Chapter 10 Ceruminous Diseases of the Ear

Histopathology of the External Ear Canal

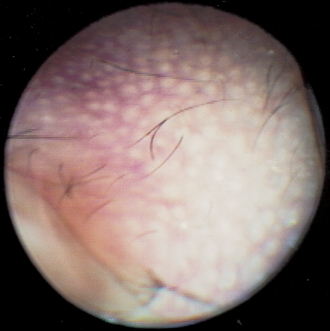

The epithelium of the external auditory meatus is composed of components similar to those of normal skin. The stratum corneum is the outermost layer; keratinocytes make up this layer of squamous anuclear cells. There are no rete ridges in the epithelium of the ear canal. The sebaceous glands are the outermost glands; they become progressively more numerous deeper into the meatus. Underlying the sebaceous glands are simple, coiled, tubular, apocrine glands called ceruminous glands, with ducts that open directly into hair follicles or onto the surface of the ear canal (Figure 10-1). During inflammatory reactions, sebaceous glands become hyperactive and hyperplastic; the ceruminous glands become dilated, thickened, and filled with secretions (Figure 10-2). Under normal physiologic conditions, ceruminous secretions (cerumen) combine with sebum produced by the sebaceous glands and epidermal debris to form earwax, the normal secretion of the ear.

Etiology of Ceruminous Otitis

When ceruminous glands and sebaceous glands of the ear canal become chronically irritated, the results are cystic dilation of ceruminous glands, hyperplasia, and increased activity of the overlying sebaceous glands. The excessive amount of cerumen produced by ceruminous glands forms a favorable medium for the growth of secondary bacteria and yeast. These organisms are normal flora of the ear and include Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., and Malassezia pachydermatis (see Chapter 9). With improper drainage and lack of air circulation (due to pendulous ears in some breeds), excessive growth of these organisms may occur within the ear canal.

Disorders of Keratinization

Primary Idiopathic Seborrhea

Ceruminous otitis can be due to an inherited or acquired keratinization defect. Inherited disorders include idiopathic primary seborrhea, commonly seen in West Highland White Terriers, American Cocker Spaniels, English Springer Spaniels, Basset Hounds, Irish Setters, Dachshunds, Chinese Shar-Peis, and German Shepherds. Primary idiopathic seborrhea, epidermal dysplasia of West Highland White Terriers, and lichenoid-psoriasiform dermatosis of English Springer Spaniels are examples of primary keratinization defects with ceruminous otitis externa. Secondary or acquired keratinization defects include vitamin A–responsive dermatosis, zinc-responsive dermatosis, and fatty acid deficiency.

Treatment.

Because ceruminous otitis is only the manifestation of a more serious problem, finding the underlying cause should be the clinician’s primary goal. Treatment of primary seborrhea should attempt to control the disease rather than produce a complete cure. Treatment of the ears should focus on (1) control of secondary infections and of production of scales and crust, and (2) reduction of inflammation. Frequent ear cleaning with appropriate topical medication can control the odor associated with this condition. Steroids, cytotoxic drugs, and retinoic acid have variable effects. Results with the use of synthetic retinoid (etretinate) in Cocker Spaniels and other breeds to treat idiopathic seborrhea are disappointing. In the Cocker Spaniel, for example, there is a reduction of scales, crust, and alopecia, but the ceruminous otitis is not responsive to this therapy. It is less effective in other breeds affected with this condition.

Endocrine Dermatosis

Hyperadrenocorticism.

The cutaneous manifestations of excessive serum cortisol are as follows:

Seborrhea dermatitis may manifest as ceruminous otitis with secondary bacterial or Malassezia infections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree