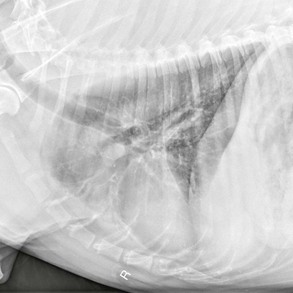

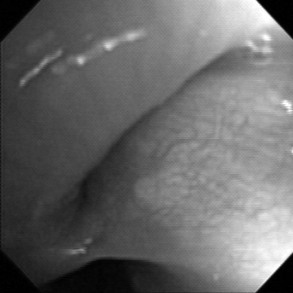

Chapter 160 Clinicopathologic abnormalities typically are absent, even in dogs with infectious bronchitis. Thoracic radiography is an important part of the diagnostic workup, and a generalized increase in interstitial or bronchial infiltrates can be found in dogs with airway inflammation. However, radiography is relatively insensitive for chronic bronchitis, and in a case-controlled evaluation only increased thickness of airway walls and increased numbers of visible airway walls differentiated dogs with bronchitis from normal dogs (Mantis et al, 1998). Dogs with long-standing disease can develop irreversible bronchiectasis, which, when severe, will be visible radiographically (Figure 160-1). Normal-appearing chest radiographs are found relatively often in dogs with chronic bronchitis. Radiographs are also highly insensitive for documentation of airway collapse (Johnson and Pollard, 2010; Macready et al, 2007). Fluoroscopy might be considered the gold standard for identification of tracheal and bronchial collapse, although bronchoscopy is often required to document more subtle degrees of bronchomalacia or small airway collapse. Figure 160-1 Right lateral radiograph for a 9-year-old male castrated chow-chow with a 5-year history of cough. The lobar bronchi to the left cranial lung lobe (both cranial and caudal segments) are obviously dilated with loss of normal tapering, airway walls are thickened, and a distal alveolar infiltrate is noted. Collecting airway samples by tracheal wash or bronchoscopy is recommended to characterize the cellular infiltrate in the airway and to rule out infectious causes of cough. Bronchoscopy is particularly useful when typical radiographic findings of bronchitis are lacking or when bronchomalacia is suspected. Dogs with chronic bronchitis have airway hyperemia, the airway mucosa has a cobblestone or irregular appearance, and many have increased mucus lining the airway. In animals with long-standing bronchitis fibrous nodules can be seen protruding into the bronchial lumen. Bronchomalacia is characterized by a static circumferential narrowing of the bronchial lumen (Figure 160-2) or by dynamic changes in airway caliber during respiration. Figure 160-2 Bronchoscopic image demonstrating bronchomalacia, with 100% collapse of the left cranial lobar bronchus at the top of the image. Cytologically, chronic bronchitis is characterized by the presence of nondegenerate neutrophils. Some dogs have a predominance of eosinophils in airway washings or mixed inflammation, and this might indicate parasitic bronchitis or a form of eosinophilic lung disease (see Chapter 163). Increased mucus is often present, and Curschmann’s spirals (bronchial casts of airway mucus) are sometimes noted. Epithelial cells and squamous metaplasia can also be seen. Dogs with bronchomalacia can have normal findings on cytologic examination of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, can have hypercellular lavage fluid, or can have cytologic evidence of concurrent bronchitis. Whether inflammation is a cause or a consequence of cough has not been determined. Infectious bronchitis is characterized by the presence of septic suppurative inflammation. Organisms are generally recognizable on cytologic examination; however, Mycoplasma spp. are uncommonly seen cytologically and may be isolated only through culture on specialized media or by polymerase chain reaction testing. Caution is warranted when interpreting results of airway specimen culture because the trachea and carina of dogs are not sterile and various species of commensal bacteria and oral flora can be found in tracheal wash or bronchoalveolar lavage samples despite careful attention to technique. True bacterial infections of the lower respiratory tract are characterized by quantitative cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid yielding more than 1.7 × 103 colony-forming units/ml, lack of squamous cells or the oropharyngeal Simonsiella spp. on cytologic examination, and a variably increased percentage of neutrophils (Peeters et al, 2000).

Chronic Bronchial Disorders in Dogs

Diagnosis

Chronic Bronchial Disorders in Dogs

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree