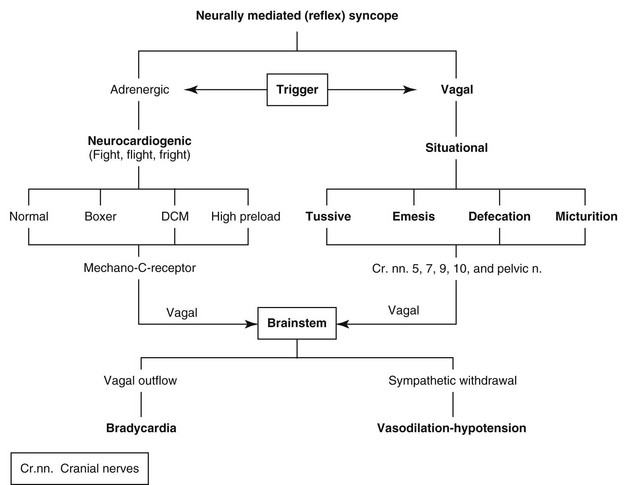

Web Chapter 67 Syncope is a sudden but brief loss of consciousness from which recovery is spontaneous and complete. Presyncope (or near-syncope) refers to a brief, episodic rear limb or generalized weakness, ataxia, or altered level of consciousness. The common denominator is decreased or brief cessation of cerebral blood flow. Heart rhythm disturbances, either rapid or slow, are the most common causes of syncope. Rapid ventricular tachycardia (VT) and reflex bradycardias are most common; the latter also may be associated with reflex-mediated vasodilation. Arrhythmia-induced syncope in small dogs usually is the result of bradycardia (with or without vasodilation); in larger dogs it most often is related to VT. Syncope is less common in cats but can result from either tachycardia or bradycardias such as complete atrioventricular (AV block) (see Chapter 173). One of the most common causes of syncope is rapid VT, especially in boxers with arrhythmic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (see Chapter 179) and Doberman pinschers with dilated cardiomyopathy (see Chapter 178). An inherited VT also occurs in certain families of young German shepherd dogs. Cardiac output and blood pressure can fall precipitously with rapid VT related to shortened diastole, AV dissociation, and aberrant sequence of ventricular activation. All dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy are at increased risk of VT, and sustained rates above 300 beats/min likely will degenerate into ventricular fibrillation and death. Boxers with arrhythmic right ventricular cardiomyopathy without myocardial failure often experience rapid VT and faint. However, as long as left ventricular function is normal, sudden death is unusual, even when VT is sustained. VT in animals with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or subaortic stenosis can cause syncope and death at rates as slow as 180 beats/min. Neurally mediated (reflex) syncope probably is the most common bradycardia-associated syncope (Web Figure 67-1). Neurocardiogenic syncope is triggered by fight, flight, or fright scenarios and can occur in apparently healthy individuals or those predisposed by high preload, genetics (boxer), or dilated cardiomyopathy. The diagnosis often is presumptive.

Syncope

Causes of Syncope

Tachycardias

Ventricular Tachycardia

Bradycardias

Neurally Mediated Syncope

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chapter 67: Syncope

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue