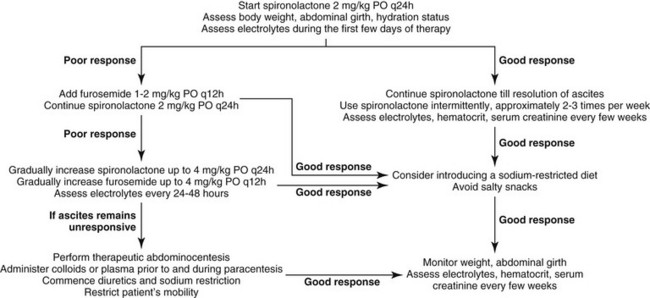

Chapter 144 Despite PH, ascitic animals actually have systemic hypotension and increased renal sodium retention because of reduced glomerular filtration rate and increased activation of the RAAS. Activation of the RAAS results in the release of aldosterone and increased sodium retention in the distal renal tubules. The aldosterone antagonist spironolactone is the diuretic of choice for the treatment of hepatogenic ascites. Spironolactone competes with aldosterone for its intracellular receptor sites, thus promoting sodium excretion and potassium retention in the renal tubules. Therapy with spironolactone at a dose of 2 mg/kg q24h PO is the initial therapy for animals with ascites resulting from PH (Figure 144-1). The dose of spironolactone can be increased gradually every few days to a maximum of 4 mg/kg q24h PO. Some animals may benefit from twice-daily therapy. Spironolactone can have a relatively slow onset of activity in humans, taking up to 14 days to cause diuresis; this also may occur in cats and dogs. In cases that are refractory to spironolactone, or when a more rapid resolution of ascites is required, furosemide (1 to 2 mg/kg q12h PO) also can be used. If there is no response to this dose of furosemide, it can be increased incrementally. Therapy with furosemide rather than spironolactone has been shown to precipitate more complications in humans with ascites, however. Importantly, serum electrolyte concentrations, especially sodium and potassium, should be monitored daily during the first few days of diuretic therapy, and every few weeks to months thereafter. Hypokalemia should be addressed as soon as possible as it can precipitate hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (see later). Body weight, abdominal girth (measure girth at level of the second lumbar vertebra with a tape measure), and hydration status as well as hematocrit and serum creatinine also should be monitored when on diuretic therapy. A safe loss of 0.5% to 1.0% body weight per day has been suggested for humans. Body weight reductions of 5% per day are dangerous and indicate the need for veterinary examination. When ascites has been mobilized adequately, intermittent use of diuretics is advised and guided by fluid reaccumulation. Administration of a diuretic two or three times per week is often sufficient to control fluid accumulation.

Ascites and Hepatic Encephalopathy Therapy for Liver Disease

Ascites

Therapy for Ascites

Diuretics

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ascites and Hepatic Encephalopathy Therapy for Liver Disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue