12 Chemical, toxic and physical dermatoses

Chemical trauma

Profile

History of application of ‘pour-on’ or topical medications such as antiseptics, insecticides or fungicides (or other materials) is usually obtained. Application of over-strength medication or of normal-strength medication on an oversensitive skin is a common feature. Application of blisters, counterirritants and vesicants is a common iatrogenic cause of this response, where it is regarded as a good therapeutic effect (see Fig. 12.12). Prolonged skin contact with surgical spirit or other chemicals may arise during general anaesthesia (recumbency) and can cause serious problems which are actually ‘chemical burns’. Historically, old/used engine oil has been used to treat lice and insect bite (Culicoides) hypersensitivity (sweet itch) and this can cause extensive and severe damage to skin and has serious potential systemic toxicity.

1. Common result of inappropriate applications of chemicals to the skin. Mistakes made with calculating concentrations of chemicals or application of misguided ‘cures’. Damage can be severe and is often permanent.

2. Exudative or necrotizing dermatitis following known (or suspected) applications of skin chemicals. Usually lesions are confined to the area of application but systemic effects can be induced. Ingestion by licking of the damaged skin can result in oral ‘burns’ , oesophageal ulceration or necrosis and gastrointestinal damage. Strong chemicals such as arsenicals and oils can cause skin necrosis and severe systemic effects.

3. Diagnosis may be more difficult than it seems because many owners will not readily admit to having caused the damage. Histology is sometimes helpful

4. Treatment depends on removing the chemical as soon as possible using suitable solvents and washes without further skin injury and application of wound management procedures. Systemic effects will require more supportive management.

5. The prognosis is variable depending on the type and extent of the damage and the implications for the anatomical region. Many cases have persistent problems with hyperaesthesia and recurrent infections.

Clinical signs

Acute cases show marked moist, exudative dermatitis with matting of hair (Fig. 12.1). Extensive generalized dermatitis such as is caused by application of engine oil causes severe hair loss and a fragile skin which is easily traumatized. Hair loss (Fig. 12.2) and sometimes even open wounds are common consequences.

Focal application of strong chemicals, focal burns or physical cautery to the skin may result in a dense, coagulated slough (eschar) which may remain in situ for prolonged periods (a ‘sitfast’) (Fig. 12.3) and inevitably leaves a scar.

Differential diagnosis

• Culicoides spp. or other insect hypersensitivity (sweet itch, etc.): seasonally related pruritic condition that depends heavily on exposure to causative insects – usually Culicoides species.

• Louse infestation (Werneckiella (Damalinia) equi, Haematopinus asini): parasites are easily detected by visual inspection and by brushings. Mild pruritus and a moth-eaten appearance may be detected.

• Insect bites with secondary self-inflicted trauma: focal bites following exposure to biting/venomous insects; focus of the bite/sting may be detectable.

• Dermatophytosis (Trichophyton spp.): typical non-pruritic, scaling disorder with characteristic epidemiology and self-resolution within 6–12 weeks; specific therapy resolves the condition and mycological examination is simple.

• Dermatophilosis (Dermatophilus congolensis): distinctive, mildly painful dermatitis localized to wetting areas and exposure to persistent wetting of the coat. Bacteria are easily identified in smears from crusts and pus from the lesions.

• Chorioptic/psoroptic/poultry (red) mite infestation: pruritic disorders mainly restricted to legs and parasites are easily identified. However, they may be present in low numbers so brushings are the ideal specimen to examine.

• Linear keratosis: asymptomatic hair loss in linear patterns often over the neck and lateral chest wall.

• Wounds: obvious crusting at site of wounds unrelated to chemical exposure.

• Scalding: accidental exposure to scalding liquids is very rare in horses.

Diagnostic confirmation

• History of application of pour-on insecticides, blisters or other over-strength medication/applications. Owners, however, may deny having used anything at all. The dermatological evidence may be delayed for days or even weeks after the event.

• The lesions usually have a ‘run-off’ pattern and distribution that corresponds to application of chemicals.

Skin scalding (diarrhoea/urine or wound exudate)

Profile

Wound fluids (whether infected or not) may cause serious excoriation and loss of hair.

1. The skin does not tolerate persistent bathing in body fluids such as lacrimal secretion, blood, serum/plasma, urine or milk. Diarrhoea also causes skin damage, particularly in foals.

2. Signs are associated with bathing in obvious body fluids. Hair matting commonly occurs first. Mild to moderate dermatitis occurs with hair loss and secondary infection.

3. Diagnosis is usually simple. Urine has a characteristic odour and crystallized calcium carbonate is attached to the hair.

4. Treatment is dependent on stopping the contact between the skin and the fluid either by correcting the cause or by protecting the skin in some way. Initially the skin should be cleansed carefully with minimal extra trauma. Dead hair and skin should be removed and the infection controlled appropriately. Thereafter the area should be protected with emollient and soothing water repellent creams or petroleum jelly to allow healing.

5. The prognosis for the skin is good (provided that the primary cause can be managed) but in long-standing cases there may be some persistent changes in hair coat and skin thickness and flexibility.

Tear overflow can also cause superficial dermatitis and this is a primary aspect of facial Habronema infection (see p. 217).

Clinical signs

Diarrhoeic animals (particularly foals) may have mild-to-moderate perineal skin inflammation and temporary loss of hair (Fig. 12.4). The cause of the problem is usually obvious and although it can be significant, controlling the primary cause is the most important aspect of this. Repeated rectal examinations also causes some local irritation and inflammation.

Urine scalding usually occurs around caudal area of hind legs of mares or the lower regions of the hind legs in geldings with urinary incontinence (Fig. 12.5). Where urine is responsible an obvious stale, ammoniacal, urinary smell on legs can be detected. Urine and faeces may contain blood and this can be obvious. Skin may be extensively damaged and exudative.

Hair matting is more obvious with wound fluids; serum exudate appears to induce a moderate or severe dermatitis and this also seems to encourage the development of skin infections. Secondary Habronema musca infestation can occur with wound exudate or lacrimal secretions on the face (see p. 217).

Differential diagnosis

• Dermatophilosis: characteristic distribution and epidemiology affecting horses in poor conditions and subjected to persistent wetting. D. congolensis can be detected in scrapings and smears of exudate and crust.

• Dermatophytosis: localized crusting and scaling dermatosis with characteristic epidemiology and mycology. Most cases spontaneously resolve or respond rapidly to specific treatment.

• Chemical irritants (e.g. strong iodine/disinfectants, mercurial blister): history of application is usually available; characteristic pattern and anatomic distribution corresponding to applications.

• Allergic dermatitis: exudative and no obvious instigatory factors – signs usually restricted to contact regions.

Diagnostic confirmation

• Almost all cases are secondary to other pathology which is usually obvious. A full history and clinical assessment may establish the primary cause.

• If urinary problems are suspected, examine the entire urinary tract to determine whether retention with overflow or cystic calculi is the primary cause.

• History of foaling accident, trauma to hindquarters, e.g. rearing over backwards and landing on sacrum or spontaneous sacral fractures in racing horses.

Treatment

Where treatment of the primary problem is likely to be ineffective, persistent skin care is required, e.g. if there is neurogenic damage or persistent/chronic diarrhoea or wound exudate. The anatomic location of the dermatitis is also an issue. The skin of the distal limb is easily damaged and is liable to infection so this can result in a long-term management problem. Neurological disorders may be permanent and strategies have to be formulated to minimize the secondary consequences. Repeated severe washing with cold water and antiseptic shampoos is not ideal. In some cases repeated washing can in itself be harmful to equine skin. Even surface application of petroleum jelly can eventually be detrimental to skin health.

Actinic dermatoses

Profile

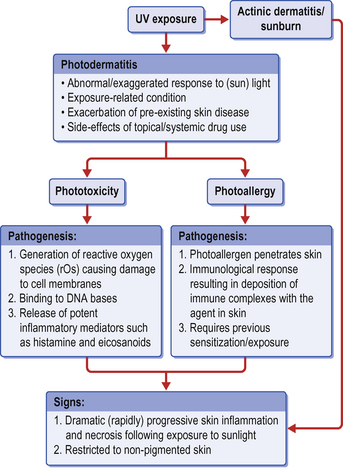

Sunlight (and light derived from other sources) in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum combines short, medium and long wavelengths (UVc, UVb and UVa, respectively). Damage can be caused directly by simple actinic exposure (sunburn) or the various wavelengths of light can react with abnormal (exogenous or endogenous) photosensitizing proteins deposited in the skin (Fig. 12.6). The abnormal response in the latter case is usually much more severe. Melanin protects pigmented skin from the damaging effects of ultraviolet light by absorbing and scattering the ultraviolet light and where skin has little or no melanin the cells can be significantly damaged. All the significant light-related dermatoses are exaggerated in regions lacking in pigment and hair.

Figure 12.6 Light-related skin disorders. Note the aetiopathogenesis of the various types of light-related dermatosis.

Actinic dermatitis may be acute or chronic and falls into two distinct categories:

1. Sunburn (excessive exposure to UV light) with an expected (understandable) outcome. The severity of the damage is dependent upon the strength of the radiation and the sensitivity of the skin to the damage. Pale-skinned horses are far more liable to sunburn than black-skinned horses.

2. Photosensitization (normal exposure to UV light) with unexpected or disproportionate response. In this case even mild exposure causes severe (disproportionate) damage.

Photosensitization requires three factors:

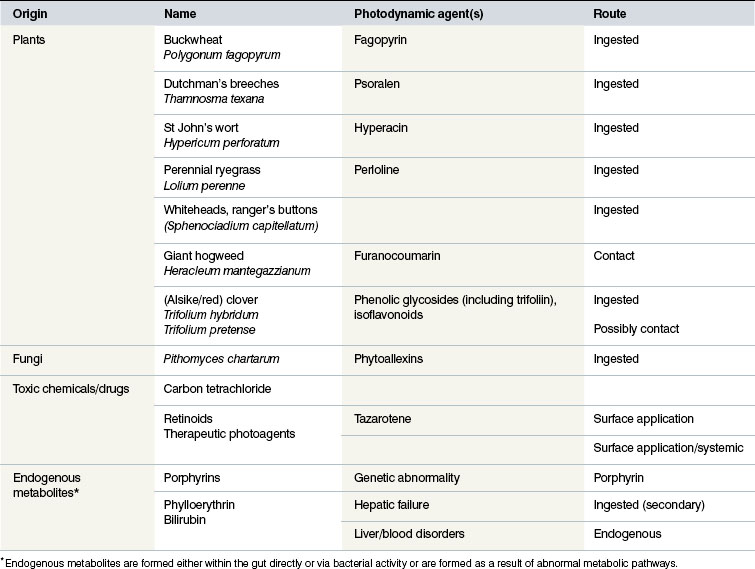

• the presence of a photodynamic agent in the skin (Table 12.1)

• exposure to sunlight or certain wavelengths of ultraviolet light

Photosensitization occurs in three forms:

1. Type 1 (primary) photosensitization. This form is encountered as a result of the ingestion of preformed photodynamic substances such as those found in certain plants (e.g. St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum); Table 12.1) and some chemical ‘poisonings’ (e.g. phenothiazine anthelmintic). The ingested photodynamic agent is absorbed directly from the digestive tract and is delivered to the skin without any hepatic detoxification or alteration. The result is predictable in most horses and is seldom severe.

Primary photosensitization may be involved in some variants of photoactivated pastern and cannon leukocytoclastic vasculitis. In this condition photodynamic complexes may be formed through combination between tissue proteins and plant proteins on the surface of the skin. In these cases the effects can be more severe but remain localized to the exposed regions (see p. 305).

2. Type 2 (endogenous) photosensitization. In these cases endogenously derived metabolites act as photodynamic agents. Examples include porphyrins. This form has not been reported in horses.

3. Type 3 (secondary) photosensitization. Digestion of chlorophyll produces a potent photodynamic agent, phylloerythrin, which is normally detoxified and excreted by the liver. Severe/advanced liver failure allows the substance to pass into the bloodstream unchanged. It accumulates in the skin where it becomes a highly reactive material when exposed to UV light. Severe/extreme actinic damage that is disproportionate to the amount of sunlight applied to the skin is the common presentation. The aetiopathogenesis is related to concurrent hepatic failure and is therefore unpredictable – failure to recognize the primary hepatic disease leads to recurrent episodes and continued suffering.

There are circumstances when the tissue-toxic photoactivity results when a combination of antibody and a photodynamic agent is deposited in dermal and subcutaneous blood vessel walls and the dermis. In this case the response is complicated by autoimmune or other immunological responses that, in horses at least, are poorly understood. An example of this response may be seen in pastern and cannon leukocytoclastic vasculitis (see p. 273).

In addition to the primary and secondary photosensitization conditions that are described below, there are several skin disorders that are exacerbated by exposure to sunshine/UV light. It is suggested that cytokines released by keratinocytes act as the photodynamic agents. Interestingly, sun exposure is usually necessary for the conditions to develop initially; most cases develop in summer months at grass. Once instigated, removal from the sun may have little initial benefit and the condition may persist thereafter without sunlight exposure. Even minor sunlight will trigger exacerbation. These conditions include systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome (see p. 276), and discoid lupus (see p. 270).

Key points: Actinic dermatoses

Key points: Actinic dermatoses

1. Dermatitis of varying severity is caused either directly by the action of ultraviolet light on skin (sunburn) or through the effects of a photodynamic chemical or metabolite deposition in the skin deposited in or on the skin. Endogenous photosensitization as a result of porphyrins etc. has not been reported in horses but some drugs such as phenothiazine can cause the problem.

2. Mild to extreme necrotizing dermal inflammation is characteristic. The proportionality of the damage to the degree of sunlight provides the best indicator of the likely type of photosensitization present. White-skinned areas and pale glabrous (hairless) skin are most liable to the condition.

3. Diagnosis is relatively easy when the dermatitis is restricted to non-pigmented skin in summer months. Histologically the changes are not pathognomonic.

4. Primary sunburn is easily managed by avoidance or sunscreen creams, but the risks associated with repeated exposure should be considered. Type 2 primary photosensitization will resolve if the causative plant/agent is eliminated. For secondary photosensitization as a result of hepatic failure, treatment is usually supportive. Antibiotic treatment and avoidance of sunlight exposure are always sensible. High factor suncreams are not really the answer because they may be used as an excuse to avoid management strategies which are far more effective. Avoidance of any defined causative plant/toxin is essential.

5. The prognosis for primary photosensitization is good. For advanced hepatic failure the prognosis is hopeless.

Ultraviolet light is also potentially mutagenic and carcinogenic but it can also suppress skin inflammation. Therefore sunlight can be both harmful and beneficial. Certain skin tumours, in particular squamous cell carcinoma, are thought to be precipitated by exposure to ultraviolet light and certainly the cutaneous and conjunctival forms of this neoplasm (see p. 427) are much more common in non-pigmented tissues and in regions where more sunlight exposure occurs.

The tissue toxicity effects of light and photodynamic compounds can be used therapeutically in photodynamic therapy (see p. 126).

Clinical signs

1. Simple sunburn (Fig. 12.7) can be difficult to differentiate from the more serious forms of actinic dermatitis but the horse is usually clinically normal and often has very pink skin with minimal hair cover over the muzzle and face. The extent of the damage is usually much less severe than in true photosensitization but repeated exposure can cause significant exacerbation. Most prominent signs are found on the face, commonly around lips, nose and eyelids. If there is significant exudation there may be a complicating superficial infection with Dermatophilus congolensis (see Fig. 6.22). A history of previous problems during summer months is often given. Most (if not all) cases improve quickly when removed from exposure and the skin rapidly returns to normal.

2. The more severe, systemically mediated condition (either from direct photodynamic agents or hepatic failure) is usually much more serious and has a much more destructive nature. Again, the lesions are typically restricted to the white areas on the face and elsewhere (Fig. 12.8) and are always sharply restricted to the non-pigmented skin (Fig. 12.9). Severe cases may have lesions which just overlap into dark-skinned, well-haired areas. Conjunctivitis, skin oedema, erythema, pruritus and pain are usually present as the skin becomes necrotic. The perineum and coronary band region may be severely affected (Fig. 12.8). Extensive sloughing of skin occurs in most severe cases. Concurrent systemic signs of hepatic disease may be present (ventral oedema, hepatoencephalopathy, icterus and weight loss) with biochemical evidence of hepatic failure.

3. Immune-mediated photosensitizations are usually associated with concurrent signs in other body systems. The damage to non-pigmented skin may be more severe than at other sites but usually these conditions have features that make it recognizably different from the damage caused by endogenous or exogenous photodynamic agents. The one unusual form in this group is pastern and cannon leukocytoclastic vasculitis (see p. 273).

Figure 12.7 Sunburn on an unpigmented nose. No other areas were affected and the animal was otherwise very healthy.

The role of plant or toxic chemicals and ultraviolet light in the pastern-related dermatoses (and pastern leukocytoclastic vasculitis in particular) is uncertain but the distribution of the lesions suggests in some cases that sunlight is involved (see Fig. 11.26).

• Generalized lesions are suggestive of liver involvement.

• Localized lesions on lip and distal limb are suggestive of primary photosensitization (pasture plants, sprays or drugs).

• Involvement of the lateral aspects of pigmented digits only may suggest pastern leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

• Involvement of the face only in cream horses or those with lightly pigmented faces may suggest sunburn alone. Sunburnt horses usually have a particular distribution of the skin lesions of the dorsal area of the nose rather than on the upper lip region.

The detection of pyrrolizidine alkaloids on erythrocytes has been described and is probably the definitive test for current ingestion of the plants (Mattocks & Jukes 1991, 1992). Feeds can be closely examined for the plants themselves but this is not always easy and it may be better to analyse the feeds for the alkaloid.

Differential diagnosis

• Sunburn: primary actinic dermatitis arises when there is strong sunlight and is restricted to non-pigmented skin.

• Dermatophilosis (Dermatophilus congolensis): mildly painful, exudative and crusting dermatosis distributed along back and limbs mainly. Organism can be identified in smears from pus and crust.

• Dermatophytosis (Trichophyton spp.): characteristic epidemiology and self-cure within 6–12 weeks.

• Pastern and cannon leukocytoclastic dermatitis: probably a form of photoactivated dermatitis relating to pasture exposure with very restricted anatomic distribution on the lateral pastern/cannon regions.

• Greasy heel syndrome: proliferative verrucose pastern dermatitis condition resulting in massive swelling and nodule formation most often in feathered horses and largely restricted to white limbs.

• Photo-exacerbated skin disorders such as discoid lupus and systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome: rare and much less aggressive skin responses but with systemic signs in some cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Key points: Chemical trauma

Key points: Chemical trauma

. Affected horses usually have varying periods when they are better and worse but may never be normal again.

. Affected horses usually have varying periods when they are better and worse but may never be normal again. Key points: Cheek abscess

Key points: Cheek abscess