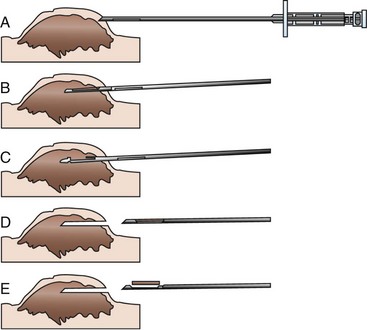

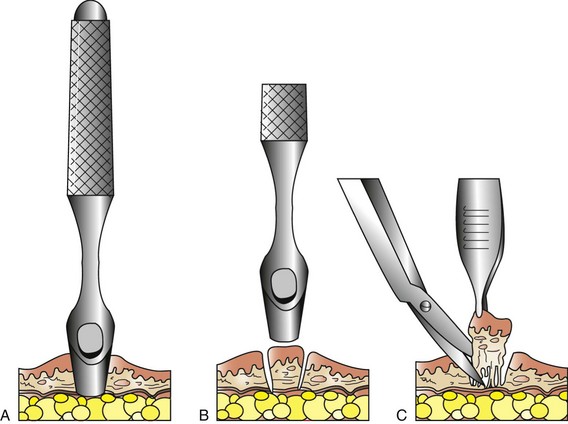

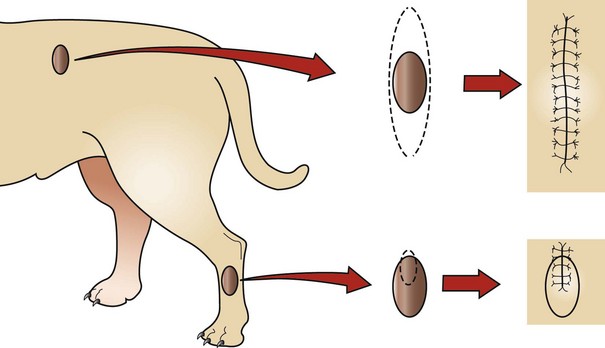

Chapter 21 Biopsies are performed to determine the presence or extent of disease present in sampled tissue. Samples may be required for histopathologic diagnosis, molecular evaluation, immunohistochemical testing, phenotyping, and polymerase chain reaction testing for DNA analysis.1,7,17 Presurgical planning is required to ensure that the appropriate quality and quantity of tissue is harvested to maximize the chance of obtaining a correct diagnosis. An incorrect diagnosis will result in exponential expansion of improper diagnostic testing and treatment of the patient. If more tissue is removed subsequent to the procurement of a sample for biopsy, repeated analysis of the tissue is always prudent. Regardless, if tissue is deemed important enough to be removed from a patient, then it is important to have that tissue histopathologically examined. Definitive indications for surgical biopsy and knowledge of the primary process will affect the type of treatment (surgical, medical, chemotherapeutic, radiation), the extent of treatment (marginal, wide, or radical excision), the ability to plan for surgery (areas requiring reconstructive surgery), and the prognosis associated with the condition (which may affect owner decisions as to therapy).7 Rare contraindications to biopsy collection are known and include conditions in which the type of treatment or the extent of surgery cannot be altered and those in which the risk associated with biopsy is as great as the risk of definitive excision.1,7,11 The differential diagnoses must be considered in such cases and usually are well known before proceeding. For example, testicular mass lesions have a limited differential list and a limited treatment plan for excision, so prior biopsy is not usually performed. Likewise, spinal cord masses have a limited differential diagnosis list, and surgery cannot be altered for therapy. The benefits of needle-core biopsies include the ability to rapidly and easily obtain tissue samples in awake or sedated patients, which allows outpatient sampling. Deeper sampling may require general anesthesia, and needle biopsy specimens can be taken during endoscopic or open procedures. Agreement with incisional biopsy samples is high—96% for superficial masses in the skin or subcutis.5,17 Disadvantages include sample size and quality. Depending on the structure sampled, crush artifact, inaccurate tissue collection (e.g., muscle rather than kidney), and diminished quality of the sample for diagnosis have been associated with needle-core biopsies of organs.7,16 The main risk associated with needle-core biopsies is hemorrhage. The needle must be directed deep into the area to be sampled—as far as 1.5 cm; this may result in vascular trauma and hemorrhage.15 It is also important to note that seeding of cells involved in the disease condition will occur along the path of the needle through surrounding tissue before entry into the lesion.1,7 Spread of these cells should be considered, and a direct path through the least amount of normal tissue should be made. The patient may be awake, sedated, or placed under general anesthesia for the sampling procedure, depending on accessibility and the anatomic location sampled. Additional local anesthetic at the site of skin puncture is recommended. The skin over the site through which the needle will travel to the intended target should be adequately clipped of hair and aseptically prepared for surgery. A small stab incision is made in the skin, and the needle is introduced in its closed position (Figure 21-1). Palpable mass lesions should be manually stabilized with the clinician’s nondominant hand, and the needle introduced through surrounding tissue and into the mass. Deep organs are evaluated for areas of lesser blood flow, and the needle is guided into the tissue visually under ultrasound or laparoscopy. Laparoscopic guidance may also include use of a retractor or palpation probe to stabilize the tissue to be sampled (e.g., kidney). Open abdominal or thoracic needle biopsy samples can be taken by insertion of the needle directly into the structure to be sampled. The instrument consists of an inner, sampling cannula/chamber and an outer cutting sheath. An automated instrument is simply fired (spring-loaded instruments require preloading) into the tissue.15 Manual needle-core instruments require insertion of the sampling chamber into the structure and stabilization of the sampling chamber, while the outer cutting sheath is rapidly advanced for sampling. Manual firing may be done with one or two hands: The nondominant hand may be used to stabilize the sampling chamber, while the dominant hand rapidly advances the outer cutting sheath; alternatively, the dominant hand may be used for stabilization and cutting. If the one-handed technique is used, the thumb and middle/index fingers stabilize the cutting chamber, and the index finger advances the outer cutting sheath. Some clinicians use a one-handed technique, in which the palm and fingers stabilize the inner sampling chamber and advance the outer cutting sheath with the thumb. Punch biopsies are commonly performed for skin lesions and provide a cylindrical core of tissue. Their use has been extended by incising the skin to sample deeper mass lesions, or they may be used in open procedures to biopsy central areas of the liver. The skin should be appropriately prepared for the procedure; it is important to note that punch biopsies for skin disease may not involve clipping and usual preparation to avoid alteration of the skin surface on histopathologic examination. The punch is gently rotated clockwise and counterclockwise while advanced into the tissue to be sampled (Figure 21-2). Upon removal of the punch, Metzenbaum scissors are inserted into the base of the incision to transect the sample from the underlying tissue. If used for hepatic biopsy, hepatic parenchymal hemorrhage is controlled with hemostatic foam (Gelfoam, Pfizer, New York) or cellulose (Surgicel, Ethicon, Inc., Cincinnati). Superficial lesions of the skin are sutured closed with an appropriate number of interrupted skin sutures. Biopsy of deeper lesions involves routine closure of the biopsy site with interrupted simple or horizontal mattress sutures followed by routine closure of overlying tissues. Incisional biopsies usually consist of removing a wedge of tissue from a target site. Incisional biopsy is commonly utilized for mass lesions, for lymph node biopsy, and for gastrointestinal tract sampling, and may be used to sample the kidney. The resultant sample is better than that obtained with fine needle aspiration cytology and is usually larger than that obtained with needle-core biopsies.3,16,19 Incisional biopsies are preferred to punch or needle-core biopsies for superficial, ulcerated, and necrotic mass lesions, as larger samples can be obtained, increasing the chance of obtaining a diagnostic sample.1,7 Because tumors are poorly innervated, incisional biopsies of superficial mass lesions may be done with the patient awake or under sedation, usually with concurrent use of local anesthetic. Intact skin over the mass should be adequately anesthetized following clipping of hair and appropriate preparation of the skin. Ulcerated masses may not require local anesthetic.7 Planning of wedge biopsy for mass lesions is important. The initial incision should be only as large as is necessary to obtain an adequate sample size for diagnosis and should be oriented to allow future excisional surgery and adjuvant therapy, the most important of which is radiation therapy7 (Figure 21-3). Consider the possible differential diagnoses and whether wide excision or radiation therapy may be necessary, and orient the incision appropriately with lines of tension and beam targeting to avoid sensitive organs or structures. Sometimes the two are oppositely arranged, and careful thought is needed before sampling.

Biopsy General Principles

Biopsy Methods

Punch Biopsy

Incisional Biopsy

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Biopsy General Principles

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue