Rikke Buhl

Cardiac Murmurs

The equine practitioner is often challenged by determining the clinical significance of cardiac murmurs heard on auscultation. By nature, physiologic murmurs are common; therefore cardiac murmurs may be confusing, and it can be difficult to state the significance of the findings. Although most cardiac abnormalities are minor and do not influence performance, cardiovascular diseases can become significant and lead to reduced performance and a potentially fatal outcome. Without doubt, anamnesis and careful auscultation are the most important initial elements of the cardiovascular examination, and the overall sensitivity of auscultation for diagnosis of significant valvular diseases or congenital defects is high.

Classification of Cardiac Murmurs

Physiologic Murmurs

Physiologic murmurs, such as flow murmurs, are common in horses. Flow murmurs are caused by vibrations that result from the rapid ejection of a large volume of blood from the ventricles into the large arteries during systole. Similarly, the large inflow of blood into the ventricles in early diastole also may result in a murmur. Generally, these flow murmurs are short in duration and localized to a narrow area. Physiologic murmurs caused by systemic illness such as anemia, fever, dehydration, or endotoxemia disappear when the primary disease resolves.

The examiner should strive to distinguish physiologic from pathologic murmurs. By integrating the history and clinical examination, including careful auscultation, murmurs can often be diagnosed as physiologic and not assessed further. However, at times when the physiologic murmur has a high intensity (e.g., a systolic physiologic murmur heard in a horse with colic), the murmur can be confused with mitral valve regurgitation (MR). Also, functional ventricular filling murmurs in young racehorses can result in a loud early diastolic musical or squeaky murmur (commonly termed the 2-year-old’s squeak) that can be misinterpreted as aortic regurgitation. In these situations, further evaluation with echocardiography is warranted. The rest of this chapter focuses on the most commonly encountered pathologic murmurs that are caused by valvular or structural diseases in the heart.

Pathologic Murmurs

Acquired valvular dysfunction, in particular valvular regurgitation (also called valvular insufficiency), is a major cause of pathologic murmurs in horses. The etiology of this retrograde blood flow through the valve is not well defined, but dysfunction can occur in any part of the valve. Degenerative myxomatous changes of the valve annulus, leaflets, chordae tendineae, or papillary muscles are often reported to be causative. Physical training may also result in mild valvular regurgitation, not because of degenerative changes, but probably secondary to training-induced myocardial hypertrophy that leads to valvular insufficiency. Most of the latter types of regurgitations are diagnosed by color Doppler echocardiography and rarely by auscultation. Rupture of the chordae tendineae, bacterial endocarditis, and valvulitis are less commonly encountered causes of valvular regurgitation. It is important to note that valvular stenosis only rarely develops in horses. Congenital cardiac malformations also cause pathologic murmurs. Ventricular septal defect (VSD) is the most frequently recognized malformation in horses.

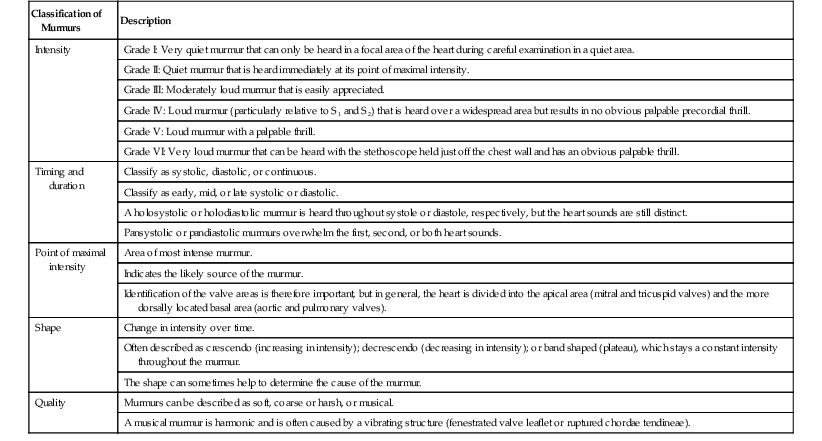

The magnitude and duration of the pressure difference between two cardiac chambers or between a chamber and the associated large artery influences the intensity, duration, and frequency of a pathologic cardiac murmur. Murmurs are classified and summarized (Table 122-1). In general, clinically significant murmurs are loud and long-lasting, but the intensity of the murmur is related not only to the volume of regurgitant blood but also to the driving pressure and the conformation of the horse. Hence grading of severity by auscultation alone is often not sufficient. Further classification of severity and determination of the exact diagnosis and prognosis require additional diagnostic tests.

Diagnostic Tests

Echocardiography

Ultrasonographic examination of the heart (echocardiography) is the most important diagnostic modality used for evaluating cardiac murmurs. Two-dimensional echocardiography and M-mode echocardiography are used to visualize structure and function of the cardiac chambers, valves, and pericardium, whereas Doppler echocardiography detects the direction and velocity of blood flow. Because detection of turbulent blood flow is often important in explaining the source of a murmur, the high sensitivity of color Doppler echocardiography is the gold standard for assessing valvular regurgitation.

Electrocardiography

Electrocardiography is an important tool when it is suspected that a murmur is a consequence of cardiac hypertrophy. For example, a horse with aortic regurgitation may develop ventricular arrhythmias secondary to left ventricular dilatation and reduced perfusion of the coronary arteries, which can negatively affect performance capacity and the safety of riding the horse. Often these arrhythmias only occur intermittently; therefore continuous Holter monitoring over 24 or 48 hours is warranted. Also, telemetric ECG during exercise testing may be relevant, with the purpose of studying exercise-induced cardiac arrhythmias.

Exercise Testing

It can be challenging to determine whether poor performance is related to the cardiovascular, pulmonary, or musculoskeletal system or is simply caused by insufficient training and lack of fitness. Exercise testing can help resolve this question and is pivotal in assessing clinical significance of cardiac murmurs because valvular regurgitations may predispose to development of cardiac arrhythmias during exercise. At present, there is no standard exercise test for horses, so the test chosen will vary depending on the horse being examined and whether it is necessary to detect subtle cardiovascular diseases or diagnose severe arrhythmias. For these reasons, under clinical settings, exercise testing provides a qualitative assessment rather than a quantitative measure of exercise capacity. Attention should be paid to whether the horse has the ability to perform the work requested, to the heart rate response to exercise and recovery time, and to the development of a cardiac arrhythmia during or after exercise. For diagnostic or prognostic purposes, it would be useful to determine whether cardiac murmurs increase or decrease in intensity during exercise, but this is very difficult to standardize. As a general rule, minor valvular regurgitations tend to disappear during exercise, whereas more severe regurgitations are unchanged or even worsened in intensity.

Laboratory Testing

Complete blood count and serum biochemistry are rarely useful in diagnosing cardiac murmurs. Although blood concentrations of cardiac injury biomarkers, such as cardiac troponin I (cTnI), T (cTnT), and C (cTnC), as well as the myocardial isoform of creatine kinase (CK-MB) and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), have been measured in horses, no standardized laboratory tests exist on which to base diagnosis and prognosis.

Systolic Murmurs

Mitral Valve Regurgitation

Mitral valve regurgitation is one of the most commonly encountered valvular regurgitations that lead to reduced performance in horses. There is no breed, age, or sex predisposition, but it is rarely diagnosed in foals or yearlings. The clinical presentation of horses with MR varies with severity. Often the systolic murmur is an incidental finding in horses presented for prepurchase or general clinical examination, and these horses have no clinical signs of heart disease. Mitral valve regurgitation is also diagnosed in cases of poor performance. In severe cases, horses are presented with signs of heart failure.

The clinical examination will reveal a systolic murmur (grades II to V of VI). Typically, the murmur is holosystolic or pansystolic, but duration and intensity depend on the atrioventricular pressure difference and on the direction and volume of retrograde blood flow. The point of maximal intensity (PMI) will most often be at the mitral area and directed dorsally toward the aortic area. In most cases, this is the only abnormal finding in the resting horse. In a minority, depending on MR severity, tachycardia, tachypnea, distension or pulsation of the jugular veins, dependent edema, increased respiratory sounds, and in the case of severe heart failure, nasal froth from pulmonary edema and prolonged capillary refill time, may be present. Initially, this may only happen during times of high demand, such as with exercise, but it can develop further and become permanent in the resting horse. Because intermittent or continuous cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation or atrial premature complexes can occur, exercise electrocardiography or Holter monitoring is recommended.

For final diagnosis and gradation of MR severity, echocardiography is recommended. With increasing severity, the amount of regurgitant turbulent blood flowing increases and covers an increasingly larger part of the left atrium (see Color Plate 122-1). When MR becomes hemodynamically significant, it results in volume overload in the left side of the heart, which eventually results in enlargement of the left atrium as well as the left ventricle, with the latter resulting in a rounder appearance that more or less resembles the ventricle of a dog. If the volume overload exceeds the compensatory mechanisms of the blood vessels, pulmonary vascular pressures increase, which results in increased right ventricular afterload and a dilated pulmonary artery, right ventricle, and atrium.

The prognosis for horses with MR varies according to the described findings. For horses with signs of heart failure, severe enlargement of the heart, or severe cardiac arrhythmias like atrial fibrillation, the prognosis for athletic performance or use as a pleasure horse is poor. For horses with less marked changes as detected by echocardiography and few or no clinical signs, the prognosis is usually good, depending on the performance level of the horse (the cardiovascular demands of a dressage horse are minimal, for example, compared with those of a racehorse). However, the progression is unpredictable, so the significance of MR for future athletic use is difficult to determine at the time of examination. Therefore a follow-up examination after 6 to 12 months is recommended to evaluate progression of the disease.

In most instances, a specific treatment is not indicated, and management is aimed at periodic monitoring of cardiac function and client education. If the horse develops heart failure, treatment may be warranted. However, treatment of horses in heart failure is generally not recommended except for some breeding horses or when the owner wishes to keep the animal. Acute supportive treatment of horses in heart failure includes diuretics to reduce vascular congestion (furosemide, 1 to 2 mg/kg, IV, every 12 hours) combined with a vasodilator drug such as an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (enalapril, 0.5 mg/kg, PO, every 12 hours; or quinapril, 0.25 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours). If the horse has severe tachycardia, digoxin can be given at a dosage of 0.0022 mg/kg intravenously every 12 hours, or 0.011 mg/kg orally every 24 hours.

Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation

Tricuspid valve regurgitation (TR) is the most commonly detected cardiac murmur in racehorses but is probably of no significance in nearly all instances, even in horses with severe TR. There is no breed, age, or sex predisposition, but in general it is rarely diagnosed in foals or yearlings. The clinical presentation of horses with TR is often normal, with the murmur being detected as an incidental finding. Because the murmur is detected on the right side of the thorax, where auscultation of the heart is more challenging, some regurgitation may be missed. Tricuspid regurgitation may also be seen in horses with poor performance; because TR is unlikely to be causative, the clinician should rule out other reasons for poor performance before associating it with the TR.

The clinical examination will reveal a systolic murmur of grades II to V of VI intensity. The murmur may be holosystolic or mid to late systolic. The PMI is at the tricuspid area, which is at the right side of the thorax where the heart sounds are most clearly heard; the murmur often radiates dorsally. Tricuspid regurgitation is probably the type of regurgitation in which the murmur intensity best correlates with the volume of regurgitant blood flow. If a loud murmur is heard over the right hemithorax, it is advisable to repeat auscultation of the left hemithorax craniodorsally over the pulmonary area to avoid overlooking a ventricular septal defect (described later). In cases of severe TR, jugular distension and pulsation can be observed, with prominent pressure waves extending up the jugular vein for more than 10 cm during systole (the head of the horse should be held in a neutral position for this determination, not at a level lower than the heart). If bacterial endocarditis is present or if right-sided heart failure has developed secondary to pulmonary hypertension from pulmonary disease or left-sided heart failure, signs of heart failure can be observed. Rarely, cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation may accompany TR.

Echocardiography is indicated to grade TR severity. The regurgitant blood flow is visualized by color Doppler echocardiography. Because the right ventricle and atria have variable geometry and are less uniform in size than the left side of the heart, it is challenging to quantify enlargement of the chambers. The size of the right atrium and ventricle can only be estimated subjectively by comparison with the left ventricle. The contribution of pulmonary hypertension to TR can be assessed indirectly with pulse-wave or continuous-wave Doppler echocardiography, by measuring the peak velocity of the tricuspid regurgitant blood flow.

The prognosis for horses with TR is generally good, and only rarely does TR affect performance unless right-sided heart failure exists. When heart failure is present, therapy as described for MR may be considered. Follow-up examinations usually are not required unless arrhythmias are present or there is suspicion of poor performance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree