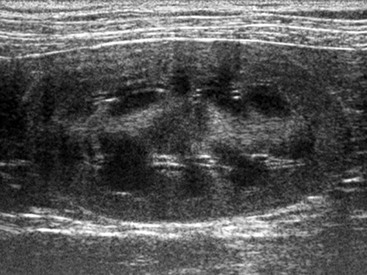

Chapter 185 Normal kidneys have an ovoid shape and are smoothly marginated. Generally, the size of the left and right kidney in the same animal should be similar. Because of the large variability in size between dogs of different breeds renal size traditionally has been evaluated with radiography rather than ultrasound. A normal range of 5.5 to 9.1 for kidney : aorta ratio has been proposed recently that allows objective assessment of renal size in a given dog. In cats, renal size is more consistent and should be approximately 3.0 to 4.5 cm in length. The renal cortex is hyperechoic to the strongly hypoechoic centrally located medulla (Figure 185-1), hypoechoic to the spleen, and isoechoic to hypoechoic to hepatic parenchyma. Many factors affect the echogenicity of the renal cortex, including normal variation, renal fat deposition, and transducer frequency so care must be taken not to overinterpret a mild generalized increase in renal cortical echogenicity as a pathologic change. The medulla is hypoechoic, and interlobar and arcuate vessels can be followed as anechoic tubular structures with hyperechoic walls crossing the renal medulla and branching at the level of the corticomedullary junction, respectively. When the kidney is investigated with color Doppler ultrasonography additional smaller branches (interlobular vessels) may be seen in the renal cortex. The renal pelvis may or may not be visible and should measure less than 2 mm wide in normal dogs and cats. Normal ureters usually are not visualized. Figure 185-1 Sagittal ultrasonographic image of the normal left kidney in a cat. The medulla is hypoechoic compared with the surrounding cortex and the centrally located peripelvic fat.

Applications of Ultrasound in Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Disease

Normal Findings

Applications of Ultrasound in Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree