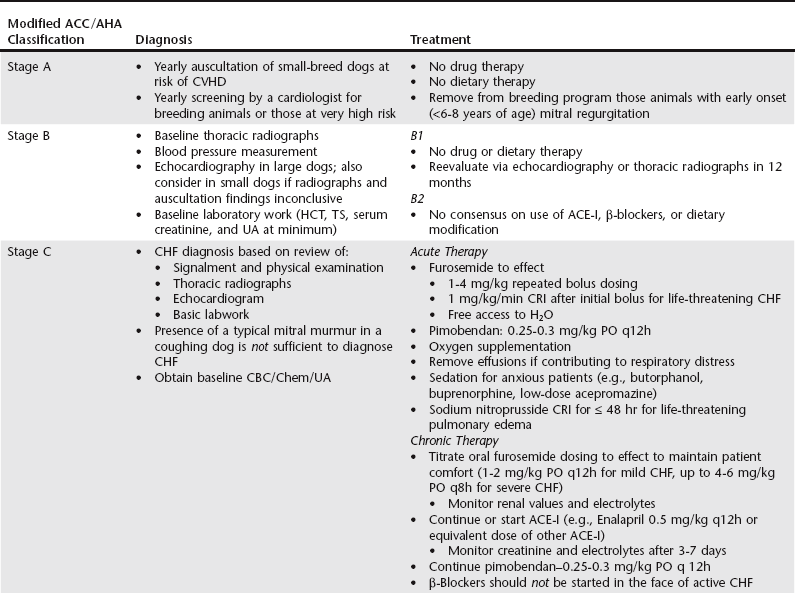

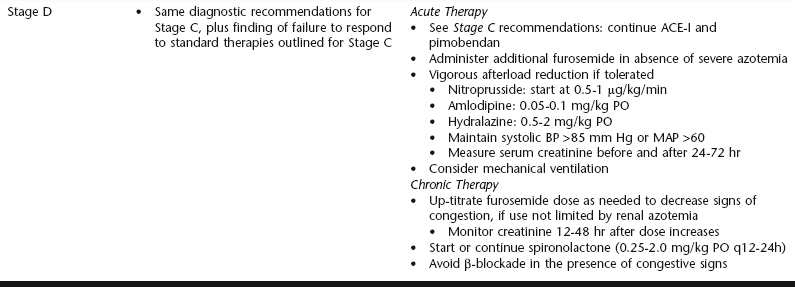

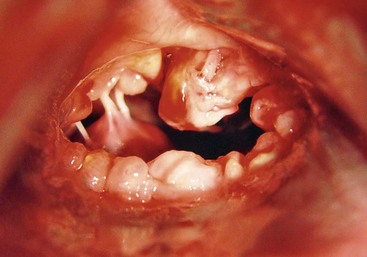

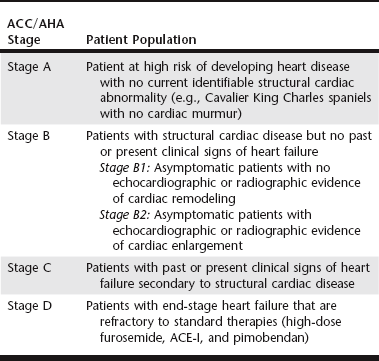

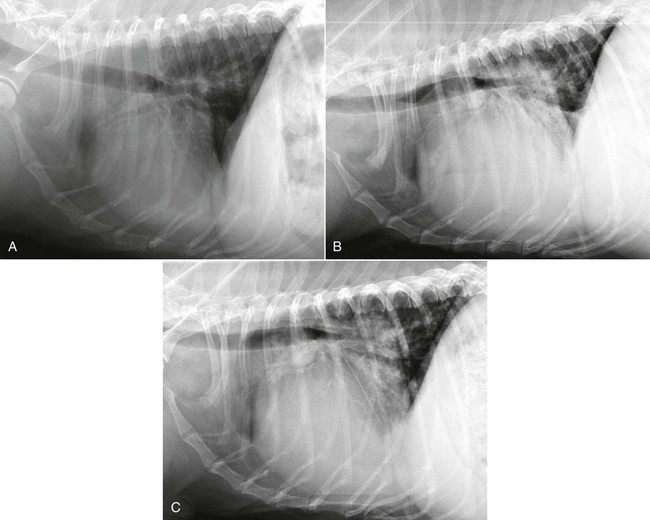

Chapter 177 Advanced myxomatous degeneration leads to grossly thickened and shortened valve leaflets with curled, nodular margins (Figure 177-1). Valvular hemorrhage and calcification may be seen. There is fibrosis of the valves, loss of collagen fibers, and an accumulation of acid-staining glycosaminoglycans within affected valves. Chordae tendineae often are affected and may become thickened, stretched, or ruptured, which allows portions of the diseased valve leaflets to bulge or prolapse into the atrial chamber. Electron microscopy has documented great variation in endothelial cell size and morphology of affected valves, with focal loss of the endothelial layer, collagen exposure, and activation of valvular interstitial cells. It is not clear which of these findings is a result of the disease and which might be a cause or contributor to disease progression. CVHD historically has been considered a noninflammatory, myxomatous degeneration of the atrioventricular valve, but there is growing interest in the role that serotonin or other inflammatory mediators may play in accelerating the pathologic development of the disease. There is one report of elevated C-reactive protein concentrations in the serum of affected dogs, which suggests a possible role of low-grade systemic inflammation in the progression of the disease (Rush et al, 2006). Another study evaluating genomic expression patterns in the valves of dogs with CVHD confirmed activation of several pathways involved in cell signaling, inflammation, and extracellular matrix activation, with several inflammatory cytokines and serotonin–transforming growth factor-β pathways identified as contributory to the development of the degenerative process in the valve (Oyama and Chittur, 2006). Increased serum serotonin levels have been found in dogs with CVHD, and increased autocrine production of serotonin, as well as up-regulation of the serotonin receptor 5HT-R2β, has been detected in affected valves. Increased serotonin signaling or decreased clearance can activate mitogenic pathways in valvular interstitial cells, resulting in their transformation to a more active myofibroblast phenotype. These activated interstitial cells are believed to play a role in pathologic valve remodeling via increased deposition of glycosaminoglycans, collagen turnover, and expression of transforming growth factor-β1 and other signaling molecules (Oyama and Levy, 2010). Further research into the role that serotonin pathways play in the pathogenesis of the valvular remodeling accompanying CVHD is ongoing. Figure 177-1 Gross pathologic image of the mitral valve from a dog with advanced chronic valvular heart disease. The left atrium has been opened allowing visualization of the atrial surface of the valve. Note the severely thickened, shortened leaflets and the retracted, nodular leaflet edges. In addition to valvular abnormalities, many dogs with CVHD have histopathologic lesions in the myocardium, including small foci of myocardial fibrosis and necrosis, as well as more widespread intramural coronary arteriosclerosis (Falk et al, 2006). The role that arteriosclerosis, myocardial fibrosis, and microinfarction resulting from occlusion of these arteriosclerotic lesions might play in the progression toward ventricular dilation, systolic dysfunction, and CHF is not well understood at this time, but these lesions seem to offer possible alternative avenues for investigation as treatment or interventional opportunities. Many dogs with CVHD have an audible murmur for years before the onset of cardiac decompensation and CHF (see Table 177-1 for the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [ACC/AHA] staging classification). An extra systolic sound known as a midsystolic click is often detected before the onset of this murmur and has been associated with mitral or tricuspid valve prolapse; this is a sign of early CVHD. With rare exceptions, clinically significant CVHD is accompanied by a holosystolic murmur of medium to loud intensity. Point of maximal murmur intensity is over the left apex with radiation dorsally and to the right in most cases. In most dogs the intensity of the murmur is correlated roughly with the severity of mitral regurgitation (MR) as long as arterial blood pressure is normal. Thus in dogs with soft murmurs of MR the volume of regurgitation is unlikely to result in clinical signs; however, once a loud murmur is present, one cannot readily predict the onset of CHF in a given dog. TABLE 177-1 Modified ACC/AHA Classification Scheme Modified from Atkins C et al: ACVIM consensus statement: guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of canine chronic valvular heart disease, J Vet Intern Med 23:1142, 2009; and Hunt SA et al: ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 38:2101, 2001. When a murmur is auscultated in a dog without clinical signs, baseline testing can be offered to the owner and often is helpful for comparison at subsequent examinations (see Table 177-2 for American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine [ACVIM] consensus recommendations on diagnostic testing). At a minimum the client should be clearly informed of the presence of the murmur and the fact that the disease ultimately may progress to CHF. Baseline testing ideally should include thoracic radiography to assess for cardiomegaly and optimally echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis and help assess cardiac size and function. A baseline B-type natriuretic peptide or N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level also may be helpful in disease staging, and an NT-proBNP concentration above 1500 pmol/L indicates a higher chance of cardiac decompensation in the next 6 to 12 months. A blood pressure measurement is indicated to exclude systemic hypertension, which might accelerate progression of MR. If hypertension is identified, an underlying cause such as renal or adrenal disease should be sought. Baseline laboratory evaluation should include, at a minimum, assessment of hematocrit, total solids, serum creatinine level, and urinalysis. However, a complete blood count, full serum chemistry analysis, urinalysis, and possible urine protein : creatinine ratio are recommended in hypertensive animals or dogs with other signs of systemic disease. Not only is radiographic evaluation useful for monitoring cardiac chamber size and documenting CHF, but it also serves to guide therapy and exclude other disorders. Pneumonia can develop in an older dog with CVHD and CHF; thus, in a patient with new signs or a poor response to therapy, infection or another problem such as lung cancer should be considered. Chronic bronchitis also is common in many dogs with CVHD and occasionally can be recognized by the presence of severe bronchial patterns or bronchiectasis. The rate of increase in vertebral heart score has been shown to accelerate in the 6 to 12 months before the onset of CHF; thus sequential monitoring of radiographs may be helpful in predicting impending heart failure (Figure 177-2). Figure 177-2 A to C, Serial thoracic radiographs taken from a dog with mitral and tricuspid chronic valvular heart disease. Note the progressive increase in cardiac size, elevation of the trachea, and compression of the left main-stem bronchus. Perihilar infiltrates and a pleural fissure line can be visualized in C.

Chronic Valvular Heart Disease in Dogs

Etiology, Pathology, and Pathophysiology

Evaluation of Asymptomatic Dogs with a Heart Murmur

Evaluation of Dogs with Signs of Cardiac Dysfunction

Thoracic Radiography

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chronic Valvular Heart Disease in Dogs

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue