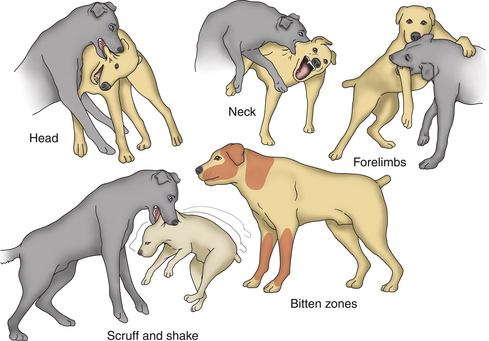

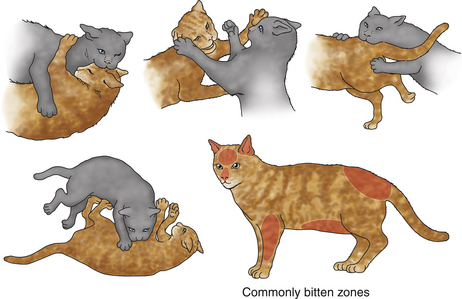

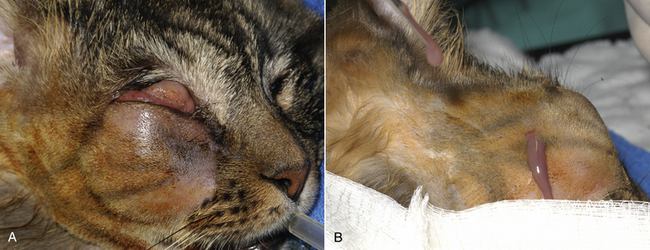

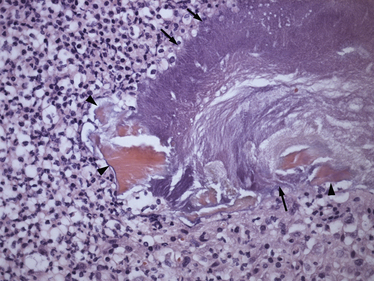

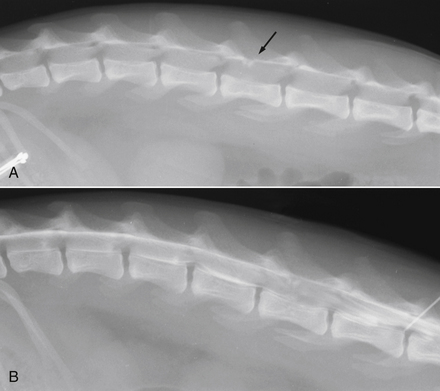

Chapter 57 Bite wounds are one of the most common reasons that dogs or cats are brought to veterinary hospitals for care. Despite this, there is surprisingly little information available on their epidemiology in comparison to the plethora of publications on animal bite wounds in people (see Public Health Aspects). Bite wounds often result in bacterial infection, but can also result in systemic viral infection (especially in the case of bitten cats), and less often, fungal or bloodborne protozoal infections such as babesiosis (Table 57-1). TABLE 57-1 Pathogens That Cause Local or Systemic Infections in Dogs and Cats as a Consequence of Bite or Scratch Wounds from the Same or Another Animal Species ∗The term ‘aerobe’ refers to facultative anaerobes and obligate aerobes. Bite wounds in dogs most often result from aggressive dog-dog interactions. The dog breeds affected depend on regional variation in dog breed popularity. Younger adult, male dogs and especially intact male dogs appear to be predisposed, but studies that compare affected dogs to a control (or “background”) population have not been reported.1–3 Bite wounds in dogs can also result from the bites of other domestic and wild animal species, but the epidemiology of infections that result from these wounds is not well described. Approximately 20% of dog-dog bite wounds become infected, as opposed to contaminated. The likelihood that a wound becomes infected increases with the time lag between the aggressive interaction and when veterinary attention is sought.2,3 Infection develops 8 to 24 hours after the bite occurs and is less likely to be develop if the wound is limited to the dermis.3 The distribution of bacterial species involved varies from one study to another and may be influenced by whether infected or only contaminated wounds were evaluated. The most common bacterial species isolated from dog-dog bite wounds are Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Enterococcus spp., Pasteurella spp., streptococci, and Escherichia coli.1–3 Staphylococcus aureus and Capnocytophaga canimorsus, which are important pathogens in humans that are bitten by dogs, are rarely isolated from bitten dogs,2,3 although the prevalence of C. canimorsus is probably underestimated because it is very difficult to grow in culture. In the author’s hospital, Pasteurella spp. accounted for 17% of 41 bacterial species cultured from 33 dog bite wounds, followed by a variety of staphylococci (some methicillin-resistant) (15%), E. coli (12%), Enterococcus spp. (7%), and Bacteroides spp. (7%). Other organisms were Peptostreptococcus spp., Clostridium spp., and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (each 5%); and Streptococcus viridans, Actinomyces spp., Acinetobacter spp., Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Myroides spp., Prevotella spp., Fusobacterium spp., Aeromonas spp., Mycobacterium smegmatis, and Mycoplasma spp. (one isolate each or 2%). Obligate anaerobes were isolated from 5 dogs (15%), and in all 5 of these dogs, multiple bacterial species were isolated. Most bite wounds in cats result from aggressive interactions with other cats, but nonfatal dog bite wounds can also occur. Occasionally, cats are bitten by a variety of other small wildlife species that vary geographically based on the local fauna present. In contrast to dogs, which often crush and tear tissues with their teeth, cats deliver deep puncture wounds that create an environment where obligate and facultative anaerobes flourish. Thus, anaerobic bacterial infections are more prevalent in cat bite abscesses than in dog bite wounds, and accordingly, polymicrobial infections are present more often in closed cat bite abscesses than in dog bite wounds. In a study of 36 closed cat bite abscesses, 168 bacterial strains were isolated, of which 72% were obligate anaerobes and 28% were facultative anaerobes.4 The most prevalent anaerobes isolated from cat bite abscesses include Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, and Fusobacterium. Pasteurella multocida, a commensal of the oral cavity of virtually all cats, is the most common facultative anaerobe present.4–6 Porphyromonas spp. appear to be particularly prevalent; in one study of 15 abscesses in Australian cats, they accounted for 92% to 99% of all the facultative and obligate anaerobes present.7 Less often Actinomyces, β-hemolytic streptococci, lactobacilli, and Propionibacterium spp. have been isolated. Among dogs, dog bite wounds consist of abrasions, lacerations, avulsions (i.e., skin flaps), crushing injuries, and deep puncture wounds (Figure 57-1). Abscesses can also develop. Dog bite wounds may also penetrate body cavities and cause pneumothorax or damage the esophagus, vertebral column, or gastrointestinal tract. Pyothorax or bacterial peritonitis can also occur. Most dogs have between 1 and 5 wounds. Rarely, more than 10 wounds are present.1–3 The majority of bite wounds occur cranial to the diaphragm, especially on the head and neck (Figure 57-2). The location of the bite wounds also depends on the size of the bitten dog; large-breed dogs are more likely to have wounds on the neck and face, but small-breed dogs often have wounds on their dorsum. Injury to underlying tissue is frequently dramatically more severe than is apparent on the surface. Classification systems have been used to describe the severity of dog-dog bite wounds based on the type of injury (laceration vs. puncture wound) and the presence or absence of dead space or abscessation.1–3 Abscessation is rarely associated with dog bite wounds as compared with cat bite wounds.3 The presence of pus, fever, erythema, subcutaneous emphysema, and/or a foul odor suggests that infection has occurred. Uncommonly, hematogenous spread of bacteria leads to signs of severe sepsis or septic shock (see Chapter 86). FIGURE 57-1 Dog bite wounds. A, Multiple puncture wounds, abrasions and lacerations to the abdomen of a 10-year-old female spayed mixed breed dog. A portion of the jejunum had perforated and had herniated into the subcutaneous tissue. The dog developed cardiac arrest after 2 days of aggressive treatment that included surgery and was euthanized. B, Five-year-old male neutered Pomeranian dog with a bite wound to the lateral cervical region from a pit-bull terrier dog that resulted in tissue avulsion. C, Inguinal region of a 6-year-old intact male German shepherd dog with severe bite wounds and tissue avulsion that resulted in extensive exposure of muscle and bone. The dog had been attacked by four other dogs. The dog survived with aggressive medical treatment and surgery that included amputation of the right pelvic limb. (Courtesy of the University of California, Davis Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care Service.) In cats, cat bite wounds may be difficult to identify on the surface, but infection can extend to penetrate bone, joints, tendon and muscle.5 Cat bite wounds are most often located on the forelimbs, lateral aspect of the face, and near the base of the tail (Figure 57-3).8 In contrast, scratches are often found on the bridge of the nose, pinna, and inguinal region. Cat bite abscesses are characterized by the presence of firm or fluctuant subcutaneous swellings or masses, with or without fever, lethargy, inappetence, and hyperesthesia. Some cats are brought to the veterinarian solely because of lethargy, and a careful physical examination is required before an abscess or cellulitis is detected. One or more scabs may be found on top of the abscess, or the overlying skin may lack hair and have a gray, necrotic appearance. If the abscess ruptures, cream-colored or red-brown purulent material may be identified on the haircoat, sometimes in association with a foul odor (Figure 57-4). Alternatively, the haircoat may be matted over the site. Lameness may be apparent if the limbs are involved, and especially if there is extension to the bone or a joint. Involvement of the thoracic cavity may be associated with fever, lethargy, tachypnea, and decreased lung sounds due to pyothorax (see Chapter 87). Bite wounds to the calvarium can result in neurologic signs such as circling, disorientation, head pressing, mental obtundation, delayed or absent placing reactions, tetraparesis, anisocoria, absent menace responses, and seizures.9 Penetration of the caudal vertebral column and spinal cord can lead to vertebral fractures, osteomyelitis, bacterial meningitis, and signs of pelvic limb paralysis (Figure 57-5). As in dogs, progression to severe sepsis or septic shock can occur, but most cat bite abscesses rupture and resolve spontaneously. FIGURE 57-3 Common anatomic distribution of cat-to-cat bite and fight wounds (“wound cat”). (Adapted from Malik R, Norris J, White J, et al. “Wound cat.” J Feline Med Surg 2006;8:135-140.) FIGURE 57-4 A, Six-year-old female spayed domestic shorthair cat with a cat bite abscess adjacent to the right eye that was associated with marked chemosis and periocular swelling. B, Purulent material discharged from the abscess when it was drained surgically. (Images courtesy University of California, Davis Veterinary Ophthalmology service.) FIGURE 57-5 Histopathology of the vertebral column of a young adult, male domestic shorthair that was found with a bite wound to the base of the tail that drained purulent material and pelvic limb paralysis with absent deep pain sensation. Multiple fractures of caudal vertebrae 4 and 5 were present in association with suppurative osteomyelitis (arrowheads), cellulitis, ascending meningitis, and masses of intralesional bacteria (arrows). Multiple anaerobes were cultured from the lesion. H&E stain. Cats with dog bite wounds often have life-threatening injuries. Fractures, severe hemorrhage, and hypovolemic shock can dominate the clinical picture. Penetrating injury of cervical structures, the thorax, abdominal organs, brain, or spinal cord can occur (Figure 57-6). Death most often results from trauma rather than infection, but occasionally deep-seated infections or bacteremia develops if the cat survives the initial traumatic episode. FIGURE 57-6 A, Lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine of a 3-year-old female Siamese cat with a dog bite wound to the lumbar spine. The cat was unable to stand and had absent placing reactions in the pelvic limbs. Patellar reflexes were also absent. Two osseous densities are superimposed at the level of the dorsal spinal canal at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra (L4) (arrow). The dorsoventral view showed deviation of the spinous process of L4 (not shown). CSF analysis revealed mild suppurative inflammation. B, Myelogram. A spinal needle is inserted at L5-6 for injection of contrast agent. Spinal cord widening with associated thinning of the contrast column circumferentially is identified over the body of L4. Dorsal deviation and splitting of the ventral contrast column is present over L2-3 as a result of disc protrusion in this region. A decompressive hemilaminectomy over L4 to L6 was performed and a bone fragment was removed; the cat ultimately recovered. A diagnosis of bite wound infections is based on history of a fight or bite and physical examination findings that suggest that infection has developed. Cytologic examination of a wound may also assist in diagnosis of infection. The veterinarian should record whether the wound was provoked or unprovoked and note time and location that the wound occurred and the biting animal species involved. Depending on the extent and location of bite wounds, radiographs of the affected region should be considered to assess for underlying damage to bone or body cavities. All cats with cat fight wounds should be tested for FeLV and FIV infection, and the test should be repeated 2 months later because transmission may have occurred at the time of the fight wound (see Chapters 21 and 22). Laboratory abnormalities in cats or dogs with wound infections are variable and depend on the degree of tissue trauma, the underlying organs involved (if any), and the severity and type of infection. The CBC may show nonregenerative or regenerative anemia, neutrophilia with bandemia, toxic neutrophils, monocytosis, and lymphopenia or lymphocytosis. Animals with severe sepsis or septic shock may be thrombocytopenic. Findings on the chemistry panel include hypoalbuminemia and evidence of muscle damage (increased activities of CK, AST, and sometimes mild increases in serum ALT activity). Increased muscle enzyme activities may be a clue to an underlying cat bite wound in cats with fever of unknown origin. Prolongations of the PT and/or APTT may be present in animals with septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Radiographs of the thorax in dogs or cats with bite wounds may show fractured ribs, pneumothorax, evidence of pulmonary contusions, mediastinal emphysema, diaphragmatic herniation, or pleural effusion due to hemothorax or pyothorax. Abdominal radiographs may show a lack of serosal detail due to hemoabdomen or bacterial peritonitis. Radiographs of the axial or appendicular skeleton may reveal fractures or tooth foreign bodies. In more chronic bite wound infections, evidence of osteomyelitis or septic arthritis may be present, with soft tissue swelling and bony lysis (see also Chapter 85). Ultrasound of soft tissues can be useful to assess the extent of bite wound infections. Abdominal ultrasound is indicated for animals with bite wounds to the abdomen to assess for evidence of peritonitis or trauma to abdominal organs. Findings in dogs or cats with peritonitis include a hyperechoic mesentery with an irregular outline and free peritoneal fluid, which is typically echogenic (see Chapter 88). Findings on MRI in cats with brain abscesses secondary to cat bite wounds include space-occupying lesions with well-defined margins that are hyperintense on T2-weighted images, and hypointense T1-weighted images.9 Marked ring enhancement is usually present. Evidence of brain herniation may be detected.9

Bite and Scratch Wound Infections

Etiology and Epidemiology

Organism Class

Dogs

Cats

Viruses

Rabies

Rabies

FeLV

FIV

Mycoplasmas

Hemotropic mycoplasmas?

Nonhemotropic Mycoplasma spp.

Hemotropic mycoplasmas?

Gram-negative aerobes∗

Pasteurella spp.

Escherichia coli

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Acinetobacter spp.

Proteus spp.

Enterobacter spp.

Serratia marcescens

Aeromonas spp.

Capnocytophaga canimorsus

Pasteurella spp.

Escherichia coli

Gram-positive aerobes∗

Staphylococcus spp., especially S. pseudintermedius

Streptococcus spp.

Enterococcus spp.

Actinomyces spp.

Corynebacterium spp.

Streptococcus spp.

Enterococcus spp.

Actinomyces spp.

Nocardia spp.

Lactobacillus spp.

Corynebacterium spp.

Anaerobes

Bacteroides spp.

Clostridium spp.

Porphyromonas spp.

Fusobacterium spp.

Peptostreptococcus spp.

Propionibacterium spp.

Prevotella spp.

Eubacterium spp.

Bacteroides spp.

Prevotella spp.

Porphyromonas spp.

Fusobacterium spp.

Clostridium spp.

Propionibacterium spp.

Mycobacteria

Tuberculous mycobacteria (e.g., M. bovis in the United Kingdom)

Rapidly growing mycobacteria

Tuberculous mycobacteria (e.g., M. microti in the United Kingdom)

Rapidly growing mycobacteria (e.g., M. fortuitum)

Lepromatous mycobacteria (e.g., M. lepraemurium)

Fungi

Sporothrix schenckii

Sporothrix schenckii

Opportunistic molds (e.g., Paecilomyces spp.), dematiaceous molds

Protozoa

Babesia gibsoni

Babesia conradae?

None known

Dogs

Cats

Clinical Features

Cats

Diagnosis

Laboratory Abnormalities

Diagnostic Imaging

Sonographic Findings

Advanced Imaging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Bite and Scratch Wound Infections

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue