Chapter 46 Camelids Are Not Ruminants

CLASSIFICATION AND EVOLUTION

Camelids are not ruminants taxonomically, physiologically, or behaviorally.7,8 Most importantly, from a veterinary standpoint, camelids and ruminants differ in susceptibility to infectious and parasitic diseases. The differences between camelids and ruminants should exclude camelids from being classified as ruminants. Nonetheless, camelids have been placed in various categories, such as “exotic animals,” “wild animals,” “other livestock species,” and “ruminants,” by state and federal regulators. Camelids have consistently been subjected to sudden, adverse regulations (some inappropriate) when an emerging disease of livestock appears on the scene.

When questioned about that action, the response was that ruminants are defined by an “encyclopedia” as animals that chew a cud, are cloven hoofed, and have three- or four-chambered stomachs. Regulators completely disregarded the scientific literature that clearly shows that foregut fermentation, complex multicompartmentalized stomachs, food regurgitation, and rechewing are not limited to “ruminants” but are found in species as diverse as kangaroos and nonhuman primates.13 In kangaroos, regurgitation and rechewing is referred to as merycism (Greek, “chewing the cud”). Foregut fermentation and multicompartmented stomachs are also seen in many species, including the hippopotamus, kangaroo, colobus monkey, and peccary.4

Modern paleontologic and taxonomic scientists clearly state that camelids belong in a separate suborder Tylopoda (Latin, “padded foot”) in the order Artiodactyla, which is distinct from the suborder Ruminantia* (Box 46-1).

Box 46-1 Classification of the Artiodactyla

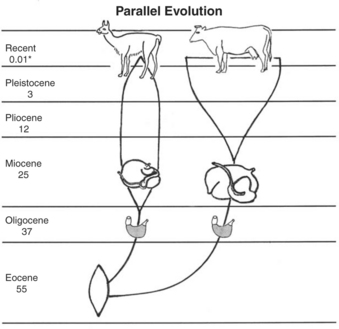

Camelid evolution began in North America 40 to 50 million years ago in the early Eocene epoch.6,7 Separation of the Tylopoda and Ruminantia occurred early in the evolutionary process, when the progenitors of both groups were small goat-sized animals with simple stomachs.33

Tylopods and ruminants continued to evolve by what is known as parallel evolution, which is the development of similarities in separate but related evolutionary lineages through the operation of similar selective factors acting on both lines6,7,33 (Figure 46-1).

Progenitors of the South American camelids (SACs) (guanaco, vicu-a, llama, and alpaca) migrated to South America at the beginning of the Pleistocene epoch (∼3 million years ago), when an open land connection between North and South America developed.6 Evolution continued in South America, where llama and alpaca were domesticated.9,10,35

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CAMELIDS AND RUMINANTS

Anatomic and physiologic differences between camelids and ruminants abound (Table 46-1).

Table 46-1 Differences Between Camelids and Ruminants

| South American Camelids | Ruminants | |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary pathways | Diverged 40 million years ago. | Diverged 40 million years ago. |

| Blood | ||

| Red blood cells | Elliptic and small (6.5 μm). | Round and large (10 μm). |

| Predominant white blood cell | Neutrophil. | Lymphocyte. |

| Leukocytes | Up to 22,000. | Up to 12,000. |

| Blood glucose levels | Higher than ruminants (73-121 mg/dL). | 18-65 mg/dL. |

| Integument | ||

| Horns or antlers | None. | Usually present in male. |

| Foot | Triangular-shaped toenails and fat pad covered by soft, flexible slipper. | Has hooves and sole. |

| Upper lip | Split and prehensile. | Not split. |

| Flank fold | None. | Pronounced. |

| Musculoskeletal system | ||

| Stance | Modified digitigrades. | Unguligrade ending in a hoof. |

| Second and third phalanges | Horizontal. | Almost vertical. |

| Foot | Not cloven. | Cloven. |

| Dewclaws | None. | Many have dewclaws. |

| Digestive system | ||

| Foregut fermenter, with regurgitation, rechewing, and reswallowing. | Same (parallel evolution). | |

| Stomach | Three compartments not homologous with rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum; all compartments have glandular epithelium; stomach motility from caudad to craniad; resistant to bloat. | Four compartments; susceptible to bloat. |

| Dental formula* | I 1/3, C 1/1, PM 1-2/1-2, M 3/3 × 2 = 28-32 | I 0/3, C 0/1, PM 3/3, M 3/3 × 2 =32 |

| Vicuña has incisors that continue to erupt. | ||

| Reproduction | ||

| Ovulation | Induced. | Spontaneous. |

| Estrous cycle | No. | Yes. |

| Follicular wave cycle | Yes. | No. |

| Copulation | In prone position. | In standing position. |

| Placenta | Diffuse and noninvasive. | Cotyledonary. |

| Epidermal membrane | Surrounding fetus. | None on fetus. |

| Cartilaginous projection on tip of penis | Yes. | No. |

| Ejaculation | Prolonged. | Short and intense. |

| Respiratory system | ||

| Soft palate | Elongated; primarily a nasal breather. | Short; nasal or oral breather. |

| Urinary system | ||

| Kidney | Smooth and elliptic. | Smooth or lobed. |

| Suburethral diverticulum | In female at external urethral orifice | None |

| Dorsal urethral recess | In male at junction of pelvic and penile urethra. | In some species. |

| Parasites | ||

| Lice | Unique biting and sucking lice. | Lice species different. |

| Coccidia | Eimeria species (coccidia) are different. | Unique species of coccidia. |

| Gastrointestinal nematodes | Share some with cattle, sheep, and goats. | Share with camelids. |

| Infectious diseases | ||

| Tuberculosis | Minimally susceptible. | Highly susceptible. |

| Bovine brucellosis | No known natural. | Highly susceptible. |

| Foot-and-mouth disease | Mild susceptibility. | Highly susceptible. |

| Rare clinical disease with other bovine and ovine viral diseases. | ||

| Behavior | ||

| Females do not lick their offspring | Females lick offspring. | |

| Females do not touch/lick aborted fetuses. | Females investigate dead fetuses. | |

| Females do not consume the placenta. | Females may consume the placenta. |

* I, incisors; C, canines; PM, premolars; M, molars.

Susceptibility to infectious and parasitic agents is of greater concern. The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has stated that camelids should be classified as ruminants because, “regardless of their taxonomic classification, camelids meet the definition of ruminants and are regulated as ruminants based on their susceptibility to ruminant diseases such as foot and mouth disease, tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis, M. tuberculosis, and M. avium), brucellosis, Johne’s disease, etc.”11

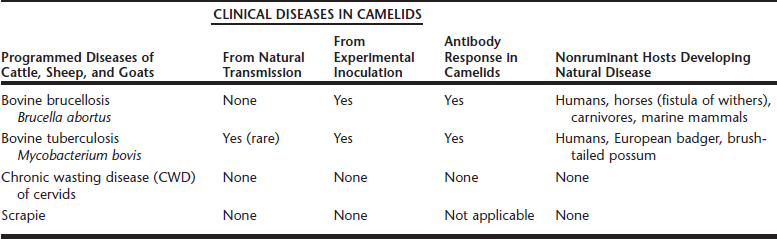

It is true that there are diseases that camelids, cattle, sheep, and goats all acquire, but a careful appraisal of Tables 46-2 through 46-9 should dispel the myth that “llamas and alpacas are susceptible to all cattle and sheep diseases.”34 In fact, they are quite resistant to many regulated ruminant diseases.

Table 46-2 Clinical Infectious Diseases of Camelids and Ruminants

| Camelids and Ruminants | Ruminants (Not Seen in Camelids) | Camelids (Not Seen in Ruminants) |

|---|---|---|

| Contagious ecthyma | Malignant catarrhal fever | Camelpox |

| Rabies (common to many mammals) | Bovine leukemia | Camel papillomatosis |

| Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD; occurs in many nonruminants) | Cowpox | Mycoplasma hemolama (Eperythrozoonosis) |

| Rinderpest (camels) | Pseudorabies | Lama adenoviruses, serotypes 1-6 |

| West Nile virus (WNV) encephalopathy (seen in many mammals and birds) | Bovine papillomatosis | |

| Fungal diseases (ringworm) (common to many mammals) | Ovine progressive pneumonia | |

| Tetanus and other clostridial diseases | Sheeppox or goatpox | |

| Bovine tuberculosis (seen in many nonruminant species) | Balanoposthitis | |

| Johne’s disease | Sheep or goat papillomatosis | |

| Necrobacillosis | Scrapie | |

| Streptococcosis (common to many nonruminant species) | Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) | |

| Staphylococcosis (common to many nonruminant species) | Chronic wasting disease (CWD) of cervids | |

| Caprine/ovine brucellosis | Bovine brucellosis | |

| Anaplasmosis |

Table 46-3 Infectious Disease Agents Producing Antibody Response, but Rare or No Clinical Disease in Camelids

| Agent | Disease |

|---|---|

| Bovine herpesvirus type 1 | Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis |

| Equine herpesvirus type 1 | Equine rhinopneumonitis |

| Retinal degeneration in SACs | |

| Bluetongue/epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus | Bluetongue, epizootic hemorrhagic disease of deer |

| Rift Valley fever virus (camels) | Rift Valley fever |

| Rotavirus | Enteritis (diarrhea) |

| Coronavirus | Enteritis (diarrhea) |

| Adenovirus | Enteritis (diarrhea) |

| Encephalomyocarditis virus | Encephalomyocarditis (EMC) |

| Brucella abortus | Bovine brucellosis |

| Borna disease virus | Viral encephalitis |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus | Vesicular stomatitis |

SACs, South American camelids.

Table 46-4 Programmed Diseases of Ruminants in United States Compared with Camelids and Other Species

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree