are usually only found in rabbits with access to the outside, where they may pick up the eggs of these worms directly from wild rabbits’ faeces or indirectly via passive spread from wild birds, etc. A large intestinal pinworm, Passalurus ambiguus, is commonly seen, but rarely causes disease. All of these worms’ eggs may be detected in the faeces by flotation methods.

Hypomotility disorders

Aetiology and clinical signs

One of the most important factors is the level of indigestible fibre in the diet. A lack of fibre results in reduced motility both by a lack of physical stimulation of the colon due to the absence of large fibre particles and a decreased production of volatile fatty acids in the caecum. Other causes include: increased adrenergic stimulation due to stress or pain resulting in reduced motility (e.g. dental disease, osteoarthritis, etc.); and intestinal infectious diseases, all of which can cause varying effects on gut motility. Most cases in domestic rabbits are due to stress and a long-term dietary deficiency in indigestible fibre.

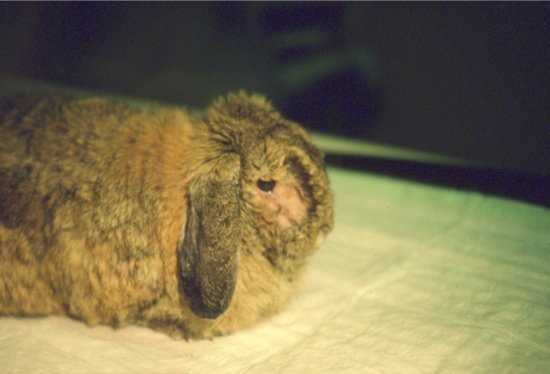

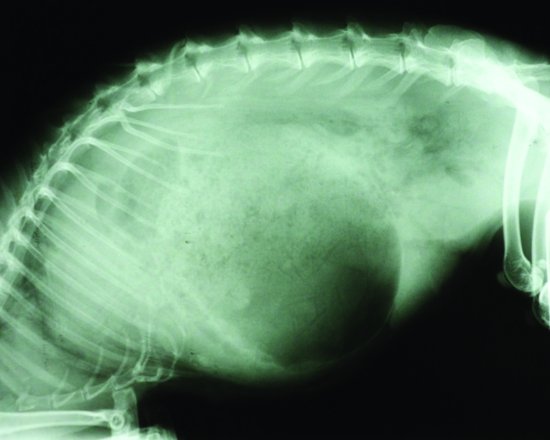

Stomach impaction seen in cases of hypomotility usually comprises a matt of fur and food material. These trichobezoars in rabbits have been blamed for occlusion of the pylorus so causing gastrointestinal motility disorders. The stomach of the rabbit, however, has been shown to always contain food material and groomed fur (Okerman, 1994). Gastric foreign bodies were artificially created using latex, but rabbits affected showed no reduction in appetite or in weight (Leary et al., 1984). It is now widely assumed that trichobezoar formations are due to reduced gastrointestinal motility rather than the cause of it. Intestinal obstructions though can occur and will also lead to stomach distension (see Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 Lateral radiograph of a rabbit with a suspected small intestinal obstruction and a massively dilated stomach.

Onset can be rapid or more insidious. The rabbit is often dull, anorexic and lethargic, may show signs of dehydration and is often suffering from hepatic lipidosis and ketoacidosis. Death, when it occurs, is usually due to liver and kidney failure.

Leporine dysautonomia is another cause of hypomotility. Clinical signs include dry mucus membranes, reduced tear production, dilated pupils, bradycardia, urinary retention (with overflow incontinence), caecal and large intestine impaction, loss of anal tone and proprioceptive deficits. Aspiration pneumonia may also be seen due to megaoesophagus.

Diagnosis

Radiographs of the abdomen may show a distended stomach with food material and an accumulation of gas in stomach and caecum. Blood results show hepatic dysfunction, elevation of hepatic associated leakage enzymes (AST) lipaemia, metabolic acidosis and hyperglycaemia although early cases may show hypoglycaemia, and dehydration as witnessed by an elevated packed cell volume (usually over 45%). Cases where hepatic lipidosis and ketoacidosis are advanced may see damage to the kidneys and resultant elevation in urea, creatinine, phosphate and potassium.

Diagnosis of dysautonomia include absence/reduction of tears on a Schirmer tear test (<3 mm in a minute), dramatic miosis when 0.1% pilocarpine is applied to the eyes, radiography demonstrating aspiration pneumonia, megaoesophagus, impacted/distended caecum and large intestine and distended urinary bladder. Histopathology reveals chromolytic degeneration of the autonomic neurons similar to that seen in equine grass-sickness cases.

Prevention

Ensure all rabbits are fed on a high-fibre diet, for example freshly grazed grass, good quality hay or dried grass. Any stressful procedure where significant catecholamine release is likely to occur, for example post-operatively – it is beneficial to use prokinetic drugs such as metoclopramide and ranitidine and to provide adequate analgesia.

Hepatic lipidosis

Aetiology

Hepatic lipidosis is seen most commonly in overweight indoor rabbits that go through a period of anorexia or food withdrawal.

In rabbits we generally assume that increased mobilisation of fat deposits from a period of anorexia/food deprivation/pregnancy is the main cause. However, stress can increase fat mobilisation in overweight rabbits and minor invasive procedures such as saline injections induced an increase in plasma free fatty acid and glycerol levels in obese rabbits (Lafontan & Agid, 1979). A high-fat diet increases the risks of ketonaemia and so ketoacidosis during anorexia (Jean-Blain & Durix, 1985). Pregnant does between days 24 and 30 are insulin resistant adding to the likelihood they will develop pregnancy ketosis (McLaughlin & Fish, 1994).

The longer the anorexia, the worse the lipid mobilisation and the more the liver is swamped with lipids and free fatty acids. The lipids affect hepatocyte function and make them less able to successfully perform the TCA cycle which is further exacerbated by an absence of glucose in the bloodstream.

Once the liver has become lipidotic, the kidneys frequently follow.

Clinical signs

The early stages may be imperceptible. Most cases are triggered by a period of anorexia, the main clinical signs being reduction in food intake and faecal output. As the condition progresses, the rabbit becomes comatose, hypoglycaemic and acidotic, and dies of liver and kidney failure. Any rabbit anorexic for 12 hours or more (6–8 hours in pregnant does) should be given assisted feeding.

Diagnosis

There is no liver specific leakage enzyme in the rabbit; therefore, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase (CK) are measured together as AST is found in the liver and skeletal muscle, LDH in liver, cardiac and skeletal muscle and CK only in skeletal muscle. GGT elevations are associated with hepatobiliary disease rather than hepatocellular damage, and therefore have been associated with conditions such as hepatic coccidiosis by E. stiedae.

Elevations in triglycerides and cholesterol levels will also occur. There may be hypoglycaemia in severe cases, and levels of β-hydroxybutyrate will be elevated where ketosis is present.

Serum proteins may also be elevated, particularly alpha-2- and beta-2-lipoprotein increases. Finally, ultrasound and endoscopic biopsy of the liver gives a reliable indication of hepatic lipidosis but obviously gives no indication of the degree of ketoacidosis present.

Respiratory disease

Pasteurellosis

Pasteurella multocida causes ‘rabbit snuffles’. It is commonly found in the airways of unaffected rabbits, but it can lead to purulent oculonasal discharge, and wet, matted fur of the forepaws. This can develop into pneumonia. P. multocida contains a dermonecrotic toxin similar to that causing atrophic rhinitis in pigs. Hence many rabbits with these infections are left with permanent upper and lower respiratory tract damage. Poor housing, with damp, ammonia-laden bedding can irritate the airways and allow rapid infection to occur. Dental disease and myxomatosis are other factors. Similarly, overcrowded hutches and concurrent disease elsewhere in the body may lower immunity.

Pasteurella infections may also be found in tooth abscesses and middle ear disease. Infections may result in chronic abscessation of the lungs, mediastinum, pleurae and pericardium.

Other bacterial infections

Bordetella bronchiseptica may be found as a commensal of the upper airways of the rabbit but it can also produce disease. Some strains are cytotoxic and so enhance infections of Pasteurella multocida.

Staphylococcus aureus and S. albus are commonly isolated from the upper respiratory tract of healthy and diseased rabbits. S. aureus can produce toxins which destroy neutrophils as well as protein A which can bind to immunoglobulins. It has been associated with abscessation of the head, lungs, mediastinum and middle ears.

Viral haemorrhagic disease

This is a calicivirus and has been in the United Kingdom since 1992. It does not cause respiratory disease exclusively, as it will attack all organs within the body, particularly the lungs, digestive system and liver. It is spread via contact, and in naïve rabbits it is 100% fatal, often with no obvious clinical disease. Post-mortem examination reveals widespread internal haemorrhage. The disease does not affect rabbits under the age of approximately 10 weeks, as the virus requires the presence of a liver enzyme which is not produced until after this age. Therefore very young kits are protected from the disease.

Cardiovascular disease

Arterial wall calcification

With an excess of calcium/vitamin D3, calcium becomes deposited in the walls of the major blood vessels, reducing their elasticity and leading to increased blood pressure. This is common in the aorta, and may also occur within the kidney parenchyma itself. Some rabbits may be genetically predisposed to this problem. There is no cure. Prevention is aimed at avoiding over-supplementation with calcium and vitamin D3.

Cardiomyopathy and valvular disease

Cardiomyopathy, atherosclerosis and valvular insufficiency with resultant congestive heart failure are also seen in rabbits. The cause of cardiomyopathy is not always clear and rabbits may be asymptomatic. Endocardiosis is seen in older rabbits with the mitral valve being most commonly affected. Alpha-2 drugs such as medetomidine have been associated with myocardial ischaemia and cardiomyopathy development, as has stress. Stress induces catecholamine release resulting in coronary arterial constriction in the rabbit and myocardial ischaemia. End-stage dilated cardiomyopathy may present with congestive heart failure with ascites, dyspnoea and tachypnoea.

Arrhythmias

The most commonly seen arrhythmia in rabbits is bradycardia associated with a heart block. It may also be a cause of syncope and collapsing bunny syndrome.

Lead poisoning

This may lead to anaemia with basophilic stippling of the erythrocytes with Romanowsky stains. Clinically, profound chronic non-regenerative anaemia and neurological signs have been reported. Lead levels above 1.1 µmol/L on heparinised blood are diagnostic.

Urinary tract disease

Urolithiasis and cystitis

Cystitis and urolithiasis are common, as rabbits absorb all of the calcium they can from their diet, and then excrete any excess into the urine via the kidneys. The commonest urolith is calcium carbonate, which forms readily in the rabbit’s alkaline urine, and is radio-dense, often filling the bladder outline on radiographs. Secondary bladder infections are common as the crystals irritate the lining of the bladder. See Table 5.1 for details of urinanalysis.

Table 5.1 Urinanalysis results for healthy domestic rabbits.

| Urine volume | 10–35 mL/kg/day average (depending on diet) |

| Urine specific gravity | 1.003–1.036 |

| Urine erythrocyte numbers | <5 erythrocytes per high power field |

| Urine protein levels | Trace to absent (may be more in juveniles) |

| Urine colour | Varies from pale yellow to deep red depending on presence/absence of porphyrins |

| Urine average pH | 8.2 |

| Urine crystals | Small volumes of ammonium magnesium phosphate or calcium carbonate are normal. |

Haematuria

The presence of red-coloured urine in the rabbit does not necessarily indicate haematuria. Many red porphyrin pigments from the diet (particularly some leafy greens such as beetroot) will be excreted in the urine. Causes of haematuria include cystitis, uterine tumours, aneurysms and kidney infections.

Renal disease

Aetiology

In general, chronic renal failure cases are associated with: E. cuniculi; pyelonephritis; chronic progressive nephrosis; amyloidosis; renal calcinosis; congenital polycystic kidneys (which tend to produce CRF by 2–3 years of age); neoplasia (lymphoma) and renoliths/ureteroliths.

Acute renal failure may be seen associated with: E. cuniculi; pyelonephritis; drug toxicity and renoliths/ureteroliths causing hydronephrosis.

Clinical signs

Chronic renal failure

This is associated with weight loss, dehydration, loss of appetite, polydipsia and polyuria. In addition, a reduction in gastro-intestinal motility, with caecal impaction may be observed. Clinical anaemia may be present and other signs associated with specific conditions (e.g. neurological signs with E. cuniculi infection) may also be demonstrable.

Acute renal failure

The rabbit is usually in good bodily condition, with a history of recent medication administration (e.g. nephrotoxic drugs such as the aminoglycosides, or NSAIDS) or in does in late pregnancy with toxaemia or in obese animals which undergo a period of anorexia where fatty infiltration may occur.

Encephalitozoon cuniculi

This can be a cause of chronic and acute renal failure, and of course, may be associated with neurological signs, for example torticollis, fitting, cataracts and uveitis (often unilateral), muscle tremors, paresis and paralysis of hindlimbs and urinary overflow with urine scalding. Death may occur due to heart failure, renal failure or meningoencephalitis. The organism is a microsporidian parasite found in a wide range of mammals, including rabbits and is a potential zoonotic disease in immunocompromised humans (e.g. AIDS affected individuals). There are different strains of E. cuniculi – strain I (found in rabbits and humans), strain II (found in rodents) and strain III (found in dogs and humans). Infection is by ingestion of food contaminated by infected urine, although vertical transmission is possible in utero. Replication occurs in the kidneys and spreads to the CNS as well as the cardiac muscles. The most common renal presentation is chronic renal disease due to a granulomatous interstitial nephritis and tubular degeneration.

Pyelonephritis/renoliths

Rabbits affected may be in severe pain, sometimes vocalising when passing urine. Urine may be obviously turbid with pus, or blood. Individuals may also have GI associated signs such as increased borborygmi or GI stasis. The patient is often hunched and anorectic. However, some individuals with early renoliths may be clinically unaffected.

Diagnosis

Chronic renal failure

The major acute phase protein in rabbits is C-reactive protein travelling in the beta-globulin fraction. With acute renal failure due to nephritis an increase in alpha-2 globulins is also seen (alpha-2 macroglobulin), as is the case with the nephrotic syndrome. In the nephrotic syndrome (chronic renal disease), there is also an increase in beta-1 globulins (due to transferrin and beta-2 lipoprotein). In chronic renal failure, there is often a significant drop in albumin whereas in acute renal failure there is often elevation (due to dehydration) or normal levels.

In chronic renal failure, urea, creatinine and phosphate levels will be raised, and the patient is often anaemic. Only when <25% of renal functional mass has been destroyed will these blood parameters become elevated, so these are not sensitive. A better assessment of glomerular filtration rate may be made using endogenous clearance rates for creatine. Weisbroth et al. (1974) calculated the normal rate at 2.2–4.2 mL/kg/minute. This requires bladder catheterisation and accurate urine output. Urine protein levels should be minimal or absent, therefore, presence of protein and casts in the urine is significant and may indicate chronic renal failure and/or infection. An assessment of urine protein:creatinine levels can be made using in-house kits for cats (e.g. Idexx), although no definitive normal values exist for rabbits – this author and others use the cut-off range for cats as a reference point.

Ionised and total calcium levels may be elevated and soft tissue mineralisation seen radiographically – most commonly the aorta and kidneys. Hypermineralisation of the bones may also be seen which is not seen in cats and dogs. Hypermineralisation is exacerbated by diets supplemented with vitamin D as rabbits are sensitive to toxicosis.

Ultrasonographically, the renal outline may be smaller than normal (<3 cm craniocaudally and <2 cm ventrodorsally).

Acute renal failure

Blood parameters will be elevated as for chronic renal failure, but there is often renal shutdown and anuria. The main difference between acute and chronic failure is the loss of body condition and generally slower onset of debilitation and polydipsia/polyuria in chronic failure.

Ultrasonographically, the renal outline may be larger than normal (>4 cm craniocaudally and <2.5 cm ventrodorsally).

Pre-renal azotaemia

These can be differentiated from acute renal failure by the presence of other clinical signs, usually cardiovascular/hypovolaemic shock in conjunction with a urine SG of >1.030. Confirmation occurs with reduction of renal parameters with rehydration and treatment of hypovolaemia.

Encephalitozoon cuniculi

Antibodies are produced 2–3 weeks after infection. There is no correlation between antibody levels and degree of spore shedding, or with the severity of lesions at post-mortem. A rising titre over 3–4 weeks is suggestive of recent infection. An IgG and IgM antibody test and a PCR test to detect spores in urine are available.

Hydronephrosis

This may be diagnosed using intravenous pyelography using an iodine-based radiopaque medium (0.5–1 mL/kg) injected through a peripheral vein. Ultrasonography may be used to determine if there is hydropic degeneration. Doppler flow ultrasound may also help to ascertain renal arterial blood flow.

Renoliths/ureteroliths

These may be easily diagnosed via radiography or ultrasonography. Renoliths are usually bilateral. The prognosis is generally guarded as renal damage is common and may be either acute or more commonly chronic. Pyelonephritis may also be present.

Reproductive tract disease

Uterine

Uterine adenocarcinoma

This is a common condition seen in does over the age of four years with reported incidence at nearly 80%. The condition is fatal if not detected early as the tumour readily metastasizes, primarily to the lungs. Radiography of the chest is therefore advised if the condition is suspected, to determine if spread has occurred.

Venereal spirochaetosis

Rabbit syphilis is caused by the bacteria Treponema paraluiscuniculi. The condition is self-limiting, but produces crusting of the anogenital area, the nose and lips.

Pyometra

Pyometras occur in older does, and are often due to E. coli infections of hyperplastic endometrial tissues.

Mammary gland

Mastitis occurs following pregnancy when the kittens are lost or in phantom pregnancy. Many of the coliform type of bacteria involved will release endotoxins into the bloodstream causing rapid toxaemia, fever and death of the doe. Others may just cause severe mastitis with abscess formation.

Mammary gland neoplasia can be seen in older rabbits and is usually benign.

Musculoskeletal disease

Splayleg

Splayleg is an inherited congenital disease wherein the kit cannot position one or more hindlimbs underneath itself. Instead the affected limb sticks out awkwardly. There is no treatment for this condition.

Fractured or dislocated spine

This is common in indoor-reared, poorly fed rabbits. The close confinement leads to weakening of bones and muscles due to disuse atrophy, and the absence of sunlight can exacerbate vitamin D3 and calcium deficiency in a poor diet. Osteoporosis occurs, with spontaneous fractures, often in the lumbosacral area. Compression fractures of vertebral bodies are more commonly seen in the thoracolumbar area.

Other bone fractures

The rabbit skeleton forms a smaller proportion of total body weight than mammals such as dogs, cats or humans. Rabbit long bones also have a thinner, more brittle cortex, and are prone to fissure propagation, shattering with rough handling. Displacement of the superficial flexor tendons in the hindleg may mimic a spinal problem with a shuffling gait and arched back.

In contrast to cats and dogs, in rabbits, distal tibial fractures are the most commonly present fracture, followed by metatarsal fractures and then radius/ulna fractures.

Common causes of hindlimb lameness that may be missed are metatarsal and hindfeet phalangeal fractures.

Osteoarthritis

This is common in large breeds, even in young animals and can affect any joint. Most commonly though the stifles, (due to caudal cruciate damage rather than cranial), hips (often associated with dysplasia) and spine are affected. This may lead to limb disuse, pain, urine staining of the perineum and faecal soiling due to an inability to flex the spine to allow urination and caecotrophy and muscle wasting.

Neurological disease

Encephalitozoonosis

Encephalitozoon cuniculi affects the kidneys and the CNS, and may remain latent for years, producing no clinical signs. Alternatively, paresis/paralysis of the fore- and/or hindlimbs, fitting, head tilt or other vestibular symptoms and blindness may be seen (see Figure 5.6). Diagnosis is as previously described.

Vestibular disease

One cause of vestibular disease is encephalitozoonosis. Others include tumours or infarcts of the hindbrain, and more commonly Pasteurella multocida or other bacterial infection of the middle and inner ear. Bacteria gain access to the middle ear via the Eustachian canal, or less commonly via a perforated ear drum (e.g. in ear mite infestations). Many are unable to stand. Prognosis in advanced cases may be poor. Dorsoventral radiography of the middle ear bullae can demonstrate sclerosis of the bullae and loss of trabecular detail indicating infection. Pus is observed in the external ear canal as the disease originating from the middle ear tends to result in tympanic membrane rupture. For this reason ear drops should not be used in rabbits.

Lead poisoning

Lead poisoning may cause anaemia, and also neurological signs such as fitting, depression and sudden death.

Ophthalmic disease

Uveitis

This is commonly seen in rabbits with Encephalitozoon cuniculi infections where leakage of the lens contents stimulates a phacoclastic uveitis. This is frequently unilateral. Uveitis can also be seen with bacterial infections, for example Pasteurella multocida and, of course, glaucoma.

Glaucoma

New Zealand white rabbits have a recessive bu gene where intraocular pressures may reach 26–48 mmHg. N.B.: most tonometers underestimate intraocular pressure in rabbits. Corneal oedema occurs, but the condition does not appear painful and the eye pressure returns to normal as increased pressure results in damage to the ciliary body which produces the intraocular fluid.

Cataracts

These are commonly associated with E. cuniculi infection, and unilateral. However, congenital and spontaneous idiopathic cataracts have been reported.

Conjunctivitis

The milky discharge seen in rabbit eyes is often mistaken for primary conjunctivitis when dacryocystitis due to dental disease pinching the tear duct occurs. Narrowing of the tear duct can be shown by injecting iodine-based dye into the tear duct through the ventral punctum and radiographing the head (see Figure 5.7). True conjunctivitis may also be seen, and is one of the clinical signs in myxomatosis.

Figure 5.7 An iodine-based positive contrast study of the tear duct of a rabbit with dacryocystitis. Note the syringe with the iodine and catheter to the right and follow the contrast media down to the root of the maxillary incisor where it becomes narrowed.

Aberrant conjunctival overgrowth

This is unique to the rabbit where a fold of conjunctival tissue develops from the limbus of the eye and looks like limbal keratitis. The tissue is not attached to the cornea, but overlies it and may be easily removed. The condition is a congenital abnormality with an unknown aetiology.

Exophthalmos

This is seen due to a cranial mediastinal mass surrounding the anterior vena cava which restricts venous drainage from the eyes. The exophthalmos is not permanent but occurs with stress, often disappearing when the stressful incident goes away. Examples include cranial mediastinal abscesses, lymphoma, thymoma and carcinomas.

Retrobulbar abscesses may result in (usually) unilateral exophthalmos and are associated with cheek tooth abscesses.

DISEASES OF THE RAT AND MOUSE

Skin disease

Ectoparasitic

Mites

Myobia musculi tends to affect the head of mice causing intense pruritus inducing self-mutilation. Some mice may be asymptomatic carriers, but equally some may be so severely affected as to die of secondary bacterial infection (see Figure 5.8).

Myocoptes musculinus causes disease over the body of the mouse. It may produce intense pruritus, but does not tend to induce the large areas of ulceration which are associated with Myobia musculi.

In the rat, the fur mite is Radfordia ensifera. In the tropics, the blood sucking mite Liponyssus bacoti can cause anaemia and general debilitation.

Notoedres muris is a burrowing mite of rats and causes crusting lesions on the ear tips and tail which may then spread to the rest of the body. It is extremely pruritic in the rat and secondary bacterial infections are common.

Diagnosis of these mites is based on the clinical signs and discovering them on skin scrapings.

Lice

The common sucking louse seen in both rats and mice is Polyplax spinulosa. This seems to be mildly pruritic, but if present in sufficient numbers (the louse may be seen with the naked eye), it can cause anaemia.

Fleas

In most pet households, infestation of pet rats and mice with either Ctenocephalides felis or Ctenocephalides canis is possible. These may cause significant anaemia. Xenopsylla cheopis is the main vector for the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the cause of bubonic plague. It is not found in the United Kingdom, but is in parts of Africa, China, South America and the western states of the United States.

Viral

Both species may be affected by their own form of pox virus. These are rare, although the mouse pox virus (ectromelia) can cause problems in laboratories.

Sialodacryoadenitis virus (rat coronavirus) infection is a disease affecting the tear glands and periorbita of rats and mice. It causes local swelling and epiphora. The tears contain porphyrin pigments making them red (chromodacryorrhoea) and mimicking dried blood. The disease is not treatable, but is generally self-limiting, although red tears may reappear in rats at times of stress.

Bacterial

Generalised bacterial skin problems are common as a sequel to any self-induced trauma. Bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. are seen commonly.

Pododermatitis

Sores commonly develop on the hocks of older, overweight rats. They start as pressure sores, allowing secondary infections to occur. Causes include osteoarthritis, excessive weight carriage and poor bedding.

Fungal

In rats and mice dermatophytes such as Trichophyton mentagrophytes produce lesions on the head and neck, with a typical scaling and dry crust. The tail may also be affected, and the lesions do not appear to be pruritic. This ringworm does not fluoresce under Wood’s lamp.

Miscellaneous

Barbering

Barbering of the whiskers and fur is common particularly in male mice kept together. The whiskers and fur is chewed short and may proceed to more serious injuries. For this reason male mice should not be kept together.

Ringtail

Ringtail is seen in rats where circular constrictions of the skin covering the tail occur, stopping the blood supply and causing skin sloughing. It is thought to be due to a reduction in the relative humidity of the environment of the rat. Levels of humidity below 40–50% have been associated with this problem.

Atopy

Atopy is hypothesised to exist in rats. This is an allergic skin condition similar to that seen in dogs, and can occur due to contact with any potential allergen in their environment. Classically, the rat is pruritic and is covered in scabs. There is no evidence of mites on skin scrapings, and no response to ivermectin medication.

Digestive disease

Oral

Dental disease is uncommon in rats and mice. If seen it is usually incisor malocclusion.

Gastrointestinal

Endoparasitic

Pinworms such as Syphacia obvelata (chiefly in mice), Syphacia muris (chiefly in rats) and Aspiculuris tetraptera (chiefly in mice) are common. They may cause no disease at all, but the characteristic asymmetrical eggs may be found in the faeces, or around the anus, where Syphacia spp. may cause irritation. Diarrhoea, if present, is generally mild, but severe infestations may cause rectal prolapses.

Protozoal

These include Entamoeba muris, Trichomonas muris and Giardia muris. All protozoans can cause mild diarrhoea, but many may cause no disease signs at all when present in low numbers.

Bacterial

Salmonellosis:

Mice and rats may remain subclinical carriers of the bacteria for years. Diarrhoea is not always seen, treatment is difficult, as clearing a rat or mouse of Salmonella spp. is almost impossible. Euthanasia may be advised due to the human health risk.

Transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia

Transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia (TMCH) is an infection of mice caused by the environmental bacteria Citrobacter freundii. It causes progressive thickening of the mucosa of the large intestine, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, anorexia and sometimes rectal prolapse, particularly in young mice, 2–4 weeks of age. Death occurs in a small number of cases. The more common outcome is stunting of the mouse. It is highly infectious, and poor cage hygiene allows rapid spread through a colony.

Tyzzer’s disease

This is an infection by Clostridium (Bacillus) piliformis. It is common in rats, where it can cause sudden death, or watery diarrhoea, perineal staining, heart and liver disease. It is highly infectious and spread in the faeces.

Viral

Rotavirus

Rotavirus infection is seen before weaning. Chronic infections, yellow diarrhoea and stunted growth are common.

Mouse hepatitis virus

Mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) is a highly pathogenic coronavirus affecting suckling mice. It causes rapid deterioration, a yellow diarrhoea, muscle tremors, fitting and death in infected individuals, and is spread via the respiratory and faecal–oral routes.

Respiratory disease

Mycoplasma pulmonis

The bacteria Mycoplasma pulmonis is widespread in rats and mice. It is carried in the upper airways and the reproductive tract. Transmission is by close contact between male and female at mating, mother and young during nursing and by aerosol spread from individual to individual over greater distances. It is highly infectious.

Signs of disease include snuffles, head tilts (inner and middle ear infections), dyspnoea, hyperpnoea and death from advanced bronchopulmonary disease. The course of the infection can be chronic, with repeated bouts of bronchitis and pneumonia. They will exhibit poor body condition, a dull staring coat, chromodacryorrhea, anorexia and lethargy. Another presentation includes infertility, reduced fertility and early abortions.

Some factors will encourage onset of the infection and these include other respiratory tract infections,

(e.g. Sendai virus) and unsanitary conditions. Urine soiling which leads to a build-up of ammonia gas which then leads to respiratory tract irritation and infection has also been implicated.

Other bacterial respiratory infections

Streptococcus pneumoniae (a cause of pneumonia and meningitis in humans and therefore a zoonosis), Pasteurella pneumotropica, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Corynebacterium kutscheri and the cilia-associated respiratory bacillus (CAR) may all occur in rats and mice. Clinical signs are respiratory and reproductive disease. Chlamydophila muridarum is the mouse pneumonitis (MoPn) agent, but experimentally mice are also susceptible to C. psittaci and C. trachomatis. In all cases infection is via the respiratory route. Severe acute infections produce ruffled fur, hunched stance, laboured breathing and an interstitial pneumonia. Many will die quickly, but more chronic cases will produce cyanosis of the ear and tail tips.

Sendai virus

This is a paramyxovirus type 1, transmitted by sneezing, direct contact, via food bowls or fomites. It is commonest in recently weaned mice as younger mice are protected by maternal antibodies. Signs of disease include dullness, dyspnoea, chattering of the teeth, weight loss, anorexia and a dull coat. In young mice the mortality rate may be high.

Other viral respiratory diseases

Mouse cytomegalovirus infection

Also known as murid herpesvirus 1 (MuHV-1). Pathology is found in the salivary glands but it can also affect the lungs. Neonates of all mice strains can be affected. Transmission can be via saliva, tears, urine and semen. Clinically apparent disease is rare.

Mouse hepatitis virus

Also known as murine hepatitis virus (MHV) it is a coronavirus. Natural infections are generally subclinical. The virus can infect nasal mucosa, pulmonary vascular endothelium and the draining lymph nodes. It is highly contagious and spread by aerosol and faeces. It is a problem in laboratories. Elimination of the virus may be achieved by stopping breeding of seropositive animals for 8 weeks plus environmental decontamination.

Pneumonia virus of mice

This can infect mice, rats, hamsters, guinea pigs and gerbils. It is a Paramyxoviridae Pneumovirus. In non-immunocompromised rodents it generally produces subclinical infections. In immunodeficient mice it can produce rhinitis, cyanosis, dyspnoea and chronic wasting.

Poxvirus

Cowpox virus can be carried by rodents and may result in disease in other domestic and wild animals (Girling et al., 2011). It is subclinical in rodents. Turkmenian rodent poxvirus has been recorded in laboratory rats in Europe and Russia. Dermal and respiratory lesions with severe respiratory interstitial pneumonia and oedema have been reported.

Diagnosis of viral respiratory disease in rodents

Many laboratories can offer serological testing for rodent viruses. Virus isolation may also be attempted if fresh tissue or lung washes can be submitted.

Fungal respiratory disease

Pneumocystosis

Pneumocystis carinii is an opportunistic pathogen of the respiratory tract of mice, rats and probably all domestic mammals and humans. Transmission occurs by the inhalation of infective cysts. Mice or rats that are immunosuppressed may develop a fatal pneumonia. Affected mice are hunched, tachypneic, with weight loss. Decreased reproductive efficiency is commonly observed in colonies of immunodeficient mice. Histology of the lungs and PCR are used for diagnosis.

Aspergillus spp.

This fungus has been reported as a cause of fatal pneumonia and rhinitis in rats. Corncob bedding was implicated in the source of the fungus.

Other respiratory tract disease

Acidophilic macrophage pneumonia

This can occur in older mice, particularly where there are pulmonary tumours, pneumocystosis or chronic pneumonia. Grossly the lungs appear tan to red in discolouration and do not collapse.

Amyloidosis

This is seen in older mice and hamsters. It can affect any organ and is common in cases of chronic infection and neoplasia. Clinically, the signs depend on the organ affected. It can be more commonly found in male mice, particularly those under stress in overcrowded housing.

Eosinophilic granulomatous pneumonia and asthma

This tends to be a problem in Brown Norwegian rats. It has been associated with asthma, which is common in this breed. However, it has been reported in rats not exposed to allergens, and may be associated with an unknown infectious agent. Incidence can be up to 100% at 3–4 months of age.

Neoplasia

This has regularly been reported in older rats and is often due to primary lung tumours. Metastasis from mammary adenocarcinomas is possible in female mice.

Cardiovascular disease

Atrial thrombosis is common in aged mice, usually in the left atrium; it may be accompanied by amyloidosis. Amyloid is deposited in the walls of the great vessels. Cardiac disease is seen clinically as dyspnoea, tachypnoea and abdominal distension.

Cardiomyopathy and myocardial fibrosis are the two most commonly seen cardiac abnormalities. Cardiomyopathy (usually dilated) is particularly common in male rats that are over-fed, and can be seen as early as 3 months of age. The incidence of myocardial disease can be reduced by 25–30% by dietary restriction.

Endocardiosis and atrial thrombus formation are common in older rats. Myocardial mineralisation may be seen secondary to chronic renal disease. Congestive heart failure will result.

Myocardial abscesses can be seen with Tyzzer’s disease.

Urinary tract disease

Chronic progressive nephrosis

Chronic progressive nephrosis is common in ageing rats and mice. The kidneys become progressively more damaged by protein deposits in the tubular lumens. In certain strains of mice an autoimmune factor is seen. In rats, a high-protein, low-potassium diet has been implicated, with males more susceptible than females. Recurrent disease equally may have a role to play. An increase in thirst and urination may be seen, with weight loss and dehydration. Blood samples demonstrate increased urea and creatinine with low blood albumin.

Urolithiasis

This is common in older rats and mice, especially males, where uroliths may block the narrower urethra proximal to the os penis. The composition varies, but is frequently calcium carbonate, ammonium phosphate or calcium oxalate. There is often a secondary cystitis.

Nephritis/pyelonephritis

Often seen in older rats and involving bacteria such as Pseudomonas spp., E. coli, Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiella spp. Culture and sensitivity testing of cystocentesis collected samples is advisable.

Interstitial nephritis can occur with Leptospira spp. (such as L. ballum) in most rodents and this can be a zoonotic disease. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LMCV) can cause interstitial nephritis and is also zoonotic. Clinically, the rodent presents with anorexia, lethargy, dehydration and abdominal pain.

Renal coccidiosis and bladder worms

Renal coccidian Klossiella hydromyos has been reported in rats, sporocysts being found in the urine. Sulphonamides are effective in most cases.

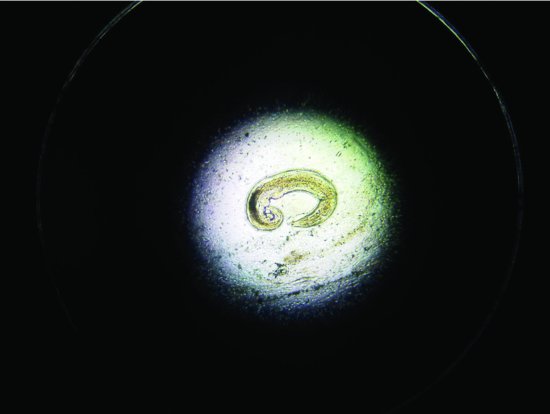

Trichosomoides crassicauda (bladder threadworms) have also been reported in rats (8–12 weeks of age) (see Figure 5.9). Clinical signs include poor growth, staring coats and difficulty urinating/cystitis. Worm eggs may be seen in the urine.

Figure 5.9 An example of the bladder nematode Trichosomoides crassicauda found in the urine of a 12-week-old rat.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree