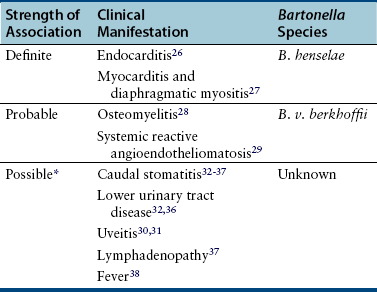

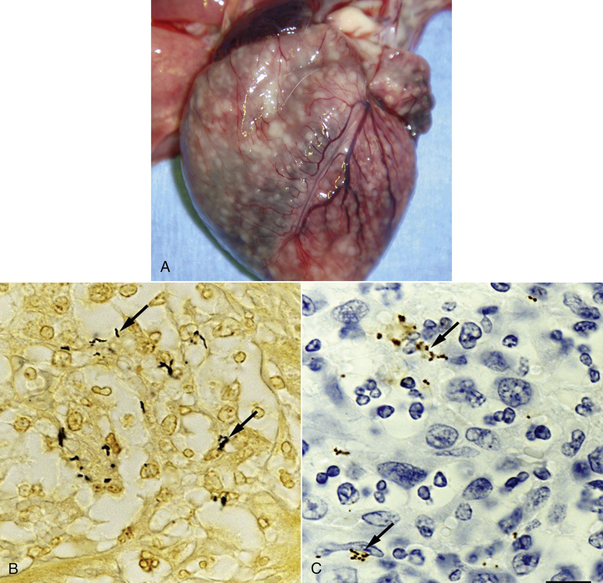

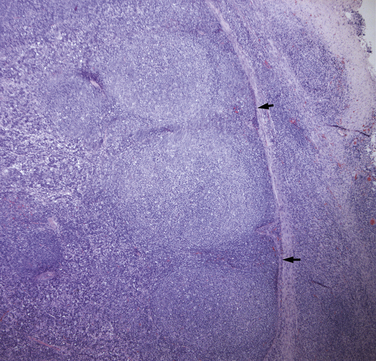

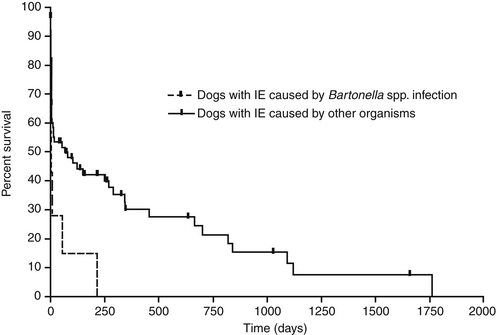

Chapter 52 Bartonella spp. are fastidious, intraerythrocytic gram-negative bacteria that infect a wide range of domestic and wild mammalian host species. Different Bartonella species have adapted to specific mammalian reservoir hosts and can infect and occasionally cause disease in alternative, incidental hosts. More than 10 species of Bartonella infect cats or dogs worldwide (Tables 52-1 and 52-2). Bartonella infections are important because cats are the principal reservoir host for Bartonella henselae, the main cause of cat scratch disease (CSD) in humans, and subclinical bacteremia in cats is widespread (8% to 56% of healthy cats worldwide).3 TABLE 52-1 Species of Bartonella Known to Infect Cats TABLE 52-2 Species of Bartonella Known to Infect Dogs Cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) play a major role in the transmission of feline Bartonella infections. The presence of cat fleas is essential for maintenance of the infection within the cat population.4 B. henselae can multiply in the digestive system of the flea and survive several days in flea feces.5 The main source of infection appears to be flea feces that are inoculated by contaminated cat claws.6 There is some evidence that Bartonella is present in the saliva of cats, but shedding of B. henselae in cat saliva has not been clearly documented. Other potential vectors, such as Pulex flea species, ticks, lice, and biting flies, also harbor Bartonella DNA, and experimental transmission of Bartonella birtlesii has been accomplished with Ixodes ricinus ticks.7 There is epidemiologic evidence that ticks may transmit Bartonella to dogs. Because Bartonella infections are often subclinical in dogs and cats, the full extent to which Bartonella spp. cause disease in naturally infected dogs and cats remains unclear. Bartonella spp. have been widely studied for their role in a number of idiopathic inflammatory disorders of cats, including uveitis, lymphadenopathy, caudal stomatitis, and rhinitis, without definitive evidence of disease causation. Without doubt, they are important causes of endocarditis in dogs and occasionally cause endocarditis and myocarditis in cats (Table 52-3 and Box 52-1). TABLE 52-3 Examples of Clinical Manifestations That May, in Some Circumstances, Be Associated with Bartonella Infection in Naturally Infected Cats ∗Results of experimental studies are conflicting or there is insufficient evidence to prove an association with disease. The most common Bartonella species isolated from cats is B. henselae. Less commonly, cats are infected with Bartonella clarridgeiae or Bartonella koehlerae, which also have been linked to human disease.5,8 Young cats (≤1 year) are more likely than older cats to be bacteremic, and stray or feral cats are more likely to be bacteremic than pet cats.5,9,10 Older cats are more likely to be seropositive than young cats, which likely reflects the increased chance of exposure over time. The prevalence of Bartonella bacteremia in cats is also highest in warm, humid climates (e.g., 68% in the Philippines), whereas it is low in colder climates (e.g., 0% in Norway).5 At least two genotypes of B. henselae infect cats, type Houston-1 (type I) and type Marseille (type II). B. henselae type Marseille predominates among cats in the western United States, western continental Europe, the United Kingdom, and Australia; type Houston-1 is dominant in Asia (Japan and the Philippines).5 However, within a given country, the prevalence of these types varies among cat populations, and type Houston-1 is more often isolated from humans with bartonellosis, even when type Marseille is more prevalent in the cat population. Some molecular typing methods reveal an even broader genetic diversity among feline strains, and most of the strains that infect humans cluster in a limited number of groups. Dogs are most commonly infected with Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii or B. henselae. Domestic and wild dogs are thought to be the natural reservoir for B. v. berkhoffii, because B. v. berkhoffii establishes prolonged bacteremia in dogs. In California, 35% of coyotes (Canis latrans) tested were seropositive, and 28% of coyotes from a highly endemic region were bacteremic.5 Other Bartonella species have also been detected in dogs (see Table 52-2). Novel species also have been identified in dogs from Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the Mediterranean.11–13 Because it is often difficult to culture Bartonella from domestic dog blood, prevalence studies in dogs are usually based on antibody detection. Unfortunately, this correlates poorly with bacteremia. In addition, serologic cross-reactivity occurs among Bartonella species so seroprevalence studies cannot be Bartonella species-specific. The prevalence of antibodies to B. v. berkhoffii in dogs is highest in tropical or subtropical regions. For example, seroprevalences as high as 47% were detected in stray dogs from Morocco.14 In the southeastern United States, the prevalence of B. henselae antibodies in healthy dogs was 10%; a higher prevalence (27%) was found in sick dogs.15 Risk factors identified in dogs in the southeastern United States were tick exposure, residence in a rural environment, roaming, and outdoor exposure.16 The prevalence of B. henselae antibodies in sick dogs from the western United States is less than 2%.17 After infection, Bartonella replicates in erythrocytes and can also infect endothelial cells and bone marrow progenitor cells.18 It then establishes chronic, often subclinical bacteremia, which can last for weeks, months, or even more than a year and may be a specific adaptation to a mode of transmission by blood-sucking arthropods.19 Infection of endothelial cells may be more likely to occur in incidental hosts and appears to be necessary for the development of disorders such as vasculoproliferative disease and endocarditis. Bartonella is thought to cause vasculoproliferative disease via cytokine-induced stimulation of endothelial cell proliferation and inhibition of endothelial cell apoptosis. Virulence factors characterized in Bartonella species include adhesins, heme acquisition mechanisms, type IV secretion systems, and a low-potency lipopolysaccharide, among others.20 Host immunocompromise, such as due to genetic susceptibility (e.g., breed-related immunodeficiency syndromes), poor nutrition, overcrowding, co-infections with other pathogens, immunosuppressive drug treatment, or defects in normal host barriers (such as congenital valvular disease in dogs with endocarditis), may also influence whether disease ultimately develops in infected dogs and cats. Experimental infections of specific pathogen free cats with Bartonella have shed light on disease processes that can follow infection of cats with Bartonella. Cats infected with B. henselae develop a small papule at the site of inoculation, and transient fever and lymphadenopathy.21–24 Transient neurologic signs (such as staring and behavioral abnormalities) and reproductive disorders can also occur. Some cats infected with B. henselae and/or B. clarridgeiae show no clinical signs, and gross lesions are lacking at necropsy. However, histopathology reveals peripheral lymph node hyperplasia, splenic follicular hyperplasia, lymphocytic cholangitis/pericholangitis, lymphocytic hepatitis, lymphoplasmacytic myocarditis, and/or interstitial lymphocytic nephritis.21,23 In naturally infected cats, Bartonella can rarely cause endocarditis and myocarditis. Generally speaking, infective endocarditis is rare in cats, but a few of the reported cases have been associated with Bartonella infection. B. henselae DNA has been amplified from aortic valvular vegetative lesions of cats, with visualization of the organism in lesions using silver stains.25,26 Dramatic pyogranulomatous myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis were associated with B. henselae infection in two cats that died in a North Carolina shelter, and organisms were detected in lesions with silver stains and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure 52-1).27 Carpal and metacarpal osteomyelitis was also associated with a B. v. berkhoffii infection in a cat; Bartonella DNA was detected in bone lesions as well as in the blood.28 The DNA of B. v. berkhoffii and B. henselae was also detected in cardiac tissues of several cats with systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis.29 FIGURE 52-1 A, Granulomatous myocarditis associated with Bartonella henselae infection in an 8-week-old female domestic shorthair introduced to a shelter that was ridden with fleas. B, Histopathology of the heart of the affected cat showing intralesional agyrophilic bacteria (arrows). Warthin-Starry stain. C, Short bacilli (arrows) in an inflammatory focus are immunoreactive (brown) for Bartonella henselae–specific monoclonal antibody. Immunohistochemistry with diaminobenzidine chromogen, hematoxylin counterstain. (A, Courtesy Drs. Jack Broadhurst and Edward Breitschwerdt. From Varanat M, Broadhurst J, Linder KE, et al. Identification of Bartonella henselae in 2 cats with pyogranulomatous myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis. Vet Pathol 2012;49:608-611.) Bartonella has been investigated for its role in a large number of idiopathic conditions in cats (see Table 52-3).26–38 These include uveitis,30–32 caudal gingivostomatitis,32–37 fever of unknown origin,38 lower urinary tract disease,32,36,39 chronic kidney disease,32,36 pancreatitis,40 lymphadenopathy (Figure 52-2),37 neurologic disease,32,41,42 pododermatitis,43 and chronic idiopathic rhinosinusitis.44 There is currently no convincing and repeatable scientific evidence that Bartonella infection causes any of these conditions. Studies have varied in the methodology used to detect infection (serology, culture, and/or PCR assays), and many of the conditions investigated likely have multifactorial etiologies. An understanding of the significance of Bartonella in these conditions will probably require prospective study of large numbers of cats with clearly defined clinical illness using Bartonella culture and/or PCR assays. FIGURE 52-2 Lymph node of a 1-year-old, retrovirus-negative, flea-ridden cat with a 3-month history of fever, mild lethargy, and generalized peripheral lymphadenopathy but a normal appetite. The right axillary and both mandibular lymph nodes measured 3 cm in diameter; the remaining peripheral lymph nodes were 2 cm in diameter. A serum chemistry profile revealed hyperglobulinemia (6.5 g/dL). Serum protein electrophoresis revealed a polyclonal gammopathy. Histopathology of the right axillary, right mandibular and right popliteal lymph node showed lymphofollicular hyperplasia and marked neutrophilic, lymphocytic, and histiocytic capsulitis and perilymphadenitis. Note the florid capsulitis to the right of the arrows, which indicate the outer extent of the lymph node parenchyma. Silver stains (Warthin-Starry and Steiner stains) showed a small amount of granular staining within cells, which possibly represented intracellular agyrophilic bacteria. The DNA of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae was detected in the lymph node using PCR, and blood cultures were positive for B. henselae. Interestingly, the cat was seronegative to B. henselae and B. clarridgeiae. Bartonella spp. are important causes of blood-culture–negative endocarditis in dogs (see Box 52-1).25,29,45–60 Infection with Bartonella was identified in 6 (19%) of 31 dogs with culture–negative endocarditis in California.61 Worldwide, the DNA of several Bartonella species has been detected in the heart valves of dogs with endocarditis. The most common species identified has been B. v. berkhoffii. In dogs, Bartonella endocarditis usually involves the aortic valve, although the mitral valve is occasionally affected, so the possibility of bartonellosis should not be ruled out in dogs with mitral valve endocarditis. Dogs with Bartonella endocarditis are more likely to be afebrile and more likely to have congestive heart failure than dogs with other causes of endocarditis, and their median survival time is shorter (Figure 52-3).61 Complications of Bartonella endocarditis include thromboembolic disease and neutrophilic polyarthritis. FIGURE 52-3 Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing survival of dogs with Bartonella infectious endocarditis (IE) with that of dogs with IE caused by other pathogens. (From Sykes JE, Kittleson MD, Pesavento PA, et al. Evaluation of the relationship between causative organisms and clinical characteristics of infective endocarditis in dogs: 71 cases (1992-2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006;228:1723-1734.) Bartonella, or Bartonella DNA, has been detected in lesions from dogs with a variety of chronic pyogranulomatous or granulomatous inflammatory and vasculoproliferative diseases (see Box 52-1). Bartonella was detected in a dog with peliosis hepatis and a dog with bacillary angiomatosis, rare conditions that are strongly associated with Bartonella infection in humans.54,60 Peliosis hepatis and bacillary angiomatosis are vasculoproliferative diseases characterized by the presence of blood-filled proliferations of vascular tissue in the liver and skin, respectively. Based on case reports and seroprevalence studies, Bartonella is suspected to cause polyarthritis, epistaxis, thrombocytopenia, and/or splenomegaly in dogs.17 However, these associations could also reflect the presence of other detected or undetected, co-transmitted vector-borne pathogens that cause these disorders. Bartonella has been investigated for its role in canine lymphoma62; neurologic disease63; splenic disorders including lymphoid nodular hyperplasia, hemangiosarcoma, and fibrohistiocytic nodules64; idiopathic cavitary effusion65; and idiopathic rhinitis.66 As for cats, the role that Bartonella plays in these conditions, if any, is unclear and requires further study.

Bartonellosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

Bartonella Species

Primary Reservoir

Primary Vector

B. henselae

Cats

Cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis)

B. clarridgeiae

Cats

Cat flea

B. koehlerae

Probably cats

Cat flea

B. quintana

Human

Human body louse (Pediculus humanus)

B. bovis

Ruminants (cattle, deer)

Biting flies?

B. vinsonii subspecies berkhoffii

Coyotes, domestic dogs

Unknown (fleas, ticks?)

Bartonella Species

Primary Reservoir

Primary Vector

B. henselae

Domestic cats

Cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis)

B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii

Coyotes, domestic dogs, foxes

Unknown (fleas, ticks?)

B. rochalimae

Wild carnivores, domestic dogs

Fleas (Pulex irritans)

B. clarridgeiae

Domestic cats

Cat flea

B. koehlerae

Domestic cats

Unknown

B. quintana

Human

Body louse (Pediculus humanus) (in humans)

B. washoensis

California ground squirrel

Unknown

B. bovis

Ruminants (cattle, deer)

Unknown

B. elizabethae

Rats

Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis)

B. grahamii

Wild mice

Rodent fleas (Ctenophthalmus nobilis)

B. taylorii

Wild mice

Rodent fleas (Ctenophthalmus nobilis)

B. vinsonii subsp. arupensis

White-footed mouse

Unknown

B. volans–like

Southern flying squirrel

Unknown

“Candidatus B. merieuxii” (strain HMD)

Dogs, jackals

Unknown

Epidemiology of Bartonella in Cats

Epidemiology of Bartonella in Dogs

Clinical Features

Clinical Manifestations in Cats

Clinical Manifestations in Dogs

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree