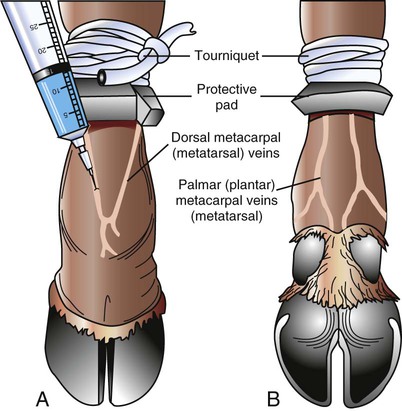

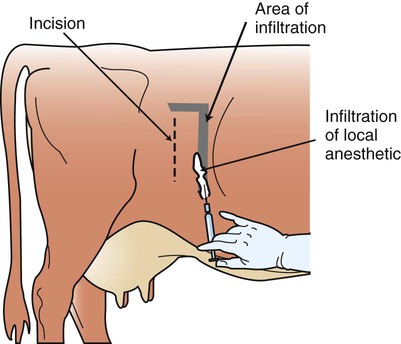

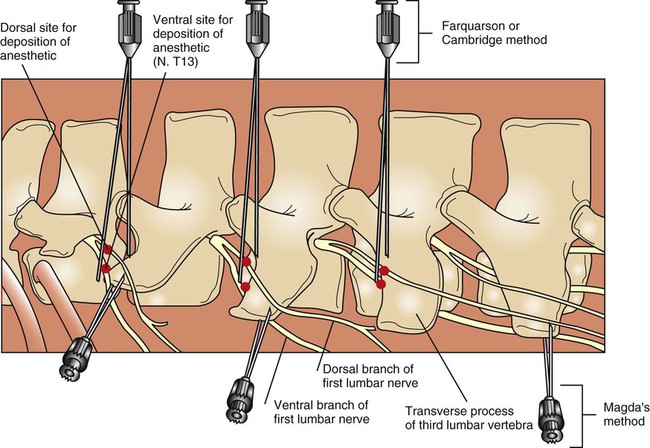

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to • Understand the basic differences between standing surgical procedures and general anesthesia procedures • Prepare a patient for surgery • Assist and/or perform induction and maintenance of anesthesia • Provide anesthetic monitoring • Manage the patient during recovery and immediate postoperative periods • Understand the basic risks and possible complications associated with anesthesia and surgery, and implement preventive measures when indicated As with equines, surgical procedures can be divided into two main categories: The overwhelming majority of ruminant surgeries are performed in the standing position, using a combination of sedation/tranquilization and local or regional anesthesia. Cattle generally seem to tolerate standing procedures better than do horses. Standing procedures are often used to repair traumatic injuries such as lacerations and punctures. Castration, cesarean section, correction of gastrointestinal (GI) tract abnormalities, enucleation, dehorning, and treatment of distal limb injuries are some of the more common standing surgical procedures. The indications and considerations for standing surgery in ruminants are identical to those in horses (see Chapter 8). The L block is a type of field block used to desensitize the flank for standing flank laparotomies. Local anesthetic is deposited in an inverted L configuration in the flank (Fig. 12-1). The anesthetic must be deposited in several layers (i.e., subcutaneous tissue and all muscular layers of abdominal wall). Large volumes of local anesthetic are required; often up to 100 ml of 2% solution is necessary in adult cattle. The anesthetic is deposited with an 18-gauge (ga) × This technique uses multiple specific nerve blocks to create a large region of flank anesthesia. Innervation of the flank arises from the spinal nerves of T13, L1, and L2 spinal segments. These nerves can be blocked near their exit from the vertebral column at a “paravertebral” location. The two main ways to approach these nerves are from (1) a dorsal approach near the intervertebral foramina (Cambridge, Farquharson, or proximal paravertebral method) or (2) a lateral approach near the tips of the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae (Magda, Cornell, or distal paravertebral method) (Fig. 12-3). Cattle require a 16- to 18-ga × 3- to 6-inch length needle for the proximal paravertebral (dorsal) approach. However, some clinicians prefer to first place a 14-ga × 1-inch needle as a trocar through the skin and muscle layers, then insert an 18-ga needle through the 14-ga needle to actually deliver the anesthetic. Up to 20 ml of anesthetic is necessary for each of the three injection sites in cattle. The cornual nerve block is used for desensitization of the horn and horn base for dehorning surgery. Cattle have a single nerve supply to each horn. The cornual nerve emerges from the orbit and ascends toward the base of the horn just below the temporal ridge of the frontal bone. Local anesthetic (≈ 3–5 ml in calves, 5–10 ml in adults) is deposited with an 18- to 20-ga × 1- to Any large superficial vein can be used, but generally the dorsal metacarpal (metatarsal) or palmar (plantar) metacarpal (metatarsal) veins are used (Fig. 12-5). The site should be clipped and prepped. Lidocaine without epinephrine (2%) or mepivacaine (2%) is injected intravenously, with the needle directed distally; the backpressure creates some resistance to injection. Up to 30 ml can be administered. After the needle is withdrawn, digital pressure should be placed over the injection site for longer than normal to prevent hematoma formation. The technique is similar to that described in horses. The procedure is performed through the dorsal aspect of the tail base, at the first intercoccygeal space (the sacrococcygeal space is another possibility but is more difficult to identify and less commonly used). To identify the first intercoccygeal space, manipulate the tail up and down while palpating the dorsal aspect of the tail base for the first obviously movable articulation (joint) caudal to the sacrum (Fig. 12-6). The area is clipped and sterilely prepped, and aseptic technique is used for the procedure. In general, blocking the skin and subcutaneous tissue is not necessary, but a small bleb of subcutaneous anesthetic can be placed with a 25-ga needle if desired. For placement of the epidural anesthetic, cattle require an 18-ga × The anesthetic generally takes effect in 10 to 20 minutes and lasts 1 to 2 hours on average. If prolonged anesthesia is necessary, a small-diameter epidural catheter (commercially available) or similar sterile medical tubing can be placed into the epidural space to provide continuous caudal epidural anesthesia. The catheter is placed and threaded cranially along the epidural space as in horses (Fig. 12-7). The catheter is placed and maintained aseptically. The end of the catheter is protected with an injection cap, and the exposed portion of the catheter should be secured to the skin. Small doses of lidocaine can be given every few hours as needed for pain or straining. A protective gauze bandage is advisable between uses. This technique spares the discomfort and tissue trauma from repeated standard epidurals. Disadvantages include kinking of the catheter and plugging of the tip with tissue or fibrin. Continuous caudal epidural anesthesia is also used successfully in equines. Other precautions include the following: • A cuffed endotracheal tube is essential to protect the trachea from aspiration. It should be inserted as soon as possible after anesthetic induction. Endotracheal intubation should be the priority of the anesthetic team at this time. Materials for intubation (oral speculum, appropriately sized endotracheal tube, sterile lubricant, laryngoscope, air syringe) should be assembled beforehand and readily available. • Stimulation of the pharynx/larynx, which occurs during intubation, may induce a gag reflex and cause regurgitation, especially in light planes of anesthesia. Intubation technique should be rapid and minimize stimulation of this area. The cuff should be inflated as soon as the tube is properly inserted. • Ruminants should never be rolled while they are under anesthesia unless a cuffed endotracheal tube is in place.

Bovine Surgical Procedures

Ruminant Surgery and Anesthesia

Standing Surgery

Control of Pain

L Block

– to 3-inch needle. Before beginning the surgical procedure, allow at least 10 to 15 minutes for the anesthetic to diffuse and take effect. The inverted L essentially forms a wall of anesthesia that protects the surgical field (Fig. 12-2). It is the simplest technique for desensitizing the flank and therefore is commonly used.

– to 3-inch needle. Before beginning the surgical procedure, allow at least 10 to 15 minutes for the anesthetic to diffuse and take effect. The inverted L essentially forms a wall of anesthesia that protects the surgical field (Fig. 12-2). It is the simplest technique for desensitizing the flank and therefore is commonly used.

Paravertebral Block

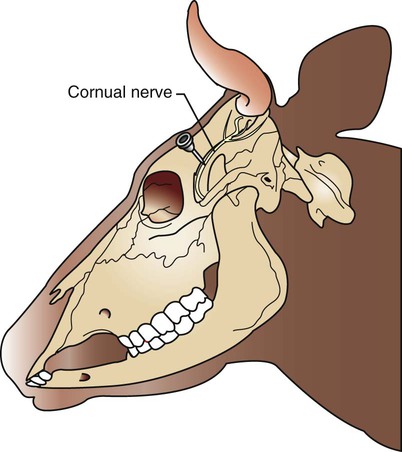

Cornual Nerve Block

-inch needle just ventral to the temporal ridge at a site approximately halfway between the horn base and the lateral canthus of the eye. The nerve is covered only by skin and a thin layer of muscle at this location; depth of needle penetration is 1 cm in calves to 2.5 cm in large adults (Fig. 12-4).

-inch needle just ventral to the temporal ridge at a site approximately halfway between the horn base and the lateral canthus of the eye. The nerve is covered only by skin and a thin layer of muscle at this location; depth of needle penetration is 1 cm in calves to 2.5 cm in large adults (Fig. 12-4).

Intravenous Regional Analgesia (Bier Block)

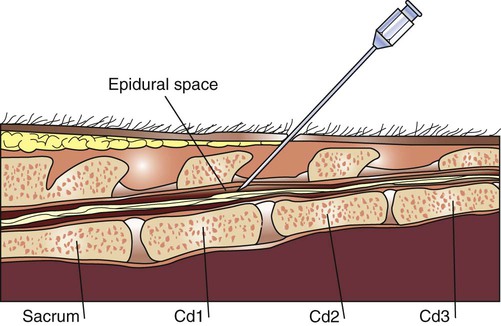

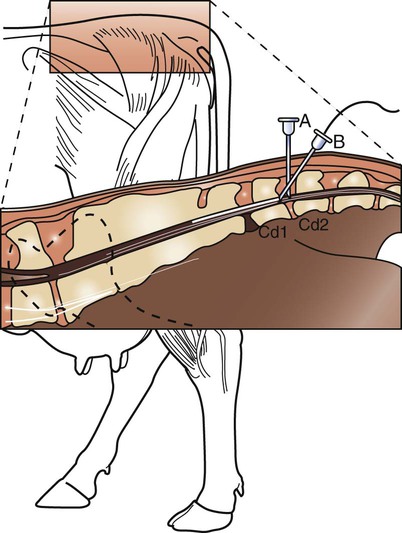

Caudal Epidural Analgesia

– to 3-inch needle. The needle enters on dorsal midline at a 45-degree angle, and anesthetic is deposited into the epidural space. Lidocaine 2% without epinephrine is most commonly used (1 ml/100 kg body weight, or ≈5–6 ml in adult cattle). Mepivacaine 2% also is suitable, and xylazine (Rompun) can be combined or used as the sole agent.

– to 3-inch needle. The needle enters on dorsal midline at a 45-degree angle, and anesthetic is deposited into the epidural space. Lidocaine 2% without epinephrine is most commonly used (1 ml/100 kg body weight, or ≈5–6 ml in adult cattle). Mepivacaine 2% also is suitable, and xylazine (Rompun) can be combined or used as the sole agent.

General Anesthesia

Anesthetic Risks for Ruminants

Regurgitation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

– to 3-inch needle is sufficient for cattle. From 10 to 20 ml of anesthetic is deposited at each of the three injection sites.

– to 3-inch needle is sufficient for cattle. From 10 to 20 ml of anesthetic is deposited at each of the three injection sites.