CHAPTER 105 Assessing Saddle Fit in Performance Horses

Back pain is a common problem in athletic horses and is associated with signs that range from mild discomfort to pain severe enough to incite dangerous behavior. This chapter addresses the role of saddle fit in the equine back pain conundrum.

STRUCTURE AND FIT OF THE SADDLE

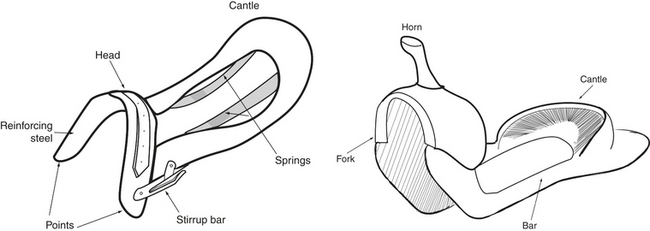

Most saddles are built on a tree (Figure 105-1) that provides rigidity and gives attachment to the leather exterior, although treeless saddles are available. The tree determines the fit of the saddle and affects the weight distribution on the horse’s back. A broken tree fails to distribute the pressure evenly over the horse’s back and may concentrate pressure in small areas. The tree may also become twisted, most often as a result of the rider always mounting on the same side, which gives the saddle an asymmetric appearance and results in pressure being concentrated on one side or in focal areas on the horse’s back. A twisted tree cannot be straightened.

The tree of an English saddle may be rigid (non–spring tree) or somewhat flexible (spring tree). The arch supports the pommel, the points extend downward from the arch to stabilize the front of the saddle across the withers, the bars support the stirrup leathers, and the cantle underlies the seat (see Figure 105-1). Some saddle makers recess the bars inward to enhance the rider’s comfort but, if recessed too far, they can pinch the horse’s back muscles in the area behind the withers. The panels, which are the weight-bearing part of an English saddle, separate the rigid tree from the soft and deformable back muscles. They should be long and broad to spread the weight over a large area, with their slope matching the curvature of the horse’s back in both craniocaudal and mediolateral directions (Figure 105-2).

The panels are flocked (stuffed) with shock-absorbing material, such as wool, synthetic fleece, foam, horsehair, or air. There should be sufficient flocking to give a firm, resilient feel without any lumps. Insufficiently flocked panels may not conform to the shape of the horse’s back or absorb energy. Overflocking produces hard, bulging panels with small contact areas on the horse’s back. It is usually necessary to have the flocking adjusted within the first year of use and periodically thereafter. In an English saddle, the girth attaches to the billet straps, which vary in number and direction of attachment to allow flexibility in saddle placement.

The tree of a western saddle is larger and constructed somewhat differently from that of an English saddle (see Figure 105-1). The forks form an arch at the front of the saddle to which the horn is attached. The bars, which are the main weight-bearing area, run the length of the saddle on each side and are joined at the cantle. The underside of the saddle is lined with sheepskin, through which the size and shape of the tree can be felt. Because the sheepskin does not offer much cushioning beneath the bars, western saddles are intended to be used with a thick (2 to 2.5 cm) pad to protect the horse’s back. The rigging is an arrangement of rings and plates that anchor the straps used to hold a western saddle in place. Several styles of rigging are available.

The gullet is a channel between the left and right weight-bearing surfaces of the saddle that overlies the spinous processes (see Figure 105-2). It should be sufficiently wide throughout its length (7 to 8 cm) for the vertebral column to move from side to side within the channel when the horse’s back bends laterally and high enough to clear the withers when the rider is sitting in the saddle. In horses with long withers that extend far caudally, the fit should be checked to ensure that there is no gullet pressure against the back of the withers, which cannot be determined from in front of the pommel.