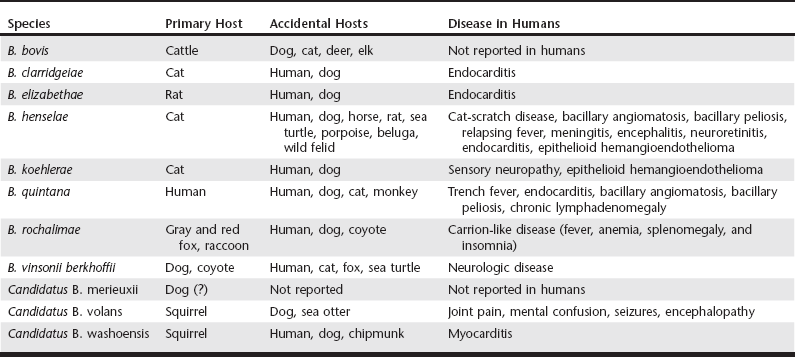

Chapter 269 Currently the genus Bartonella comprises at least 30 species and subspecies of fastidious gram-negative bacteria. They are transmitted by hematophagous arthropods and capable of infecting and causing a chronic and persistent intraerythrocytic bacteremia in a wide variety of terrestrial and marine hosts. The identification of Bartonella DNA from a 4000-year-old human tooth and from 800-year-old cats demonstrates that these organisms have coevolved over the centuries with mammalian hosts. Overall, Bartonella spp. are not species specific, but selected bacterial species have adapted to specific mammalian hosts, such as B. henselae and B. clarridgeiae to cats; B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and B. rochalimae to domestic dogs and wild canids; B. bovis to cattle; B. washoensis to ground squirrels; and B. quintana to humans. Consequently, these adapted species generally cause limited clinical manifestations in their preferred hosts, in spite of persistent bacteremia. Pathologic effects are more common in immunosuppressed hosts or when Bartonella spp. infect a non-adapted accidental host, resulting in a wide variety of clinical manifestations. However, the low levels of bacteremia and frequent lack of specific antibody response in immunocompetent cats, dogs, and human patients make the diagnosis a challenge (Boulouis et al, 2005; Breitschwerdt et al, 2010). In recent decades, the evolution of laboratory diagnostic techniques has facilitated the identification of several Bartonella spp. infecting dogs, eight of them capable of infecting humans as well. Although the role of dogs as reservoirs for human infection has not been defined, dog infection may be an important epidemiologic sentinel for human exposure because both share the same environment. Bartonellosis is an emerging infectious disease in human patients, with veterinarians and other professionals in frequent animal contact considered at-risk groups (Maggi et al, 2011). Eleven species, subspecies, or species candidatus of Bartonella have been reported from dogs (Table 269-1): B. bovis, B. clarridgeiae, B. elizabethae, B. henselae, B. koehlerae, B. quintana, B. rochalimae, B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii, Candidatus B. merieuxii, Candidatus B. volans, and Candidatus B. washoensis. Worldwide, the two most frequent species in dogs are B. henselae and B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii. Dogs are considered the primary host of B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii, and they also may be reservoirs for B. rochalimae. TABLE 269-1 Species of Bartonella Detected in Dogs, Other Accidental Mammalian Hosts, and Reported Syndromes in Humans B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii has been identified as an important cause of endocarditis in dogs and also has been associated with myocarditis and anterior uveitis. Historically, this species was considered the most frequent species infecting dogs. Four genotypes of B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii have been described, based upon analysis of blood samples from coyotes, dogs, foxes, and humans. All four genotypes have been reported in dogs with endocarditis and a range of other clinical manifestations, but genotypes I, III, and IV are found infrequently. Antigenic differences among genotypes may explain negative serology titers in some infected dogs (Breitschwerdt et al, 2010; Maggi et al, 2006). B. rochalimae was first isolated in 2007 from an American woman who became severely ill two weeks after returning to the United States from Peru, where she experienced multiple insect bites. Infection with B. rochalimae also was found in a dog with endocarditis in San Francisco, California, in a sick dog from Greece, and in 7.3% of 205 asymptomatic dogs in Peru (Diniz et al, 2012). The epidemiology of this organism is still limited, but gray foxes and raccoons may be the natural reservoir in California and red foxes in Europe and Israel (Henn et al, 2009). In addition, an experimental infection of two dogs, five cats, and six guinea pigs with B. rochalimae demonstrated that only dogs became highly bacteremic without any disease expression, suggesting that dogs could be the natural reservoir for this species (Chomel et al, 2009a). Other species of Bartonella were described infecting dogs (see Table 269-1). The most common disease manifestation reported in these cases included endocarditis, followed by hepatic disease, weight loss, and, in one case, sudden death. Recently, 37% of 97 stray dogs in Iraq were found to be infected with a new species named Candidatus Bartonella merieuxii; however, its pathogenicity for dogs is still unknown (Chomel et al, 2012). Bartonella spp. have been found in all continents except Antarctica. Unlike in cats, the prevalence of Bartonella spp. in dogs is generally low. The epidemiology of these organisms is diverse in tropical areas, but low prevalence has been detected in dogs in subtropical regions. In Thailand, exposure to B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii, determined by antibody detection, was reported in 39% (19/49) of sick dogs. Similarly, 38% of 147 dogs from Morocco were seropositive for B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii. In contrast, seroprevalence of 10% or less for B. henselae or B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii was reported from southeastern Brazil, Granada, Hawaii, the United Kingdom, Israel, Taiwan, and Japan. Bacteremia, documented by PCR amplification of Bartonella DNA, was reported in 16.7% (9/54) of healthy dogs in Korea, 11.6% (7/60) of healthy dogs in southern Italy, 6.3% (5/80) of dogs in Algeria, 1.4% (1/73) of dogs in Grenada, and 1% (2/198) of sick dogs in Brazil. In the United States, a study involving 663 dogs from 11 states located in the northeastern, midwestern, or southern United States detected 61 bacteremic dogs (9.2%) infected with one species and 9 dogs (1.4%) coinfected with more than one species of Bartonella (Breitschwerdt et al, 2010; Chomel et al, 2010). Several arthropod vectors including biting flies, fleas, keds, lice, sandflies, and ticks have been implicated in the transmission of Bartonella spp. among mammals. The mode of transmission in dogs is not well established, but epidemiologic evidence supports the role of ticks and fleas. Bartonella DNA was detected in Ixodes spp. and Rhipicephalus sanguineus (brown dog tick) collected in North America, Europe, and Asia. Transmission of the bacterial pathogen from fleas occurs through inoculation of contaminated flea feces into the skin via a scratch or bite. Consequently, heavy flea exposure, heavy tick exposure, cattle exposure, and a rural environment are risk factors for Bartonella spp. infection (Chomel et al, 2010). Once Bartonella spp. gain access to the bloodstream, they infect a primary niche outside of circulating blood, possibly vascular endothelial cells or CD34+ progenitor cells in the bone marrow. This approach provides a potentially unique strategy for immediate access to erythrocytes, ideal for bacterial persistence within the circulatory system. Bartonella spp. also can infect dendritic cells, microglial cells, monocytes, and macrophages. Cell invasion by Bartonella spp. is mediated by two groups of virulence factors: adhesins and the type IV secretion system (T4SS). Adhesins mediate adhesion to the extracellular matrix of mammalian host cells, whereas the T4SS is capable of transporting DNA and effector proteins to the target host cell. Bartonella adhesin A (BadA) mediates bacterial adherence to endothelial cells and extracellular matrix proteins and triggers the induction of angiogenic gene programming. The VirB/VirD4 T4SS is responsible for inhibition of host cell apoptosis, bacterial persistence in erythrocytes, and endothelial sprouting. The Trw T4SS system of Bartonella spp. mediates host-specific adherence to erythrocytes. In vitro, the peak invasion of canine erythrocytes by B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii occurs after 48 hours postinoculation (PI). In vivo, approximately on day five PI, large numbers of bacteria are released into the bloodstream, where they bind to and invade mature erythrocytes. Bacteria then replicate in a membrane-bound compartment until reaching a critical number. For the remaining life span of the erythrocytes, the intracellular bacteria remain in a nondividing state. Continuous replication of the pathogen in the primary niche causes erythrocyte infection waves at approximately 5-day intervals, causing persistent bacteremia to facilitate the acquisition of the organism by the vector. Experimental infection of dogs with B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii induced immunosuppression, characterized by sustained suppression of peripheral blood CD8+ lymphocytes. Immunosuppression caused by Bartonella infection may predispose the host to opportunistic infections, including infection by other pathogens transmitted by the same vector; however, this hypothesis has not yet been proven (Franz and Kempf, 2011). The cyclic shedding of Bartonella spp. from the primary niche into the bloodstream facilitates the distribution of the organisms throughout the body, with consequent involvement of numerous cell types, many organ systems, and a wide range of disease manifestations (Box 269-1) and diagnoses (Box 269-2). Lesions may occur in the heart, liver, lymph nodes, joints, eye, nasal cavity, CNS, skin, and subcutaneous tissue. Unfortunately, clinical signs of Bartonella infection in dogs cannot be discriminated from other tick-borne infections, with the most frequent signs fever (40%), lethargy (40%), weight loss (34%), anorexia (32%), and lymphadenopathy (30%). Weight loss was significantly associated with Bartonella spp. infection in dogs when compared with sick dogs suspected of other vector-borne diseases (Perez et al, 2013). Endocarditis is a common clinical finding in Bartonella-infected dogs. Endocarditis is documented more frequently in large-breed dogs with a predisposition for aortic valve involvement; however, 20% of cases involve the mitral valve or multiple valves. Endocarditis resulting from B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii infection is the most commonly reported; however, endocarditis resulting from B. clarridgeiae, B. henselae, B. koehlerae, B. quintana, B. rochalimae, or B. washoensis infection was reported in a limited number of dogs. The clinical abnormalities commonly reported in dogs with endocarditis resulting from Bartonella spp. are murmurs (89%), fever (72%), leukocytosis (78%), hypoalbuminemia (67%), thrombocytopenia (56%), elevated liver enzymes (56%), lameness (43%), azotemia (33%), respiratory abnormalities (28%), and weakness and collapse (17%) (Breitschwerdt et al, 2010; Chomel et al, 2009b).

Canine Bartonellosis

Bartonella Species in Dogs

Epidemiology

Transmission and Risk Factors

Pathogenesis

Clinical Presentation

Canine Bartonellosis