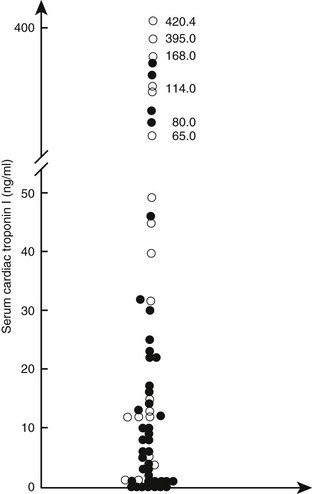

Web Chapter 63 Myocarditis is defined as inflammation of the myocardium in the absence of ischemia that results in injury to the cardiac myocytes and cardiac dysfunction. Because there is no consistently recognizable clinical syndrome or specific noninvasive diagnostic test, the clinical diagnosis of both acute and chronic myocarditis remains problematic and often is only presumptive. There are a variety of causes (Web Table 63-1); infectious agents seem most relevant. Primary myocarditis is presumed to be caused by an acute viral infection or a postviral autoimmune response, neither of which has been well studied in dogs or cats. Secondary myocarditis is inflammation caused by specific pathogens, including bacteria, protozoa, and fungi, and by drugs, chemicals, physical agents, and systemic inflammatory diseases. The causal link between active viral myocarditis and the subsequent development of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is documented in mice and humans but much less appreciated and explored in small animals. This chapter briefly considers some of the current ideas regarding the manifestations, potential importance, and management of canine and feline myocarditis. WEB TABLE 63-1 Causes of Myocarditis in Dogs and Cats Myocarditis has both infectious and noninfectious causes. Cardiotropic viruses, including those with ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) cores, are the predominant pathogens that lead to myocardial inflammation in humans. Current speculation is that up to 30% of human myocarditis is virus associated. However, with the exception of canine parvovirus and to a lesser degree canine distemper virus, the importance of viruses in the development of myocarditis in dogs and cats is largely undetermined. A recent study using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded myocardium from adult dogs with myocardial disease failed to demonstrate an association between prior infection with canine adenovirus type 1 or 2, herpesvirus, or parvovirus and the development of DCM or active myocarditis (Maxson et al, 2001). Slow-growing nonviral agents such as Trypanosoma cruzi also may cause chronic myocarditis with progressive DCM-like pathologic features after a prolonged latent period (Meurs et al, 1995). More recently, Bartonella spp. causing cardiac arrhythmias, endocarditis, and myocarditis in dogs have been identified. Cardiotoxic drugs (e.g., anthracyclines) and drug hypersensitivity reactions have been associated with myocarditis in people. The severity of histopathologic lesions resulting from any of these agents varies with the severity of the insult and the nature and magnitude of the host-toxin interaction. Cardiac injury and myocarditis in critically ill patients often is severe but most commonly remains unrecognized. Potential mechanisms for myocarditis in such patients include excess nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokine production, endotoxins, direct bacterial damage, and ischemia and reperfusion. Traumatic injury of the heart caused by nonpenetrating chest trauma (referred to as traumatic myocarditis) may be associated with myocardial contusion, intramyocardial bleeding, inflammation, and myocardial degeneration and necrosis. Clinically relevant myocardial dysfunction is a rare consequence and almost always is reversible, and arrhythmias usually are benign. There is no evidence of long-term myocardial damage and dysfunction after traumatic myocarditis in dogs and cats (Abbott, 1995). Serum proteomics, including the analysis of circulating biomarkers of myocardial injury such as cardiac troponin (cTn) concentration, is a promising approach to diagnose acute myocardial injury. Certainly the findings of ventricular arrhythmia with a significantly elevated cTn level should prompt consideration of myocarditis in the differential diagnosis. Unfortunately, blood cTn level is not altered consistently in myocarditis, nor is cTn elevation specific for myocardial inflammation. In addition, the time window for diagnosis may be relatively brief. Nevertheless, elevation of serum cTn concentration in association with a strong clinical suspicion may aid in the early presumptive diagnosis of acute myocarditis, in which significant myocytolysis and myocardial necrosis may occur (Web Figure 63-1). Experimental studies in mice and clinical studies in humans with histologically proven myocarditis reported a high sensitivity of cTn level in the diagnosis of fulminant or acute myocarditis and a close relationship between serum concentrations of cTn and the severity of myocardial inflammation. The value of cTn in the diagnosis of chronic myocarditis is limited. Serologic testing for known infectious causes (including toxoplasmosis, borreliosis, rickettsial diseases, bartonellosis, and Chagas’ disease) may identify the causative antigen and assist in development of further treatment plans. The identification of novel biomarkers of cardiac inflammation in peripheral blood, including analysis of messenger RNA and specific proteins (e.g., antimyocardial antibodies such as antimyosin and antitroponin) is under way. Web Figure 63-1 Serum cardiac troponin I (cTnI) concentrations in 60 dogs with the clinical diagnosis of acute myocarditis. Diagnostic criteria were the sudden onset of unexplained ventricular or supraventricular ectopy in dogs that do not commonly develop DCM, abnormal diffuse or focal thickening of the left ventricle with granular texture of the myocardium on two-dimensional echocardiography, left ventricular systolic dysfunction with no or only minor chamber dilation, or vegetative endocarditis associated with ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Dogs with known structural heart disease (congenital and acquired), recent trauma, a splenic mass, neurologic disease, and gastric dilation-volvulus syndrome were excluded. Open circles represent dogs with acute myocarditis confirmed by histopathologic analysis. Zero cTnI refers to the lower limit of detection of the immunoassay used (0.1 ng/ml; OPUS Troponin I assay). (From Schober KE: Unpublished data from the veterinary medical database of the Department of Small Animal Medicine, University of Leipzig, Germany.)

Myocarditis

Infectious

Viruses (parvovirus,* paramyxovirus,* herpesvirus, coronavirus, adenovirus, others)

Bacteria* (various)

Rickettsiae (Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, Coxiella, Bartonella*)

Spirochetes (Borrelia,* Leptospira*)

Fungi (various)

Algaelike organisms (Prototheca)

Protozoa (Trypanosoma,* Toxoplasma,* Neospora, Hepatozoon)

Parasites (Toxocara, Trichinella, Echinococcus)

Physical

Traumatic chest or body impact

Hyperthermia

Immune mediated

Prior infection

Systemic disorders

Drug hypersensitivity

Toxic

Drugs and vaccines

Toxins (anthracyclines, others)

Other

Idiopathic

Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree