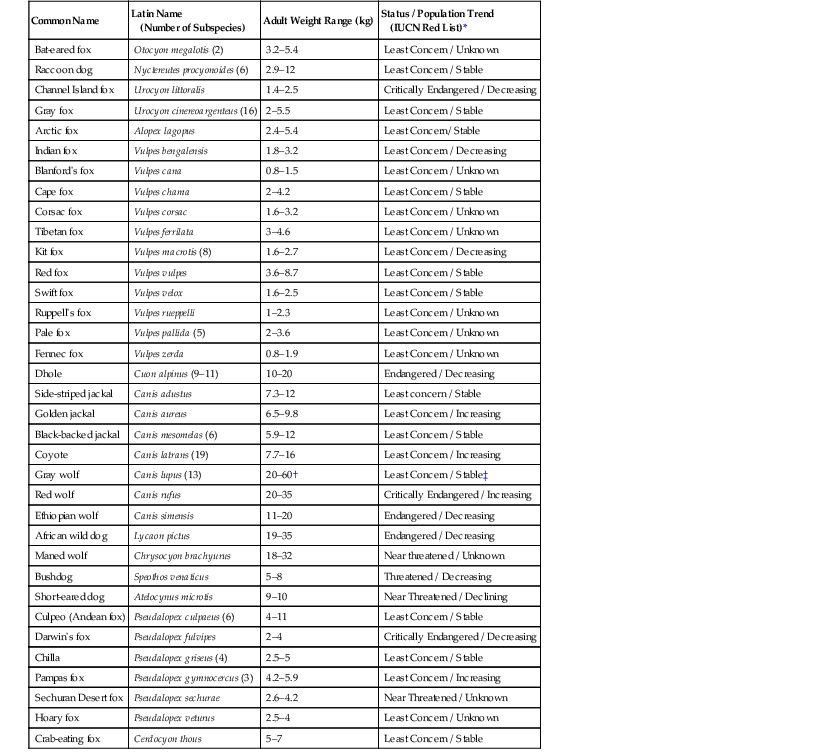

Luis R. Padilla, Clayton D. Hilton The family Canidae currently includes 35 species of dogs, wolves, coyotes, jackals and foxes39 (Table 46-1), and a larger number of subspecies whose status is under constant revision. All members are part of the subfamily Caninae, which is the only extant group of three subfamilies in the fossil record of this family. Evidence suggests that the Eastern wolf should be considered a distinct wolf species (Canis lycaon) that is more closely related to the red wolf (C. rufus) than to the gray wolf of which it has been historically considered a subspecies (C. lupus lycaon).21 The most common canid, the domestic dog, derived from the gray wolf (C. lupus) through close association and interactions with humans approximately 12,000 years ago. The dingo and the New Guinea singing dog are considered feral populations of domestic dogs that have reverted to a wild status and are thus considered subspecies of C. lupus. TABLE 46-1 Canid Species and Population Status39 * International Union for the Conservation of Nature: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed February 1, 2013. † Significant size variation occurs between subspecies of Canis lupus. ‡ Status reflects species as a whole; the status of individual subspecies is at varying risks of extinction, and populations are not stable. Canidae is one of the most geographically widespread carnivore families; at least one wild species is present on each continent, except Antarctica. The red fox, which is present on five continents, and the gray wolf, present on three, span some of the largest geographic ranges of any terrestrial mammal. Canids have diversified to inhabit a wide variety of habitat types. Species occur in desert environments, savannas, tropical and temperate forests, coastal areas, and arctic environments. Individual species range in size from members of the Vulpes genus weighing 1 kilogram (kg) or less, to subspecies of the gray wolf exceeding 60 kg. Sexual dimorphism occurs in a majority of species, and males are typically larger. Some species are solitary, some form monogamous or seasonally monogamous pairs, whereas others have large, complex packs of multiple generations within a social unit. Large packs of some species make formidable and efficient units capable of preying on larger animals and fending off predators. Many smaller canids forage for prey alone, in pairs, or in small groups. Some species such as the coyote (C. latrans) exhibit extreme social flexibility, being capable of existing as solitary individuals, in pairs, or in large complex packs. A large proportion of the recognized wild canid species currently face the threat of extinction,39 and numerous subspecies are at risk even when the species may be stable as a whole. Many populations have been extirpated from portions of their historic range. Persecution by humans, the introduction of diseases from domestic dogs, habitat disturbance, and hybridization with domestic or wild canids pose significant threats to the continued survival of many species. At least one species (the Falkland Island wolf, Dusicyon australis) has become extinct within the last 150 years (in 1876) as a result of direct human pressure. Canids exhibit characteristic skull features, including the medial position of the internal carotid artery between the entotympanic and petrosal arteries, loss of the stapedial artery, and an inflated entotympanic bulla divided by a partial septum. The insertion point of the digastric muscle is widened in several canid taxa, forming a subangular lobe on the horizontal ramus of the mandible, which has been hypothesized to be a functional adaptation for rapid jaw movement.3 The subangular lobe is prominent in foxes with complex molars, including the genera Urocyon, Otocyon, and Cerdocyon, and in raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes spp.).42 The dental formula of Canidae is incisors (I) 3/3, canines (C) 1/1, premolars (P) 4/4, molars (M) 2/2 in all but three genera (Speothos, Cuon, and Otocyon). Although not unique among carnivores, the maxillary fourth premolar and the mandibular first molar of canids are modified to oppose each other and maximize the shearing efficiency when biting into prey. The modified teeth are termed carnassial or sectorial teeth. Specialized lateral nasal glands provide moisture for evaporative cooling during panting, which is the primary heat loss mechanism in canids. Sweat glands are only present in the footpads and are not significant to heat dissipation. Cutaneous muscles may control the pelage and serve an important thermoregulatory role. Seasonal molt of the pelage of temperate species is an important adaptation to coping with temperature extremes. Canids have four digits in each of the hindlimbs and five in each of the forelimbs, although the first digit may be rudimentary. The African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) is the exception, with only four digits on each limb. Many of the larger canids are adapted for traveling long distances as they forage or chase prey, and during seasonal migrations. These species have significant aerobic and anaerobic capabilities for running at high speeds over long distances while chasing prey. Canids have refined senses of hearing, smell, and vision, which are key to maintenance of complex social systems, communication between conspecifics, and maintaining territories. Olfactory cues from urine, feces, and anal and supracaudal glands have an important role in canid social interactions. The supracaudal gland, commonly called the tail gland or the violet gland because of its production of volatile terpenes similar to those produced by flowers in the Violaceae family, is a specialized scent gland located on the dorsal surface of the tail. The tail gland is located at the level of the seventh to ninth caudal vertebrae and is most developed in solitary fox species (such as Artic, red, and corsac foxes), less developed in jackals,38 and absent in African wild dogs.18 Powerful hair erector muscles associated with the tail gland contract to release a lipoprotein onto the surface of the skin,38 which plays a role in species and individual recognition. The raccoon dog (N. procyonoides) and other species may undergo a period of seasonal torpor or hibernation, characterized by decreased basal metabolic rates and lower levels of cortisol, insulin, and thyroid hormones.23 The African wild dog lacks variation at the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which is a fundamental component of the immune response of all vertebrate species and may be the result of population bottlenecks experienced by this species.24 In a family with a broad range of body sizes, occupying all possible habitats and maintaining a diversity of social systems, it is nearly impossible to standardize the ideal housing requirements for all species. Guidelines for captive housing space have been established for most canid species by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.35 An ideal enclosure takes into account overall holding area, size of the social group being housed, reproductive status of the group, and complexity of the area to elicit and maintain species-appropriate behaviors. The shape of an enclosure must allow animals to fully use the space, allow for proper interindividual distances, and provide flexibility in managing social groups, whose hierarchy and dynamics may change over time. Complex environmental features in enclosures stimulate the natural display of species-appropriate behaviors and likely minimize stress levels. Features in enclosures should allow for social species housed in groups to separate themselves, as needed, in cases of aggression and for packs to display a healthy behavioral repertoire. Gunnite and concrete wall enclosures may create undesirable acoustics that may be disturbing to many canids. Visual barriers and natural plantings provide cover and shade and also serve to muffle unwanted sounds. Enclosures should not have sharp corners, as these may facilitate upward propulsion and climbing. Animals running along a fence line may reach a corner and may jump upward and fall or do back flips, often injuring themselves. Sharp corners may be difficult for individuals to maneuver when running and may result in traumatic injuries to the skull, face, or neck. Spiral hindlimb fractures occurring in wolves jumping straight up in a corner and landing on one leg have been documented. Additionally, sharp corners may create conditions that provide a subordinate or incompatible individual with no means of escaping an aggressor. Enclosures should incorporate a holding space and additional holding areas for temporary holding or transfer. For large canids, where single-sex group of two animals or a nonbreeding pair is housed, the primary enclosure should be 5000 square feet (465 square meters [m2]), and an additional 1000 square feet (93 m2) per additional animal.35 Maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus) in this social setting require more space (10,000 square feet [930 m2]). Enclosures housing two large canids or a nonreproductive pair should have at least two holding pens of 200 square feet (19 m2) each.35 Large canids housed as a single generation per breeding enclosure should have 10,000 square feet (930 m2) and at least three holding pens of 200 square feet (19 m2) each.35 Enclosures intended to serve as multigenerational breeding areas need a minimum of 10,000 square feet (930 m2), plus a secondary enclosure of 5000 square feet (465 m2) and at least three holding pens of 200 square feet (19 m2) each. Enclosures holding groups for potential reintroduction to the wild need larger areas (20,000 square feet [1,860 m2]) plus a secondary enclosure of 5000 square feet (465 m2), and at least three holding pens of 200 square feet (19 m2) each, and special attention must be paid to the management practices and location of the enclosures to maintain wild behaviors and avoid imprinting on humans.35 Minimum space recommendations for small canids vary by species and social structure. Primary enclosure areas should be at least 6.5 feet (ft.) × 6.5 ft. × 5 ft. tall (2 m × 2 m × 1.5 m) for one or two animals, 10 ft. × 10 ft. × 5 ft. tall (3 m × 3 m × 1.5 m) for three animals, and 13 ft. × 13 ft. × 5 ft. tall (4 m × 4 m × 2 m) for family groups with up to five offspring. These guidelines are currently under revision, but these dimensions should be exceeded, whenever possible, and attention paid to the space layout, complexity, and social needs of the species. Minimum housing guidelines set for domestic dogs by the Animal Welfare Act of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), section 3.6(c)(1), are not sufficient for all wild canids and should be exceeded. Canids are proficient diggers and skilled jumpers. When fences are used, fence posts should be buried properly to secure them. These “dig barriers” should be 6 to 12 inches underground and extend 3 feet toward the center of the enclosure to prevent a prolific digger from tunneling under it.35 Buried concrete barriers may be used underground instead of fencing. Enclosure perimeter barriers should be of appropriate height to prevent an animal from jumping over, and the top could be angled or covered to discourage animals from obtaining footing on the wall and propelling themselves upward. A containment height of 8 ft. is recommended for most large canids as long as the surface does not allow climbing. Many species may tolerate a wide range of ambient temperatures, but small canids may be less tolerant of temperature extremes when housed outside of their natural climate and require special attention. Tropical species such as maned wolves, bushdogs, and African wild dogs are less tolerant of cold temperatures compared with temperate species of similar size. Species housed outdoors should have access to dry den structures and bedding, as well as shelters that individuals may choose to use for protection from the wind or rain. A periparturient dam should have multiple choices of warm and dry whelping boxes, and attention should be paid to the breeding season and the time of year, as some species will give birth during the colder months in temperate areas. The diets of wild canids range from omnivory to strict carnivory, and some species consume primarily insectivorous or piscivorous diets. Bushdogs (Speothos venaticus), dholes (Cuon alpinus), and African wild dogs are highly carnivorous, whereas bat-eared foxes (Otocyon megalotis) are almost exclusively insectivorous in the wild. The Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis) is adapted to a diet that is based almost exclusively on rodents, and maned wolves are the most omnivorous of the large canids. The proportion of dietary components varies seasonally among omnivorous species, depending on prey or plant abundance and the breeding season. The daily caloric need of a large canid (22–32 kg) has been estimated at 1300 to 1800 kilocalories (kcal) metabolizable energy (ME) per day in a thermoneutral environment under moderate activity.35 Caloric needs should be adjusted on the basis of the life stage of the animal, activity and thermoregulatory needs, and body condition. As a general guideline, the daily ME requirements of adult domestic dogs have been estimated at 50 to 65 kcal/kg of body weight, approximately 120 kcal/kg for growing puppies, 200 kcal/kg for lactating females, and as high as 450 kcal/kg for heavy working dogs. Canid diets typically contain 20% to 28% protein, 5% to 18% fat, and 2% to 4% crude fiber.35 This formula is derived from domestic dog requirements. Although it is recognized that species-specific differences exist with regard to some of these needs, objective information is lacking for most species’ needs. Canine diets based on raw meat are commercially available and form the basis of captive diets for some species, whereas others may be maintained on dry kibble. Dietary intolerance manifested by gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances, skin reactions, poor pelage, and cachexia have been reported in individuals that are maintained on cereal-based or highly processed grain diets. Omnivorous canids probably require high amounts of dietary fiber and may benefit from the addition of natural fiber sources to their diet, including produce and fruit. Whole prey items (rodents, rabbits, chickens) or partial carcasses (bones, ox tails, legs, deer) are used to supplement captive diets, but they must be taken into account when calculating overall dietary needs and should not be offered to the degree whereby they offset a balanced diet. Feeding whole or partial carcasses of wild or domestic ungulates often is used to stimulate pack behaviors and for social enrichment. Caution should be exercised to ensure that the carcasses are fresh, free of parasitic or other diseases, and harvested by using methods that do not contain harmful substances (such as lead shot, euthanasia solution, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], or toxins). Additional caution should be exercised in areas where prion diseases (such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy [BSE] or chronic wasting disease [CWD]) are present, since carnivore species may be susceptible to prion-associated neurologic disease. The USDA Animal Welfare Act (Section 13, 9 CFR, Subsection F, Section 3.129) specifically discourages feeding roadkill to large felids but outlines guidelines for proper handling if it must be fed. The same guidelines are applicable to canids. If whole carcasses are fed to animals intended for reintroduction, only carcasses from natural prey species should be offered, and domestic animal carcasses should never be offered, as canids will likely learn to recognize the species offered as possible prey items.35 It has been suggested that the maned wolf has lower animal protein needs compared with other canids.35 Scat studies of wild maned wolves suggest that plant material may account for 50% of their diet, with small mammals, insects, and birds accounting for the rest.8 Taurine levels should be monitored in captive maned wolves, and supplementation may be necessary on an individual basis.8 A soy-based pelleted diet has been commercially developed specifically for captive maned wolves, and preliminary results of experimental feeding show improved fecal consistency and body condition scores. Small canids may be restrained manually or with the use of nets. The use of leather gloves is recommended, but these do not provide full protection against significant bite injuries to a handler. A towel may be used to temporarily immobilize a small canid, and the head may be restrained through the towel by placing a hand behind the head while supporting the body with the other hand. Muzzles designed for domestic dogs may be used for handler protection when handling, and soft cloth rope or cotton roll gauze may be used as an impromptu muzzle. Muzzles must be monitored so that placement allows for normal breathing and avoidance of hyperthermia and should only be used for short periods. Canids may be conditioned for restraint in squeeze cages, and relatively simple ones may be designed and built if none is commercially available. Animals also may be trained for voluntary restraint and to accept injections. Hyperthermia is a common phenomenon seen in restrained canids, and body temperatures reaching or exceeding 40° C (104° F) warrant intervention. Persistent or prolonged hyperthermia may have a fatal outcome and has been documented in some species, notably dholes. Treatment with intravenous cool fluids and external cooling is warranted to combat hyperthermia, but this should be done slowly and while continuing to monitor body temperature. Sedatives are indicated in the management of stress-related hyperthermia. Some canids are prone to developing exertional myopathies after prolonged restraint, and if the clinician suspects it, supportive treatment should be instituted immediately. Maned wolves may be physically restrained.15 Confined gray wolves and red wolves may be physically restrained by experienced crews by using “catch” poles and “Y”-shaped padded poles. A team of people may enter an enclosure and exploit these species’ typical aversion to humans, forming a line and funneling the animal into either a corner of an enclosure or a den box. When approached, the animals will often cower, allowing for restraint with a catch pole placed loosely around the neck. Rigid but padded “Y”-shaped poles may be gently, but firmly, placed over the hips and shoulders to prevent an animal from jumping back or rolling while restrained by the catch pole (Figure 46-1). This type of restraint may be used for limited examinations, ultrasonography, blood collection, vaccination, or administration of intravenous injections. This technique is less effective and potentially dangerous when attempting to restrain hand-raised animals and individuals that have no aversion to humans, as they may resist restraint or attempt to attack when cornered and is not recommended for other large canid species (such as African wild dogs). Chemical restraint is recommended for prolonged or invasive procedures involving most large canids. Trapping is a tool used for the management, relocation, and study of wild canid populations. Box traps have been successfully used for trapping wild canids and are considered more humane and less stressful than other alternatives47 but are less effective for capturing the majority of wild canid species. Foothold traps (metal “jaw” traps and cable “noose” restraint devices)6 are used to capture wild canids, specifically wolves, foxes, and dholes, although their use has been outlawed in some countries. Traps should be properly padded and inspected to ensure proper functioning and minimal risk to the animal. Every consideration should be made for humane usage and exclusion of nontarget species. Foothold traps may cause injuries to the feet, legs and teeth,32 and individuals may develop hyperthermia or myopathy if restraint is prolonged. When initially restrained, some animals may actively dig and pull against the trap and may self-mutilate in trying to escape. If multiple traps are set within a short distance, an animal may be caught in more than one trap, or the mechanism may close around nontarget body parts as the animal rolls, pulls, and tries to escape from the primary restraint. The use of remote monitoring devices (e.g., motion sensors, cameras, and remote alarms that link to personal communication devices) has greatly improved the ability to minimize restraint time, and their use is reccommended.22 The use of tranquilizer trap devices has been considered for the capture of some canid species.37 A large number of anesthetic protocols have been used for the chemical restraint of canid species.1,7,11,13,19,23,46 Table 46-2 summarizes some species-specific suggested anesthetic protocols, but readers should consult a more thorough source23 for specific considerations. In addition, some of these protocols have been used extensively in other canid species despite lack of documentation in the peer-reviewed literature, and clinicians should use a solid understanding of drug mechanisms and sound judgment to extrapolate and use in appropriate situations. TABLE 46-2 Select Injectable Anesthetic Combinations Applicable to Canid Species

Canidae

General Biology

Common Name

Latin Name

(Number of Subspecies)

Adult Weight Range (kg)

Status / Population Trend

(IUCN Red List)*

Bat-eared fox

Otocyon megalotis (2)

3.2–5.4

Least Concern / Unknown

Raccoon dog

Nyctereutes procyonoides (6)

2.9–12

Least Concern / Stable

Channel Island fox

Urocyon littoralis

1.4–2.5

Critically Endangered / Decreasing

Gray fox

Urocyon cinereoargenteus (16)

2–5.5

Least Concern / Stable

Arctic fox

Alopex lagopus

2.4–5.4

Least Concern/ Stable

Indian fox

Vulpes bengalensis

1.8–3.2

Least Concern / Decreasing

Blanford’s fox

Vulpes cana

0.8–1.5

Least Concern / Unknown

Cape fox

Vulpes chama

2–4.2

Least Concern / Stable

Corsac fox

Vulpes corsac

1.6–3.2

Least Concern / Unknown

Tibetan fox

Vulpes ferrilata

3–4.6

Least Concern / Unknown

Kit fox

Vulpes macrotis (8)

1.6–2.7

Least Concern / Decreasing

Red fox

Vulpes vulpes

3.6–8.7

Least Concern / Stable

Swift fox

Vulpes velox

1.6–2.5

Least Concern / Stable

Ruppell’s fox

Vulpes rueppelli

1–2.3

Least Concern / Unknown

Pale fox

Vulpes pallida (5)

2–3.6

Least Concern / Unknown

Fennec fox

Vulpes zerda

0.8–1.9

Least Concern / Unknown

Dhole

Cuon alpinus (9–11)

10–20

Endangered / Decreasing

Side-striped jackal

Canis adustus

7.3–12

Least concern / Stable

Golden jackal

Canis aureus

6.5–9.8

Least Concern / Increasing

Black-backed jackal

Canis mesomelas (6)

5.9–12

Least Concern / Stable

Coyote

Canis latrans (19)

7.7–16

Least Concern / Increasing

Gray wolf

Canis lupus (13)

20–60†

Least Concern / Stable‡

Red wolf

Canis rufus

20–35

Critically Endangered / Increasing

Ethiopian wolf

Canis simensis

11–20

Endangered / Decreasing

African wild dog

Lycaon pictus

19–35

Endangered / Decreasing

Maned wolf

Chrysocyon brachyurus

18–32

Near threatened / Unknown

Bushdog

Speothos venaticus

5–8

Threatened / Decreasing

Short-eared dog

Atelocynus microtis

9–10

Near Threatened / Declining

Culpeo (Andean fox)

Pseudalopex culpaeus (6)

4–11

Least Concern / Stable

Darwin’s fox

Pseudalopex fulvipes

2–4

Critically Endangered / Decreasing

Chilla

Pseudalopex griseus (4)

2.5–5

Least Concern / Stable

Pampas fox

Pseudalopex gymnocercus (3)

4.2–5.9

Least Concern / Increasing

Sechuran Desert fox

Pseudalopex sechurae

2.6–4.2

Near Threatened / Unknown

Hoary fox

Pseudalopex veturus

2.5–4

Least Concern / Unknown

Crab-eating fox

Cerdocyon thous

5–7

Least Concern / Stable

Unique Anatomic Features

Special Housing Requirements

Feeding

Restraint and Handling

Species

Suggested Combination

Arctic fox (Alopex lagopus)

Ketamine (2.5 mg/kg), Medetomidine (0.05 mg/kg) IM6

Tiletamine-zolazepam (10 mg/kg) IM6

Golden jackals (Canis aureus)

Ketamine (1.8–2.4 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.09–0.11 mg/kg) IM15

Medetomidine (0.07–0.1 mg/kg), midazolam (0.39–0.55 mg/kg) IM15

Coyotes (Canis latrans)

Ketamine (4 mg/kg), xylazine (2 mg/kg) IM6

Ketamine (3–4 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.04–0.07 mg/kg) IM

Telazol (10–11 mg/kg) IM6

Gray wolves (Canis lupus)

Ketamine (3–4 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.06–0.08 mg/kg) IM6

Medetomidine (0.04 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg), ketamine (1 mg/kg) IM

Ketamine (5–10 mg/kg), midazolam (0.1–0.4 mg/kg) IV (after manual restraint)

Ketamine (4–10 mg/kg), xylazine (1–3 mg/kg) IM6

Telazol (10–13 mg/kg) IM (for helicopter captures)6

Red wolves (Canis rufus)

Ketamine (2 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.02 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg) IM6

Medetomidine (0.04 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg) IM, supplement with IV diazepam (0.2 mg/kg) or ketamine (1 mg/kg)6

Telazol (5–10 mg/kg) IM6

Ethiopian wolves (Canis simensis)

Telazol (2–7 mg/kg) IM23

Maned wolf (Canis brachyurus)

Medetomidine (0.04 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg) IM

Dexmedetomidine (0.02 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg) IM

Ketamine (2.5 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.08 mg/kg) IM23

Ketamine (6–9 mg/kg), xylazine (0.5–2 mg/kg) IM23

Telazol (3–5 mg/kg)23

Dhole (Canis alpinus)

Telazol (2 mg/kg), ketamine (2 mg/kg)

Telazol (4 mg/kg)16to (10 mg/kg)6 IM

African wild dog (Lycaon pictus)

Medetomidine (0.04–0.06 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.18–0.3 mg/kg), midazolam (0.18–0.4 mg/kg) IM11

Ketamine (1.5 mg/kg)18 to (5 mg/kg)6, medetomidine (0.04 mg/kg)18 to 0.1 mg/kg)6 IM

Telazol (1–4 mg/kg) IM (wild animals may be more sensitive)23

Chilla (Pseudalopex griseus)

Ketamine (2.5–3.1 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.05–0.06 mg/kg) IM1

Ketamine (9.3–17.7 mg/kg), xylazine (1.2–2.0 mg/kg) IM1

Telazol (1.6–8 mg/kg) IM1

Bushdog (Speothos venaticus)

Ketamine (5 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.05 mg/kg) IM7

Telazol (3 mg/kg), ketamine (3 mg/kg) IM7

Telazol (10 mg/kg) IM23

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

Ketamine (4 mg/kg), medetomidine (0.02 mg/kg), butorphanol (0.04 mg/kg) IM23

Ketamine (25–30 mg/kg), midazolam (0.6 mg/kg) IM23

Telazol (4–10 mg/kg) IM23 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Canidae

Chapter 46