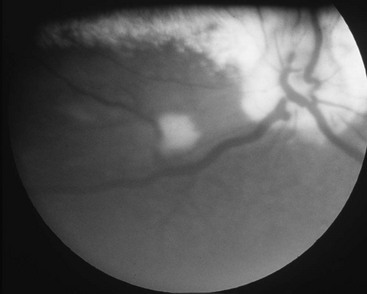

Web Chapter 76 In small animals most RDs are exudative. The subretinal fluid usually is inflammatory but can be serous in diseases such as systemic hypertension (see Chapter 169). The subretinal fluid typically results from breakdown of the blood-ocular barrier in the retinal and choroidal vasculature. Because the choroidal vascular bed is much larger than the retinal vascular supply, a large amount of subretinal fluid usually indicates diffuse choroidal involvement, as seen in diseases such as chorioretinitis, systemic hypertension, or hyperviscosity. Initially areas of chorioretinitis appear as variably sized focal or multifocal areas of retinal elevation with indistinct borders. These active areas of chorioretinitis alter the course of the overlying retinal blood vessels and obscure or blur the ophthalmoscopic view of the underlying retinal pigment epithelium or tapetum as shown in Web Figure 76-1. Web Figure 76-1 Chorioretinitis in a dog caused by blastomycosis. Small areas of active chorioretinitis are associated with focal, low retinal detachments. The term retinochoroiditis is used to imply that retinal tissue was inflamed primarily with choroidal inflammation occurring secondarily, whereas the reverse is true for the term chorioretinitis. Retinitis or chorioretinitis may cause focal or multifocal RDs. As discussed previously, small areas of inflammation are technically RDs, but this type of lesion is best termed chorioretinitis (see Chapters 254 and 255). When choroidal inflammation is severe and diffuse, large segmental or complete RDs may occur. In the dog chorioretinitis with RD may be caused by bacteremia or septicemia (e.g., leptospirosis, brucellosis), rickettsial agents (ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, bartonellosis, anaplasmosis), fungal organisms (aspergillosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and less commonly infection with Acremonium spp. and geotrichosis), algae (protothecosis), and, rarely today, canine distemper virus. Parasitic inflammation of the choroid and retina is more likely to cause smaller areas of detachment (i.e., multifocal chorioretinitis). Causes include ocular larva migrans (due to strongyles, ascarids, Baylisascaris larvae), toxoplasmosis, leishmaniasis, neosporosis, and possibly babesiosis.

Canine Retinal Detachment

Pathogenesis

Causes

Chorioretinitis/Retinochoroiditis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree