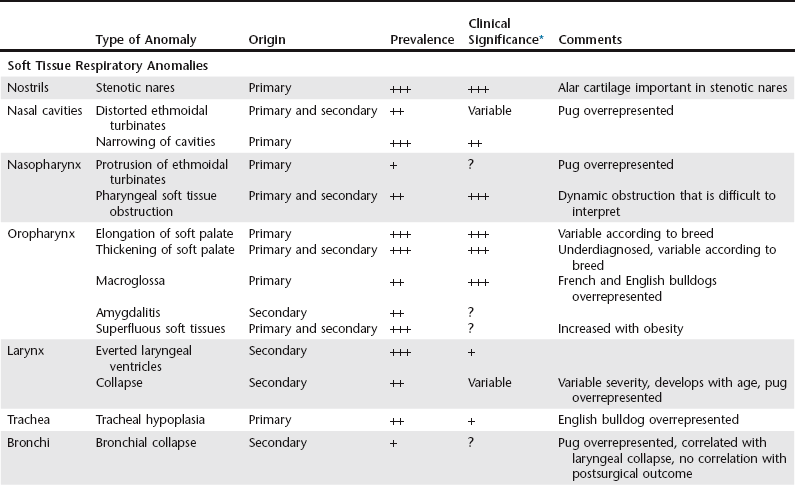

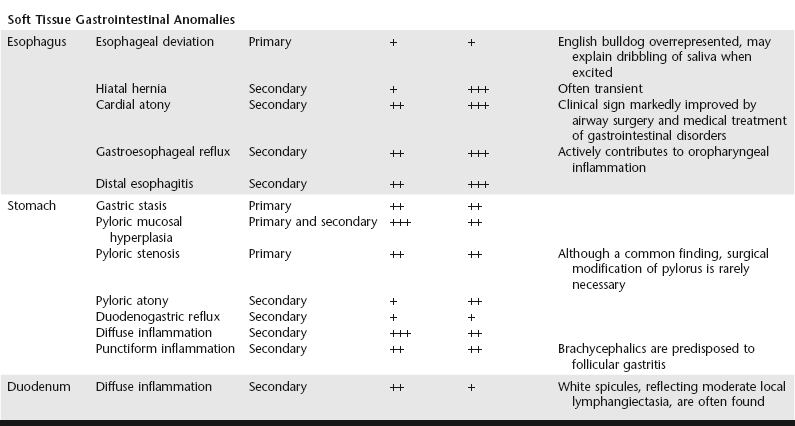

Chapter 156 In addition to stenotic nares and elongated soft palate, numerous other anomalies have been identified in these dogs. They may be congenital (primary) or acquired (secondary) (Table 156-1). The presence and severity of these anomalies vary from one dog to another and among the affected canine breeds. Although the clinical incidence of each entity may be expressed individually, each abnormality participates to a greater or lesser extent in an “engorgement” of the upper airways within a nondistensible cranial space. TABLE 156-1 Soft Tissue Anomalies of the Upper Respiratory and Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Associated with Brachycephalic Airway Obstruction Syndrome Prevalence: +, uncommon; ++, common; +++, frequent. Clinical significance: +, minimal; ++, moderate; +++, important; ?, uncertain. *Clinical significance based on clinical retrospective study or personal observations. The prevalence of gastrointestinal disorders is significant in dogs with upper airway obstruction and can be the principal reason for consultation. A study of 73 cases (Poncet et al, 2005) showed a high incidence of concurrent gastrointestinal disorders in brachycephalic dogs brought for treatment primarily of respiratory disorders. The clinical signs most commonly described by the owners include vomiting (of gastric juices or food, indicative of gastric retention), regurgitation (sometimes linked to exertion, but very commonly occurring when the dog becomes excited), eructation, ptyalism and repeated swallowing, and ingestion of grass or other form of pica. Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract enables visualization of gastrointestinal lesions and collection of gastric and duodenal biopsy samples; these are essential in dogs with gastrointestinal signs, because there is a poor correlation between the macroscopic and histologic appearance of the lesions. A prospective study of gastrointestinal lesions in 73 brachycephalic dogs (Poncet et al, 2005) revealed marked histologic lesions in 98% of cases in which biopsy samples were available. In this study a significant correlation was also established between the severity of the respiratory obstruction and the severity of gastrointestinal disorders.

Brachycephalic Airway Obstruction Syndrome

Clinical Signs

Diagnostic Approach

Brachycephalic Airway Obstruction Syndrome

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree