Chapter 3 Beagle dog

Introduction

The majority of dogs used in toxicity studies are young beagles (generally less than one year old at the start of study), and therefore a limited range of background findings is recognized compared to the ageing population of dogs generally seen in veterinary pathology diagnostic facilities. The most common observations are minimal inflammatory-cell foci, usually predominantly mononuclear cells, of unknown etiology. Inflammatory-cell foci are seen in many organs but are particularly common in the liver (Foster 2005), lung, salivary glands and tongue. Other common findings include granular brown pigment in the spleen (usually hemosiderin) and liver (usually lipofuscin) and agonal congestion of the vasculature, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract (Haggerty et al 2007). Other background and incidental findings are seen with varying incidence depending on the strain, supplier and test facility, and are illustrated below.

Cardiovascular system

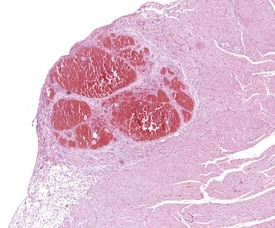

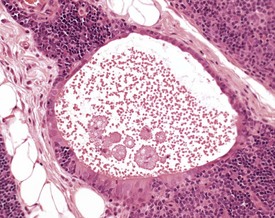

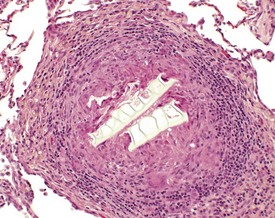

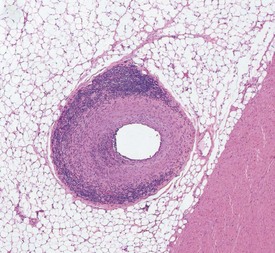

Young dogs of all breeds – including beagles – may show spontaneous lesions including focal telangiectasia (hematocysts) of the heart valve (Fig. 3.1) and endocardiosis (Takeda et al 1991). Hematocysts are seen macroscopically as dark red or black cysts on valve cusps. The incidence of endocardiosis increases with age, with a frequency of 11–25% reported in lifetime studies of beagles (Van Fleet 2001). Arteritis is seen sporadically, reportedly in 5–10% of young beagles (Grant Maxie & Robinson 2007), and occurs more commonly in males, affecting either single or multiple vessels, most commonly in the epididymides, thymus, and the coronary arteries of the heart (Fig. 3.2) (Son 2004). In the majority of cases in young dogs the lesions are idiopathic (Hartman 1987) and occur in the absence of any clinical signs, but they can also occur as part of the ‘beagle pain syndrome’. Distinguishing spontaneous lesions from those induced by drugs can be difficult, and pathologists may need to use a weight-of-evidence approach based on the incidence, distribution of lesions, morphological appearance, and associated pathology (Clemo et al 2003) to reach a diagnosis.

FIGURE 3.2 Arteritis and periarteritis of extramural coronary artery. ×200.

Image courtesy of E McInnes.

Mineralization of the root of the aorta (Glaister 1986, Kelly et al 1982) (Fig. 3.3) and other vessels is occasionally seen in young dogs, although the incidence increases with age (Schwarz et al 2002). In beagles, this lesion can occur in animals with normal serum calcium and phosphorus levels, in the absence of any other pathology, and may only be visible microscopically.

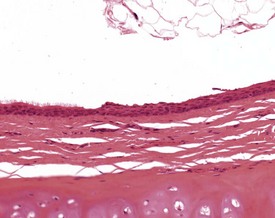

Intimal thickening as the result of musculoelastic proliferation of intramural vessels in the myocardium (Grant Maxie & Robinson 2007) and pulmonary vessels (Fig. 3.4) can be found in normotensive laboratory dogs. The change needs to be distinguished from oblique planes of section through blood vessel walls, particularly where there is the possibility that there are drug-induced changes in vascular tone or blood pressure. There is little literature on the spontaneous incidence of these changes (Detweiler et al 1961).

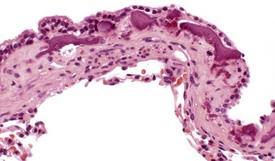

Villous mesothelial proliferations are occasionally seen attached to the epicardium and pleura (Mesfin 1990) (Fig. 3.5), possibly resulting from local friction or other stimulation. These projections consist of an extracellular matrix core surrounding capillaries covered by a cuboidal mesothelial lining.

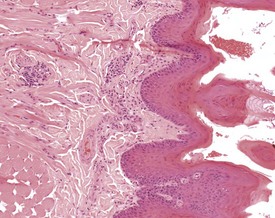

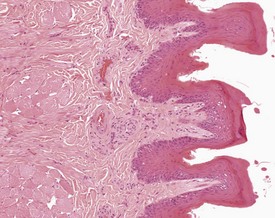

Hemolymphoreticular system

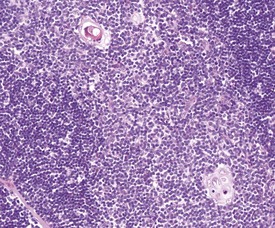

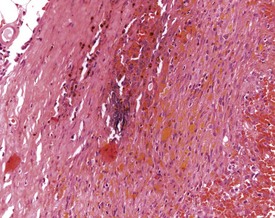

Few lesions are recorded in the lymphoid tissues of young beagles. Thymic cysts or epithelial remnants from the branchial pouches (Fig. 3.6) are commonly seen in the medulla (Newman 1971), as in other species, and may increase in prominence with involution. Prominent Hassall’s corpuscles may also be seen in the thymic medulla (Snyder et al 1993) and are composed of concentric layers of keratin (Fig. 3.7). In the spleen of young dogs haemosiderotic foci or plaques may not be obvious macroscopically, but may be seen microscopically, usually associated with connective tissue trabeculae or in connective tissue around the hilar vessels (Fig. 3.8). In older animals these are recognized macroscopically as yellow or grey encrustations or nodules along the capsular borders, sometimes referred to as Gandy–Gamna bodies.

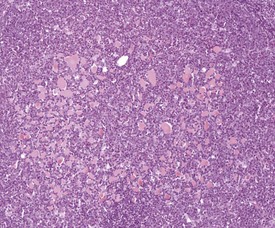

Accessory spleens may be present in the omentum or attached to the surface of the spleen. They appear as brown nodules, usually less than 2mm in diameter (Kelly et al 1982, Patnaik 1985), and they have their own independent blood supply. Hyalinized material may occasionally be seen in the follicles of lymph nodes and spleen (Fig. 3.9). In some cases this may be amyloid deposition but may alternatively be accumulations of immunoglobulin.

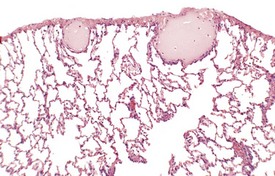

Respiratory system

Normal histological variations occur throughout the respiratory tract and include foci of squamous epithelium (Fig. 3.10) in the trachea. Pulmonary mineralization can occur in two forms: either associated with the alveolar interstitium, when it tends to be diffuse or multifocal, or as focal osteophyte formation (Fig. 3.11). Diffuse pulmonary mineralization is reported in dogs with uraemia and Cushing’s syndrome (Berry et al 2005) but can also be an idiopathic finding, and subepithelial mineralization of peribronchiolar smooth muscle (Fig. 3.12) can be seen as a spontaneous finding in control beagles (D J Lewis, personal communication).

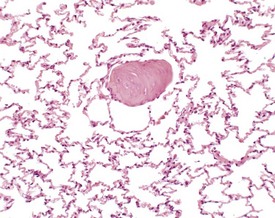

FIGURE 3.11 Focal osseous metaplasia or osteophyte formation in lung parenchyma.

Image courtesy of DJ Lewis. ×200.

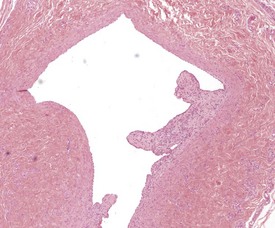

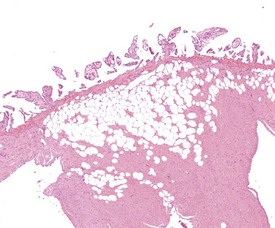

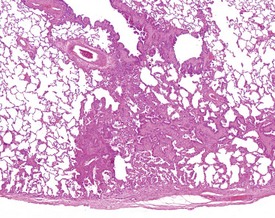

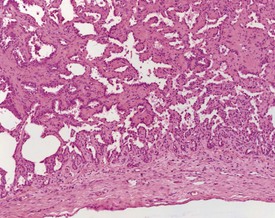

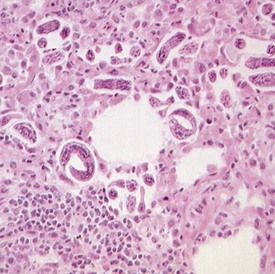

Fibrosing alveolitis, also known as segmental fibrosis, may be seen macroscopically as pale, white, focal thickenings of the pleural surface, often at the edges of the lung lobes. Microscopically (Figs 3.13, 3.14) these lesions are wedge-shaped areas of alveolar fibrosis extending into the lung parenchyma from the pleura, with associated epithelial hyperplasia and occasional small numbers of chronic inflammatory cells (Glaister 1986, Hahn & Dagle 2001). These lesions are well recognized in beagle tissues but do seem not to be reported in the veterinary literature. There is some confusion about the cause of these lesions. Almost invariably no etiological agent is seen in the sections, although they may represent damage caused by previously migrating parasites such as Filaroides and Toxocara species. Filaroides hirthi lung infestations have been reported in beagle colonies with demonstrable parasites (Bahnemann & Bauer 1994, Hottendorf & Hirth 1974), but the current incidence is unknown in laboratory colonies. In active Filaroides infections macroscopic tan, grey or green nodules may be seen on the pleural surface associated microscopically with granulomas with eosinophils with or without cross sections of worms (Fig. 3.15). These granulomas should be distinguished from those which occur secondarily to the inhalation of foreign material or due to emboli of keratin from intravenous injection sites (Fig. 3.16) (Hottendorf & Hirth 1974). Dilated pleural lymphatics are occasionally seen and may be artefactual, related to changes in pulmonary pressure due to clamping or infusion with fixative (Fig. 3.17) (Colby et al 2007).

FIGURE 3.15 Cross sections of Filaroides larvae with associated eosinophilic and granulomatous reaction.

Image courtesy of A Bradley. ×200.

Gastrointestinal system

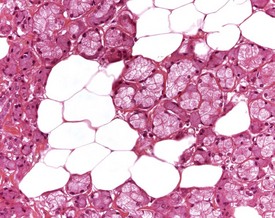

Subepithelial inflammatory deposits are common in the dog tongue, and occasional granulomas and focal ulcers may be associated with particles of foreign material, for example sawdust bedding (Fig. 3.18). These infiltrates need to be distinguished from the cellular arteriovenous anastomoses (Fig. 3.19) which lie below the epithelium (Pritchard & Daniel 1953). Adipocyte infiltration of the salivary glands may be seen incidentally without clinical correlation or inflammation (Fig. 3.20), although it is reported to cause palpable glandular enlargement in older animals (Bindseil & Madsen 1997, Brown et al 1997).

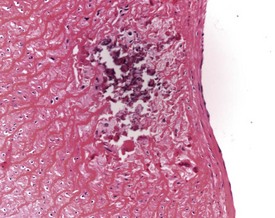

Mineralization of the gastric mucosa (Fig. 3.21) is observed with varying incidence (5–10%) in beagles with no underlying pathological lesions (Glaister 1986, Majeed 1985). In some dogs occasional small microscopic foci of mineralization may be observed, but in some animals the deposits may be considerably more extensive leading to a gritty feel when the mucosa is handled. It was previously suggested (Majeed 1985) that this may relate to dietary imbalances of calcium and phosphorus, but mineralization is now found in dogs with normal serum calcium or phosphate levels fed on balanced modern diets, and so the underlying cause remains unknown.

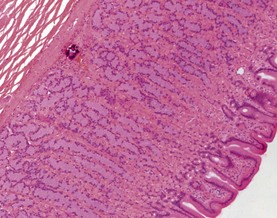

FIGURE 3.21 Focal mineralization in gastric mucosa. Note absence of inflammatory response.

Image courtesy of C Lopez. ×100.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree