Canine brucellosis has high morbidity but low mortality. The clinical systemic signs often are subtle and can include suboptimal athletic performance, lumbar pain, lameness, weight loss, and lethargy.

The primary clinical sign of brucellosis in the bitch is pregnancy loss, which can occur early in gestation (20 days), resulting in fetal resorption, or more commonly (approximately 75% of cases) later in gestation (generally 45 to 59 days), resulting in abortion. Bitches with pregnancy loss early in gestation can appear to be infertile unless early ultrasonographic pregnancy evaluation is performed. Rarely, a litter is carried to term in an infected bitch; neonates die a few days after birth. Nongravid bitches can be infected subclinically or can show regional lymphadenopathy (pharyngeal if orally acquired, inguinal and pelvic if venereally acquired).

The primary acute clinical signs of brucellosis in the male dog reflect disease of the portions of the reproductive tract participating in the maturation, transport, and storage of spermatozoa. Epididymitis is common, with associated orchitis, scrotal dermatitis, and resultant deterioration of semen quality and fertility. Over the long term, testicular atrophy and infertility can occur. The organism can be found in the prostate gland and urine. Antisperm antibodies develop in association with brucellosis-induced epididymal granulomas and further contribute to infertility. Diminished sperm counts (oligospermia), poor sperm motility (asthenospermia), and increased morphologic abnormalities (teratospermia) are characteristic of semen in a Brucella-infected dog. Detached sperm heads, proximal and distal cytoplasmic droplets, and acrosomal deformities are the most common morphologic abnormalities. Sperm head-to-head agglutination suggests the presence of antisperm antibodies. Pyospermia develops 3 to 4 months after infection. An absence of sperm in the ejaculate (azoospermia) also can result.

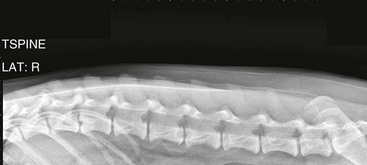

Chronic infections in either sex can result in uveitis, granulomatous splenitis, discospondylitis (Web Figures 83-1, and 83-2), granulomatous dermatitis, meningoencephalitis, and nephritis. Bacteremia can persist for years, and asymptomatic dogs can remain infectious for long intervals.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()