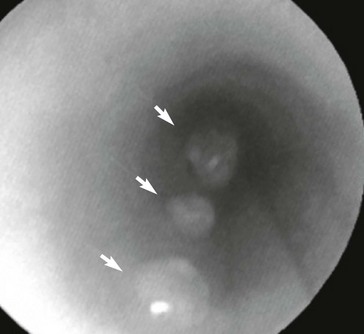

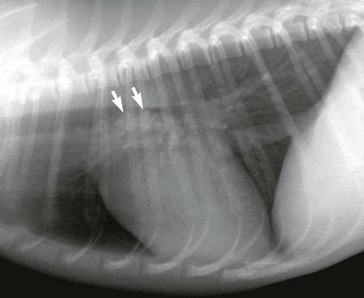

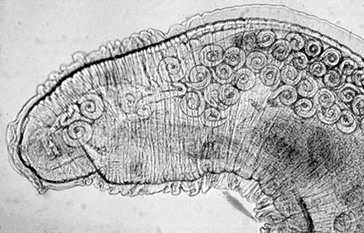

Web Chapter 57 Various parasites, including nematodes, trematodes, protozoa, and arthropods, have a predilection for invading the nasal cavity, airways, lung parenchyma, and pulmonary arteries of dogs and cats. This chapter focuses on primary parasites of the respiratory system that live in the nasal cavity, airways, or lung tissue. Intestinal parasites that transiently migrate through the lung during development such as Toxocara canis and Ancylostoma caninum are not discussed here. Systemic parasitic infections that occasionally cause pulmonary disease such as infection with the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii also are not included. In addition, cardiovascular parasites that live primarily in the heart or pulmonary arteries (Dirofilaria immitis, Angiostrongylus vasorum) are beyond the scope of this chapter, although these are important causes of secondary cardiopulmonary disease (see Chapters 183 and 184). Eucoleus infection may be clinically inapparent or it may cause signs of chronic rhinitis, including sneezing, mucopurulent or blood-tinged nasal discharge, nasal congestion, and reverse sneezing. Aberrant migration through the cribriform plate caused intracranial infection and seizures in one dog (Clark et al, 2013). The diagnosis is confirmed by the microscopic identification of characteristic clear to golden barrel-shaped eggs with clear bipolar plugs on routine fecal flotation or in nasal flushes. Egg excretion may be cyclical and easily overlooked, so multiple fecal examinations may be needed to detect infection. E. boehmi eggs are misidentified easily as eggs of Eucoleus aerophilus (see section on E. aerophilus later in the chapter) because of their similarity in appearance; however, E. boehmi eggs are slightly smaller (50 to 60 µm × 30 to 35 µm) and have a distinctive finely pitted shell surface with readily visible spaces between the eggshells and embryonated contents. Eggs of E. boehmi also resemble those of the whipworm Trichuris vulpis, but whipworm eggs are larger and have a smooth outer shell. Adult E. boehmi nematodes attached to the nasal mucosa occasionally are identified during rhinoscopy and in nasal mucosal biopsy specimens. Effective treatments for E. boehmi include an extended course of fenbendazole (Panacur; 50 mg/kg q24h PO for 14 days), milbemycin oxime (Interceptor; 2 mg/kg PO repeated at 1- to 2-week intervals for a total of three doses), or ivermectin (Ivomec; 0.2 to 0.4 mg/kg SC or PO repeated at 2-week intervals for a total of two or three doses). Ivermectin should not be administered to collies, shelties, and other herding breeds without first determining safety by performing an MDR1 (multidrug resistance 1) genotype test (available at www.vetmed.wsu.edu/vcpl). A single topical spot-on application of moxidectin (2.5 mg/kg) in a formulation with imidacloprid (Advantage Multi) was effective in a dog. During and after treatment, feces should be removed from the dog’s environment to prevent reinfection through coprophagia. Successful treatment is confirmed by clinical response and follow-up fecal examinations. Relapses can occur after initial treatment, necessitating additional courses of therapy. Nasal mites can be treated effectively with selamectin (Revolution; 6 to 12 mg/kg applied topically as a spot-on treatment to the skin over the shoulders at 2-week intervals for a total of three doses) or milbemycin oxime (0.5 to 1 mg/kg PO at 1- to 2-week intervals for a total of three doses). Ivermectin (0.2 to 0.4 mg/kg SC or PO; see precautions in the section on E. boehmi) is an effective alternative, but it has a greater risk of adverse effects. Clinical signs usually resolve rapidly with treatment. In dogs confined together effective control requires treating all animals in the household or kennel facility. Cuterebra spp. larvae are the larval maggot forms (bots) of numerous species of arthropod flies that infect mostly rabbits and rodents. Cuterebra occasionally can infect outdoor dogs and cats in spring and summer and migrate especially in the subcutis of the face, head, and neck region. Rarely Cuterebra larvae can cause respiratory disease when they migrate in the nasopharynx, causing sneezing and unilateral bloody nasal discharge, or in the wall of the cervical trachea, causing clinical signs of cough and airway obstruction. The diagnosis is made by direct endoscopic visualization of the Cuterebra larvae embedded in the nasopharyngeal or upper airway mucosa. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Cuterebra-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies looks promising as a serologic test for presumptive diagnosis of invasive cuterebriasis (Davis et al, 2013). Airway Cuterebra can be treated by endoscopic extraction or by administration of a single dose of ivermectin (0.2 to 0.4 mg/kg SC; see precautions in the section on E. boehmi). Before endoscopic extraction is performed, injection of an antihistamine and corticosteroid is advisable to prevent anaphylaxis if the Cuterebra ruptures. The use of prednisone (1 mg/kg q12h PO for 2 weeks) may reduce the local inflammatory reaction to the parasite. Linguatula serrata, a pentastomid parasite, is a large crustacean-like arthropod that firmly attaches to the mucosa of the nasal passages of dogs, causing signs of chronic rhinitis (sneezing, nasal discharge) and nasal obstruction. Infected dogs have been reported in parts of Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, South America, and Australia. Adult females grow up to 10 cm long and males are 2 cm long. The wormlike body is tan and annulated. After a prepatent period of 6 months, eggs are shed in the nasal secretions of dogs and are ingested by an intermediate host, especially ruminants such as sheep. The larvae hatch and develop as nymphs in the viscera of the intermediate host. The life cycle is completed when a dog ingests sheep offal and the parasite migrates from the dog’s pharynx into its nasal passages. L. serrata is diagnosed by visualization of the adult parasite in the nasal passages or by identification of yellow oval eggs (80 µm in length), which contain four-legged larvae, in nasal secretions. Treatment usually is by physical removal of the parasite, but ivermectin (0.2 to 0.4 mg/kg SC; see precautions in the section on E. boehmi) may also be effective. Bronchoscopy is the most reliable way to detect the distinctive tracheobronchial nodular lesions (granulomas) caused by O. osleri (Web Figure 57-1). In some dogs these nodules also can be identified on thoracic radiographs or computed tomographic scans as large, space-occupying mucosal masses protruding into the lumen near the bifurcation (Web Figure 57-2). The diagnosis of O. osleri infection is confirmed by identification of thin-walled larvated eggs (80 by 50 µm) and coiled larvae (230 to 267 µm with kinked tail) in airway washings or bronchoscopic biopsy specimens. Biopsy samples of parasitic nodules often reveal numerous O. osleri larvae, eggs, and adult worms embedded in granulomatous inflammatory tissue (Web Figure 57-3). Web Figure 57-1 Tracheoscopic image of the distal trachea of a dog with Oslerus osleri infection. Three mucosal masses are evident. Mature parasites can be found within or adjacent to these nodules. Web Figure 57-2 Lateral radiograph of another dog with Oslerus osleri infection. Notice that the mucosal nodules and inflammatory reaction have reduced the tracheal luminal diameter (arrows). Web Figure 57-3 Biopsy sample from a mucosal nodule demonstrating a portion of a female Oslerus osleri parasite carrying numerous larvae.

Respiratory Parasites

Nasal Parasites

Eucoleus boehmi

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

Treatment

Pneumonyssoides caninum

Treatment

Cuterebra

Linguatula serrata

Bronchopulmonary Parasites

Oslerus osleri

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chapter 57: Respiratory Parasites

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue