6 Bacterial diseases

There are some very serious bacterial skin diseases that are either potentially zoonotic (including multi-resistant/methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Yasuda et al 2000, Cuny et al 2006) and Burkholderia (Pseudomonas/Malleomyces) mallei) or are life-threatening to the horse. An example of life-threatening bacterial disease is the anaerobic clostridial infections that affect horses in several different ways. Tetanus can develop from deep infection with C. tetani even in an apparently trivial skin or foot injury and several gas-forming clostridial species can cause massive necrotizing damage to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Of course these diseases also illustrate the point that the specific circumstances of a wound may dictate the species of bacteria that can survive therein. Clostridia require anaerobic conditions and some other species require either acidic or alkaline environments.

In order to treat many of the bacterial skin diseases (whether primary or secondary) it is important to know the species involved and where possible its antibiotic sensitivity profile. There are few antibiotics that are available for horses and so careful/rational use is essential. Diagnostic bacteriology may be helpful but it can also be misleading – the underlying primary disease can be immunological, for example, and the detection of potentially pathogenic bacteria on the diseased skin may not be the most important aspect of the disease. Diagnostic investigations for bacterial disease are well established but it is important that a truly representative culture is achieved and therefore a presumptive diagnosis should be made and the sampling adjusted to take account of where the bacteria might best be identified. Deep swabbing from the site of a biopsy or culture of a whole biopsy specimen may be indicated. There may be some wish to surgically prepare the site before biopsy or swabbing but this will clearly have a very significant effect on the outcome of any attempt to culture the whole spectrum of bacteria involved (see p. 64).

1. The delivery of the drug to the site of infection is not effective either because the drug is not administered appropriately or because the site precludes delivery.

2. The drug is wrong for the bacterial species concerned or the wrong dose or route is being used.

3. There has been a change in the bacterial species or the sensitivity of the cultured organism.

Abscess

Profile

The infecting organism usually gains access through skin wounds but can be disseminated into the skin through the blood and/or the lymphatic system or as extensions from infected foci in adjacent subdermal tissues. Ectoparasites may be responsible for transmission of infection into the skin, for example in some cutaneous abscesses such as those due to Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis in the pectoral and chest regions and widespread small abscesses due to Histoplasma farciminosum (epizootic lymphangitis) (Welsh 1990).

1. Cutaneous and subcutaneous abscesses are a regular clinical presentation. The foot is the most common anatomic site.Sterile abscesses also occur. Some remain localized, others are less defined.

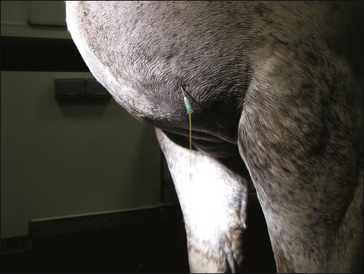

2. Focal or diffuse swelling with signs of inflammation. Size varies. Single and multiple abscesses are encountered.Characteristic early painful focus that becomes softer and then bursts with purulent discharge. Purulent discharges tend to cause skin inflammation below the abscess site.

3. Diagnosis is based on clinical examination and ultrasound examination. Aspiration can help to confirm the diagnosis and the infective organism.

4. Treatment involves establishing drainage of the abscess site.Antibiotics may be appropriate in some sites and the tetanus status of the animal should always be considered.

5. In most cutaneous sites the prognosis is good but this may be varied when the underlying cause is difficult to resolve. Multiple abscesses can occur and when they are at different stages of development different approaches may need to be taken.

Clinical signs

There is a characteristic progression from a hard, painful nodule surrounded by an area of acute inflammation with heat and swelling (Fig. 6.1) to a softer texture with skin thinning in one site (usually). The fluid may fluctuate on palpation in the later stages.

The overlying skin becomes thinner and eventually bursts. The accumulated debris/pus is usually fluid in consistency at the stage of bursting and if in a suitable site it may drain under gravity. In some cases there is no fluid pus and the site is made up of necrotic tissue that is far more difficult to remove.

Purulent discharges can cause significant skin damage (Fig. 6.2).

Multiple interlinking cutaneous abscessation involving relatively small individual abscesses is a feature of epizootic lymphangitis (see Fig. 7.20), glanders (see p. 161), sporotrichosis (see p. 178) and ulcerative lymphangitis (see p. 155) amongst some other conditions. The causative organisms and the epidemiological situation may help to establish the cause and the likely outcome.

Clostridial abscess is characteristically associated with gas formation and has a less localized character. Pain and local swelling are often severe and there may be extensive sloughing of the skin and underlying necrotic muscle, etc. (Fig. 6.3). The affected horse is invariably very ill until the infection is controlled.

Differential diagnosis

• Haematoma: these are soft and fluctuant from the outset and usually not painful apart from any primary injury that results in haematoma formation; the fluid nature is easy to appreciate.

• Cyst: usually not painful, inflamed or progressive, but some dermoid cysts can become secondarily infected and/or inflamed and then may develop into an abscess.

• Acute eosinophilic granuloma: solid, mildly painful and not usually progressive; they seldom soften and usually subside spontaneously.

• Hernia: the contents can be identified and most are reducible.

• Nodular neoplastic lesions, e.g. sarcoid/lymphosarcoma: tumours are usually well defined or have typical characteristics; some faster growing ones with necrotic centres and those with ulcerated surfaces can abscessate; tumours often have impaired local immunity and so secondary infections are common.

Treatment

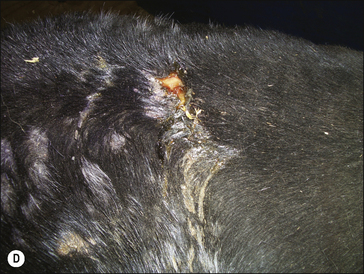

Following the development of an abscess, the surrounding skin may lose its hair and the superficial epidermis and the hair may slough off. This is possibly due simply to pressure and sustained local inflammation. These changes are invariably temporary but the site of the abscess may show a detectable scar (Fig. 6.4).

Purpura haemorrhagica (see p. 275) can be a sequel to prolonged abscessation (particularly that due to Streptococcus equi equi, S. equi zooepidemicus) whether or not the abscesses are satisfactorily treated and/or drained.

• The purulent discharge from most abscesses is laden with bacteria and this can be a significant source of infection for other animals and, indeed, other sites of injury on the affected horse.

• Horses suspected of having either strangles or Wyoming strangles should be isolated before and after abscesses are surgically drained. Discharging abscesses also attract flies (both surface feeders and myiasis species).

• The discharges and swabs, instruments etc., from the serious diseases such as strangles (Streptococcus equi), epizootic lymphangitis (Histoplasma farciminosum), glanders (Burkholderia (Pseudomonas/Malleomyces) mallei), sporotrichosis (Sporothrix schenckii) and Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis must be effectively disinfected.

Cheek abscess

Profile

1. A specific entity affecting the cheeks as a result of either abrasion or penetrating foreign bodies from outside or within the mouth. Usually streptococcal organisms such S. equi var.zooepidemicus are involved.

2. Multiple, painful focal abscessation with small discharging sinus tracts and a generalized local painful swelling (suggestive of cellulitis) is presented. Abscessation seldom develops into a single focal mass and is more often a series of smaller linked tracts.

3. Diagnosis is based on clinical grounds and on culture from the discharging purulent material.

4. Treatment with antibiotics and irrigation is indicated.Antibiotic selection will depend on culture results. Most are streptococcal, however, and penicillin is usually a reasonable first choice approach. The cause must be addressed if it can be identified

5. The prognosis is good but some local deformity, alopecia and loss of pigmentation may occur.

Clinical signs

Acute, painful, hot swelling of the commissure of the mouth or adjacent cheek area is typically encountered. Multiple small interlinking sinus tracts with small areas of exudation over pointing abscess can be seen (Fig. 6.5).

Differential diagnosis

• Bit injury in the mouth: usually this is focal and has an obvious cause.

• Buccal laceration from teeth inside the commissure: multiple buccal and possibly lingual ulceration usually present.

• Foreign bodies: these are difficult to identify.

• Tumours (ulcerated melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma or sarcoid in particular): usually these are firmer and better defined and are seldom patently infected.

Diagnostic confirmation

• Cuts or wounds inside the mouth adjacent to the abscess.

• Typical clinical features of heat, pain and swelling with an interconnected multifocal inflammatory nature.

• Culture of discharges and swabs taken from within the lesions usually identify Streptococcus spp. bacteria.

• Ultrasonography can help to differentiate this from tumours and other inflammatory and non-inflammatory disorders.

Bacterial folliculitis and furunculosis (acne/superficial pyoderma)

Profile

Folliculitis is inflammation of the hair follicle with accumulation of inflammatory cells within the follicle lumen. Most commonly it is caused by bacteria involving coagulase-positive Staphylococcus spp. (S. aureus, S. intermedius and S. hyicus) (Chiers et al 2003) and Streptococcus species are isolated. Multi-(methicillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has recently been identified from healthy horses (Yasuda et al 2000) and whilst the significance of this to horses has yet to be established it is becoming more of a concern to veterinarians.

Key points: Bacterial folliculitis and furunculosis

Key points: Bacterial folliculitis and furunculosis

1. A relatively common occurrence – often with Staphylococcus spp. or Streptococcus spp. bacteria. Most cases appear to relate to hygiene or cutaneous immunity problems. Exposed, hairless (glabrous) skin surfaces are most often involved, e.g.the sheath/groin and the sides of the face, but the saddle region and body skin can be seriously infected.

2. A painful localized region in which papules can be ‘ felt ’ in the skin that develops into an inflamed, exudative and oedematous area is typical; these lesions are often circular and exudative in the early stages. Some develop into isolated individual pustules while others coalesce into abscesses or furunculosis.

3. Diagnosis is usually simple but the changes are not pathognomonic for any particular bacterial species; early lesions can easily be confused with various forms of dermatophytosis.Pain usually indicates Staphylococcus spp. bacteria but other species may be involved.

4. Treatment is sometimes problematic and recurrences are common. Local warm washes with antiseptic shampoos such as chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine, systemic antibiotics and oral potassium iodide are all helpful. Skin and stable hygiene are important. Treatment courses of several months may be required.

5. The prognosis is fair but some cases take a long time to resolve and the healing lesions are sometimes alopecic and/ or have permanently altered hair colour and quality.

As the infective process proceeds, degeneration of the hair follicle leads to infection of the surrounding dermis and subcutis. This is called furunculosis. The condition is usually related to areas of rubbing due to dirty or ill-fitting harness, rugs or saddle cloths. Most cases occur in late spring or early summer coincidental with hair shedding, humidity and increasing work with dirty or poorly maintained tack. Poorly groomed horses have a higher tendency to develop the condition. Horses in poor condition, or immunocompromised animals or those on medications likely to be immunosuppressive also seem more likely to be affected (Inokuma et al 2003).

Dermatophilus congolensis is a common cause of bacterial dermatitis and folliculitis and is considered in its own right (see p. 156). More rarely Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is responsible and this too is considered in its own section (see p. 155). Fungi including dermatophytosis and cutaneous mycetoma/fungal granuloma can also be involved (see p. 183).

Clinical signs

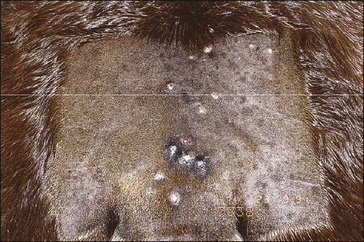

Usually a rapid development of small (2–5 mm diameter), painful papules is reported – in the early stages these may be more easily felt than seen unless the hair is closely clipped (Fig. 6.6). The first sign may be the presence of roughly circular areas (2–6 cm diameter) of erect hairs with a small matted crust around the base.

Palpation is usually resented and pain is usually marked. The papules develop an ulcerated central area with extensive local oedema and exudation (Fig. 6.7).

Where multiple infections coalesce locally, it becomes a carbuncle or boil; these occur in horses with saddle rash/scab (Staphylococcus aureus, S. intermedius), heat rash, cheek abscess (see Fig. 6.5) and ‘pigeon-breast’ (Wyoming strangles due to Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis).

There may be evidence of enlarged cutaneous veins and lymphatics leading from the affected sites (Fig. 6.8).

There is seldom pruritus and in uncomplicated cases there are no systemic signs of illness.

Some superficial lesions fail to heal and these may become deeply infected (furunculosis) with sinus tracts and discharging sinuses. Chronic granulation tissue diffusely infiltrated with microabscesses and sinus tracts is often classified as botryomycosis (pseudomycetoma) on the skin (see Fig. 6.10), or as scirrhous cord at the site of non-healing castration wounds (Fig. CD6 • 4A and B)  .

.

A staphylococcal infection of the palmar/plantar pastern region (see p. 153)is a recognized entity in the pastern dermatitis complex (see p. 471). Although this condition is caused by the same group of bacteria it is a recognizably different syndrome – usually poor hygiene is not the main instigation but skin maceration due to continued wetting and a primary superficial infection may be involved.

Differential diagnosis

• Dermatophilosis: this can be difficult to differentiate without bacteriological cultures and skin biopsies but it usually affects the dorsum of the back and the lower limb regions.

• Other bacterial pyoderma (e.g. Streptococcus equi equi– strangles).

• Fungal folliculitis: these are usually much more long-standing, slower progressing and isolated and are seldom painful; fungal organisms can be identified in skin biopsies.

• Dermatophytosis: this seldom shows significant pain and exudate but secondarily infected dermatophytosis lesions can be similar; the fungal organisms can be identified in skin scrapings and hair plucks.

• Onchocerciasis: this condition induces a more diffuse change in most cases and is seasonal and regionally restricted; the microfilariae or adult parasites can usually be identified directly or in biopsies; these lesions can be secondarily infected as well.

• Generalized granulomatous disease (enteritis/sarcoidosis) multi-organ involvement.

• Pemphigus foliaceus: generalized focal or diffuse junctional exfoliative disorder.

• Greasy heel syndrome: complex of conditions resulting in a chronic verrucose thickening of the pastern with pseudo-tumour formation and granulation, infection and ulceration.

Diagnostic confirmation

• Clinical features and pain are usually characteristic but mixed infections are common.

• Biopsy is usually avoided if possible but a fine biopsy punch (3 mm) may be useful, particularly for culture.

• Bacteriological culture and sensitivity are important but deep biopsy may be needed for significant culture (Fig.CD6 • 5A and B)  .

.

Treatment

Three aspects must be considered during the management of a case of pyoderma. These are:

1. Control of the specific lesions on the affected horse. The affected areas should be clipped and washed with warm water and an antiseptic such as chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine surgical scrub solution. This should be left on the skin for some 5–10 minutes before being rinsed off thoroughly, again with warm water. Washes are useful also for controlling the spread of the organisms responsible (Fig. CD6 • 5C and D)  .

.

Parenteral antibiotics are useful adjunctive therapy. Culture and sensitivity testing should always dictate the selection but the most common antibacterial used is potentiated sulphonamide because it is usefully effective and can be maintained for weeks if necessary by oral dosing for up to 2 weeks (White 1988).

Many isolates are resistant to parenteral penicillin but where they are shown to be sensitive this can be useful, at least initially. Enrofloxacine can be effective also but should not be used in horses under 2 years of age. Although vancomycin and other potent drugs in that class would probably be effective (Orsini et al 2005), their use represents irresponsible antibiotic use except in absolutely exceptional circumstances.

1. Topical dressing with silver sulfadiazine or where feasible silver wound dressings should always be considered. Modern adhesive dressings such as adhesive hydrocolloid (DuoDerm, Convatec, UK) are very useful, even on the body trunk, and can be combined with hydrofibre silver dressings (Aquacel Ag, Convatec, UK) to provide an excellent local antibacterial effect.

2. Prevention of further outbreaks on the affected animal. This usually involves significant improvements in the overall hygiene and the health status of the horse. However, even in the best management systems with the healthiest horses, recurrences are to be expected. Turning out into sunshine (but avoidance of wetting by rain) is helpful and where this cannot be done, ultraviolet and infrared lamps can be helpful. Continued washing is to be avoided as far as possible but may be unavoidable. Recurrences are nevertheless common.

3. Control of the environmental contamination and prevention of spread to other horses in contact. All tack and rug contact with the affected skin should be prevented. Washing and sterilizing of all tack, grooming equipment, rugs, etc. is strongly advised Tertiary amine disinfectants have strong antibacterial properties without much risk of damage to tack or other equipment. Fumigation of all tack with formaldehyde gas is often the best approach to sterilization of the equipment but is more difficult (see p. 86).

Bacterial granuloma (botryomycosis/staphylococcal pseudomycetoma/deep pyoderma)

Clinical signs

A slow or non-healing wound with induration of the wound margins (Fig. 6.9) is typical. A chronic purulent discharge from one or more sinuses within the wound site is common.

Exuberant granulation tissue forming rosettes of complex granulation tissue and multiple microabscesses with sinuses may develop (hence the derivation botryo– meaning grape-like) (Fig. 6.10). Small yellow-white granules/grains may be visible in the purulent discharge. Tracking along lymphatic vessels sometimes occurs. It can reach large (or even enormous) proportions. The condition is seldom painful or pruritic. Affected horses do not often show systemic illness, but very large lesions can be debilitating.

Key points: Bacterial granuloma

Key points: Bacterial granuloma

1. This is a bacterial infection usually involving staphylococcalmicroabscessation. The concurrent chronic inflammation and (unhealthy) granulation tissue combine to produce exuberant masses. A specific form of this condition occurs as a non-healing, fistulated, discharging castration site when the enlarging mass forms at the end of the spermatic cord (a socalled champignon or mushroom).

2. Clinically relatively easy to recognize but bacterial causes canvary.

3. Biopsy is usually simple because the tissue has no bloodsupply – swabs should be taken from the base of the biopsysite rather than from the lesion surface.

4. Treatment involves removal of all infected tissue and restoration of the wound site to a surgical wound. Silver dressings are helpful in controlling the infection. Prolonged antibiotics are required. Oral potassium iodide is also helpful. (Note: Potassium or sodium iodide should not be given to pregnantmares under any circumstances.)

5. The prognosis depends on the feasibility and efficiency of removal of the infected tissues and then the degree to which repeated infection can be controlled. Many cases require more than one surgical procedure.

In a few cases the infection may become much more extensive, especially if the animal is immunocompromised in some way. Where this occurs the infection may extend to the local lymph node where gross enlargement can occur. This form is commonest in ponies with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (equine Cushing’s disease) and the introduction of the infection usually requires some skin damage such as pruritus from insect bite hypersensitivity (Fig. 6.11). An accurate history of the horse and a thorough clinical examination are essential aspects of the case investigation.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Key points: Abscess

Key points: Abscess

.

. .

.

Key points: Cheek abscess

Key points: Cheek abscess

.

.

.

.