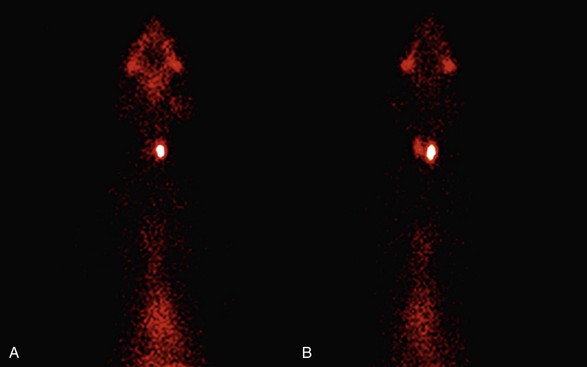

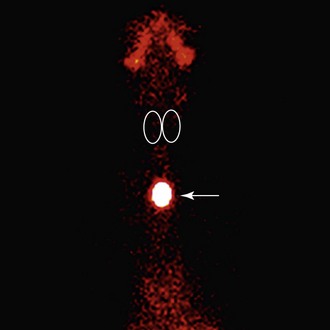

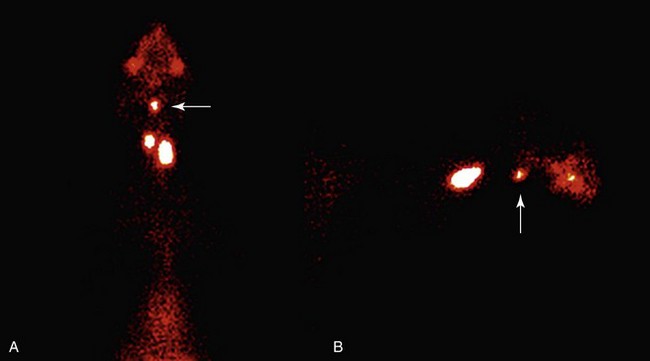

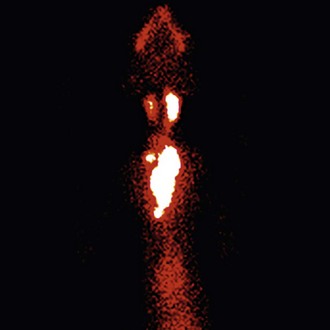

Web Chapter 21 1. Routine database, including a complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry panel, and complete urinalysis 2. Pretreatment or untreated serum total T4 concentration (with the cat not on antithyroid drug treatment or a low-iodine diet); if the cat has been treated medically for longer than 1 to 2 months, the antithyroid medication or low-iodine diet may have to be discontinued for 5 to 7 days and another serum total T4 measured to determine the true severity of the cat’s hyperthyroidism 3. Chest radiography or cardiac ultrasonography (or both) should be performed if the cat has evidence of any clinically significant cardiac disease (especially pronounced heart murmur, arrhythmia, dyspnea, or jugular venous distention) In normal cats, the thyroid gland appears on thyroid scans as two well-defined, focal (ovoid) areas of radionuclide accumulation in the cranial to middle cervical region. The two thyroid lobes are symmetric in size and shape and are located side by side (Web Figure 21-1). On the scan, we expect the thyroid and salivary glands to be equally bright (a 1 : 1 brightness ratio). In addition to visual inspection, one can calculate the percent thyroidal uptake of radionuclide 99mTcO4– correlated with circulating thyroid hormone concentrations and provide an extremely sensitive means of diagnosing hyperthyroidism. Web Figure 21-1 Thyroid image of a cat with normal thyroid function. In normal cats, the thyroid gland appears on thyroid scans as two well-defined, focal (ovoid) areas of radionuclide accumulation in the cranial to middle cervical region. The two thyroid lobes are symmetric in size and shape and are located side by side. Activity in the normal thyroid closely approximates activity in the salivary glands, with an expected “brightness” ratio of 1 : 1. 1. First, thyroid scintigraphy helps confirm the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism, which is very useful in cats in which a thyroid nodule cannot be palpated. Because thyroid scintigraphy directly visualizes functional thyroid tissue and the “uptake” of the radioisotope can be estimated by determining the thyroid : salivary ratio, thyroid imaging can diagnose hyperthyroidism before laboratory tests are consistently abnormal (Web Figure 21-2). Thyroid scintigraphy is considered the gold standard for diagnosing mild hyperthyroidism in cats. Web Figure 21-2 Thyroid images of two cats with early hyperthyroidism. Both cats had serum concentrations of total T4 within the reference range limits, with slight elevations of their free T4 values. The cat on the left (A) has a unilateral left thyroid adenoma, whereas the cat on the right (B) has bilateral adenomas. In both cases, notice that the uptake of the radionuclide by the functional thyroid adenoma(s) is higher than the uptake by the cats’ salivary tissue. For both cats, a high thyroid : salivary ratio was calculated, diagnostic for hyperthyroidism. 2. Thyroid scintigraphy can also exclude the diagnosis of hyperthyroidism in euthyroid cats that have false-positive elevations in their serum T4 or free T4 values. Studies of cats with nonthyroidal illness (e.g., diabetes; renal, gastrointestinal, or liver disease) have shown that between 6% and 12% of these cats have falsely high serum free T4 values, despite the fact that they are not hyperthyroid. In addition, routine screening of an apparently healthy senior cat occasionally reveals laboratory abnormalities that include slightly high total or free T4 concentrations, consistent with mild hyperthyroidism. As with sick cats with falsely high free T4 values, however, no thyroid nodule can be palpated in many of these cats and thyroid imaging may fail to confirm hyperthyroidism. Therefore not every cat with a high total T4 or free T4 value is truly hyperthyroid, and treatment for hyperthyroidism would be contraindicated. 3. In addition to visualization of functional cervical thyroid nodules, thyroid scintigraphy is an excellent method for evaluating the size of ectopic thyroid tissue, which can be located anywhere from the base of the tongue to the heart (Web Figures 21-3 and 21-4). In addition, thyroid images can locate large tumors that gravity has pulled into the thoracic cavity, which cannot be palpated on physical examination. Web Figure 21-3 Thyroid image of a hyperthyroid cat with a single ectopic (intrathoracic) thyroid adenoma. Note the location of the adenoma within the thorax (arrow). The normal, nonadenomatous thyroid lobes are completely suppressed and are not visible (as indicated by ovals). This cat did not have any palpable thyroid enlargement. Web Figure 21-4 A and B, Thyroid images of a hyperthyroid cat with bilateral thyroid adenomas in the expected cervical location. In addition, note the ectopic thyroid tissue in the sublingual location (arrows). Although the cat’s cervical thyroid nodules could be palpated, the ectopic sublingual nodule was not palpable. 4. By providing a visual image of hyperfunctional thyroid tissue, thyroid scintigraphy allows for the determination of thyroid tumor mass or volume, which is useful in calculating each cat’s radioiodine dose. The goal of 131I therapy is to restore euthyroidism with a single dose of radiation without producing hypothyroidism. Recent research confirms that iatrogenic hypothyroidism contributes to the development of azotemia and shortened survival times in cats overtreated with radioiodine. To minimize the incidence of iatrogenic hypothyroidism, it is important to administer the lowest effective dose to each individual cat rather than giving a fixed dose of radioiodine to all cats. Again, thyroid scintigraphy provides an excellent method for evaluating the size of the hyperfunctional thyroid tissue, which aids in determining the proper dose to treat the individual hyperthyroid cat. 5. Thyroid scintigraphy also provides valuable information in the diagnosis and evaluation of hyperthyroid cats with thyroid carcinoma (Web Figure 21-5). Our latest studies suggest that, although thyroid carcinoma is rare in cats with recently diagnosed hyperthyroidism, the prevalence of carcinoma progressively increases in cats treated long term with antithyroid medications (Peterson and Broome, 2012a and 2012b). Of cats with more than 4 years of medical treatment, over 20% had scintigraphic evidence of thyroid carcinoma. The diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma can be challenging (even with histopathology), but without pretreatment scanning these cases would go undetected. Because of the large tumor volume associated with thyroid carcinoma, as well as the potential for local invasion and metastasis, most of these cats are treated with high doses of radioiodine (e.g., 30 mCi, 1100 mBq) in order to completely ablate all thyroid tissue, thereby curing the cat’s thyroid cancer (Web Figure 21-6). Web Figure 21-5 Thyroid image of a hyperthyroid cat with functional thyroid carcinoma. In addition to the two thyroid masses in the cervical location, there are at least two areas of tumor tissue within the thoracic cavity, with extension of the disease beyond the limits of the thyroid capsule. This represents regional metastasis characteristic of malignant disease.

Radioiodine for Feline Hyperthyroidism

Patient Selection and Preparation before Radioiodine Treatment

Thyroid Scintigraphy for Evaluation of Hyperthyroid Cats

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chapter 21: Radioiodine for Feline Hyperthyroidism

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue