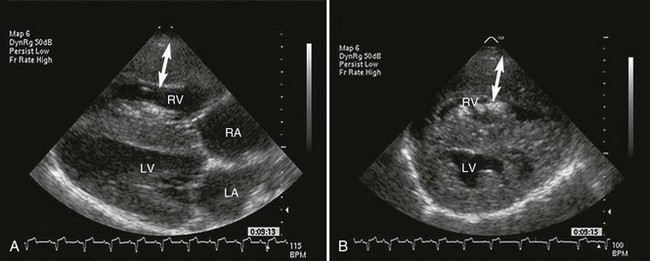

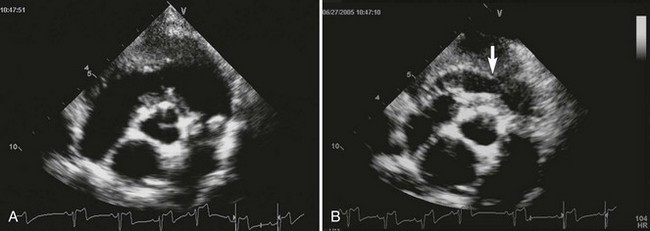

Web Chapter 65 In English bulldogs and boxers PS often is associated with an anomalous origin of the left coronary artery. In these dogs, a single large coronary artery originates from the right aortic sinus (of Valsalva) and then divides into the left and right main branches. The left coronary artery then encircles the RV outflow tract just below the pulmonary valve. This vascular malformation, termed an R2A coronary anomaly, is associated with a subvalvular obstruction (Buchanan, 1990). Two-dimensional echocardiography allows for subjective evaluation of the severity of stenosis. Typical features of PS can be demonstrated clearly from both the right-sided long-axis and short-axis views (Web Figure 65-1). In general, the thicker the RV, the more severe the stenosis. Concentric hypertrophy of the RV, narrowing in the region of the pulmonary valve, and poststenotic dilation of the pulmonary artery are the echocardiographic hallmarks of PS. In severe cases, septal flattening may occur as RV systolic pressure becomes higher than left ventricular systolic pressure (see Web Figure 65-1). Dogs with severe PS also may have hyperechoic regions visible within the RV or septum related to areas of ischemia and fibrosis. Web Figure 65-1 Echocardiographic images from a dog with severe pulmonic stenosis. A, Right-sided four-chamber long-axis view. B, Right-sided short-axis view. Both echocardiographic images show dramatic right ventricular hypertrophy (arrows) and evidence of septal flattening, indicating higher right than left ventricular pressure. Notice also the increased echogenicity of the papillary muscles of the right ventricle, which indicates probable ischemia of this portion of the myocardium. Three features of valvular stenosis that occur to varying degrees are fusion of leaflets, valve thickening, and hypoplasia of the annular region. Valve leaflets may appear prominent because of thickening. Systolic motion of the valve leaflets is restricted, with inward curving at the tips of the leaflets, known as doming, which is most apparent in stenosed but mobile valves. Dysplastic valves often appear very thickened and can be immobile, without the characteristic doming seen with the “typical” valvular stenosis in children. In cases with valve dysplasia or subvalvular stenosis, poststenotic dilation of the pulmonary artery may be absent, and the pulmonary annulus may be hypoplastic. The distinction between the two types of stenosis (typical leaflet fusion and valve dysplasia) often is not clear, and pathologic features of both forms usually are present in dogs. For prognostic reasons dysplastic valves should be assessed for mobility, commissural fusion, and hypoplasia. Annular hypoplasia and immobile valves are likely to respond less favorably to interventional therapy (Bussadori et al, 2001). Evidence of dynamic infundibular narrowing caused by hypertrophy also may be seen on two-dimensional evaluation. During systole, as the walls of the hypertrophied infundibulum come together, obstruction in this region can occur in addition to the valvular obstruction (Web Figure 65-2). The severity of this dynamic stenosis may be difficult to estimate, but it is important to identify it before interventional procedures are undertaken because this type of obstruction can become immediately more severe following balloon valvuloplasty and may require β-adrenergic blockade (see the discussion of suicide RV in the section on treatment later in the chapter). Web Figure 65-2 Echocardiographic images from a dog with severe pulmonic stenosis. Short-axis images obtained at the level of the pulmonary valve. The pulmonary valve is severely thickened and dysplastic. There is no evidence of poststenotic dilation of the pulmonary artery beyond the dysplastic valve. The annulus is normal in size. During diastole (A) the infundibular or subvalvular region is open without evidence of subvalvular obstruction. However, during systole (B) the walls of the hypertrophied infundibulum come together and may create a dynamic subvalvular obstruction (arrow).

Pulmonic Stenosis

Diagnosis

Echocardiographic Findings

Two-Dimensional Echocardiography

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chapter 65: Pulmonic Stenosis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue