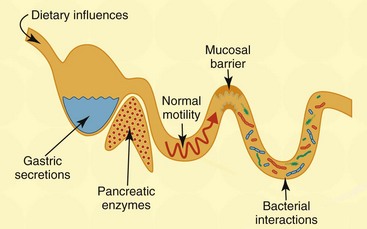

Chapter 126 Antibiotic-responsive enteropathy (ARE) denotes a clinical syndrome characterized by acute or chronic diarrhea in animals that responds to antibiotic treatment (Hall, 2011). Well-recognized gastrointestinal (GI) disorders broadly responsive to antibiotics may be found in Box 126-1. Previously, this clinical disorder was termed idiopathic small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which implied that an absolute increase in bacterial numbers of the small intestine was responsible for disease pathogenesis. The term ARE is more appropriate than SIBO, given the unreliable nature of culture-dependent assays in quantifying intestinal bacterial numbers and the misunderstanding of what constitutes normal versus abnormal microbial densities and composition mediating GI disease. The GI tract in dogs and cats is colonized with a vast microbiota that is estimated to range between 1012 to 1014 organisms from 10 to 12 different bacterial phyla (Suchodolski, 2011). These bacteria play a crucial role in immune system development and help to maintain gut health through regulatory signals delivered to the epithelium that mediate mucosal homeostasis. Major functions of the intestinal microbiota affecting GI health include metabolic activities that cultivate energy and nutrients (e.g., short-chain fatty acids [SCFA], folate, and vitamin K), the trophic effects on intestinal epithelia and immune structure/function (i.e., bacterial-induced host gene expression and regulation of T-cell repertoires), and protection against invasion by pathogenic microbes via the production of antimicrobial substances, such as bacteriocins. Fecal bacterial culture useful for identifying a specific enteric pathogen (e.g., Campylobacter jejuni) has given way to culture-independent molecular techniques for in-depth analysis of complex bacterial communities. Contemporary studies using molecular microbiology have determined that the majority (>70%) of the GI microbiota is uncultivable, and composition and total bacterial numbers in different GI segments and luminal contents differ considerably as compared with the mucosa. It now is realized that the composition of gut flora in healthy dogs and cats is distinctly different. Healthy cats were shown to have a large number of total and anaerobic bacteria in the small intestines, which appear to be stable before and after antibiotic (metronidazole) administration (Johnston et al, 2000). A separate investigation similarly found high (104 to 108 CFU/ml) numbers of obligate anaerobes in the duodenum of cats but showed no differences in bacterial composition between healthy cats and cats with signs of GI disease (Johnston et al, 2001). Several different pathogenic mechanisms may contribute to the development of ARE. Aberrant host-microbial interactions have been associated with enteropathogenic bacterial infection, quantitative increases in total microbial numbers (SIBO), imbalances in enteric microbial composition (i.e., dysbiosis), and/or secondary to defects in mucosal barrier integrity (Hall, 2011). Colonization of the GI tract by pathogenic bacteria (i.e., infectious diarrhea) may induce gastroenteritis by direct mucosal invasion (e.g., invasive Salmonella spp.) or the secretion of enterotoxins, which are directly injurious to intestinal epithelia (e.g., Clostridium difficile) or which stimulate the secretion of fluid and electrolytes (Clostridium perfringens), causing secretory diarrhea. Still other bacteria may produce diarrhea in dogs and cats through bacterial attachment to the intestinal epithelial surfaces (i.e., enteroadherent streptococci). Adherent and invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) now are associated with the development of granulomatous colitis in susceptible boxer dogs (Simpson et al, 2006). Canine SIBO traditionally is defined on the basis of increased numbers of total bacteria in duodenal juice, but controversy exists as to what bacterial quantity constitutes normal. Under physiologic conditions, the bacterial population of the small intestine is controlled by several host mechanisms (Figure 126-1). Although the numeric limits of bacteria found within asymptomatic dogs may vary by breed and within individuals of the same breed, there is general consensus that SIBO may occur secondary to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, impaired clearance of bacteria (e.g., intestinal obstruction, motility disorder), and morphologic injury to the mucosa (e.g., infiltrative mucosal disease). Increased numbers of intestinal bacteria (i.e., SIBO) may cause malabsorption and diarrhea through (1) competition for nutrients (the bacterial binding of cobalamin, which impairs its intestinal absorption); (2) bacterial metabolism of nutrients into secretory products (e.g., hydroxylated fatty acids, deconjugated bile salts) that promote colonic secretions; and (3) biochemical injury to the intestinal brush border, which decreases enzyme activity causing maldigestion (Hall, 2011). Figure 126-1 Host mechanisms contributing to microbial homeostasis. A variety of factors may affect the numbers and diversity of the gastrointestinal microbiota, including environmental factors (diet), host factors (gastric acid secretion, pancreatic digestive proteases, normal intestinal peristalsis, functional innate immunity, secretory immunoglobulins), and bacterial factors (immune modulation, competition for substrate and binding sites, interaction [“crosstalk”] with enterocytes, production of antibacterial substances).

Current Veterinary Therapy

Antibiotic Responsive Enteropathy

Host-Microbiota Interactions in Healthy Animals

Pathogenic Mechanisms

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree