Chapter 5 Parrots and related species

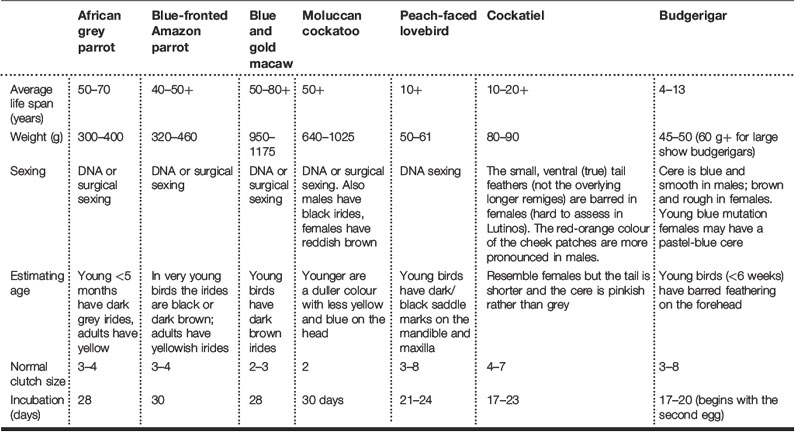

Members of the parrot family are the commonest avian pet and, therefore, the most likely to be presented to the veterinarian. Table 5.1 shows the most commonly encountered species.

Consultation and handling

It is important to weigh parrots at every consultation (Fig. 5.1); tame birds can be accurately weighed using a small perch designed to fit on to standard weighing scales.

Important non-specific clinical signs in parrots

From Malley (1996).

Nursing care

Fluid therapy

Fluid administration

Table 5.2 Parrots and related species: Cloacal administration

| Species | Suggested volumes for cloacal administration (mL) |

|---|---|

| Budgerigar | 0.5 |

| Cockatiel | 1 |

| Amazon | 4 |

| Macaw | 6–7 |

Table 5.3 Parrots and related species: Suggested individual bolus volumes

| Species | Bolus volume (mL) |

|---|---|

| Budgerigar | 1–2 |

| Cockatiel | 2–3 |

| Conure | 4–6 |

| Amazon | 8–10 |

| Macaw | 15–25 |

Wing clipping of pet parrots

A badly clipped bird is not only at increased risk of damage to itself, but such clipping may predispose to feather picking and self-mutilation. Wing clipping can be controversial but the major justification for wing clipping is that by doing so it facilitates the necessary interaction between a pet parrot and the other family members, allowing the bird to become involved with, and behave as, part of the family (or ‘flock’) rather than it be confined to its cage. However, the ideal would be that the bird is left fully flighted and controlled verbally using commands such as ‘step up’, ‘step down’, ‘leave’ and ‘no’.

Analgesia

Table 5.4 Parrots and related species: Analgesic doses

| Analgesic | Dose |

|---|---|

| Butorphanol | 0.5–4.0 mg/kg i.m. every 2–4 h |

| Carprofen | 1.0–4.0 mg/kg s.c. p.o. b.i.d. |

| Ketoprofen | 1.0–5.0 mg/kg i.m. b.i.d. or t.i.d. |

| Meloxicam | 0.1–0.5 mg/kg s.c., p.o. s.i.d. |

| Morphine | 0.1–3.0 mg/kg i.v. |

Anaesthesia

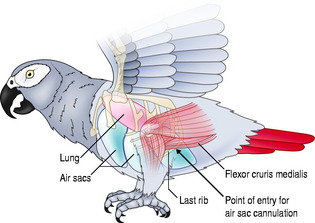

Air sac perfusion anaesthesia

Air sac perfusion anaesthesia technique

Skin disorders

Avian skin is very thin with the epidermis only up to 10 cells thick in feathered areas. There are few cutaneous glands:

Commensal bacterial numbers on the skin of birds are considered to be lower than those found on mammals. Yeasts are infrequent commensals. Malassezia not isolated from normal or self-mutilating birds (Preziosi et al 2006); in the same study, Candida albicans was isolated but significance was unclear.

Feather types

Signs of skin disease

Pruritus

Feather damage, pathology and loss

Diet

Scaling and crusting

Nodules and non-healing wounds

Chronic ulcerative dermatitis (CUD)

Neoplasia

Findings on clinical examination

Investigations

Management

Treatment/specific therapy

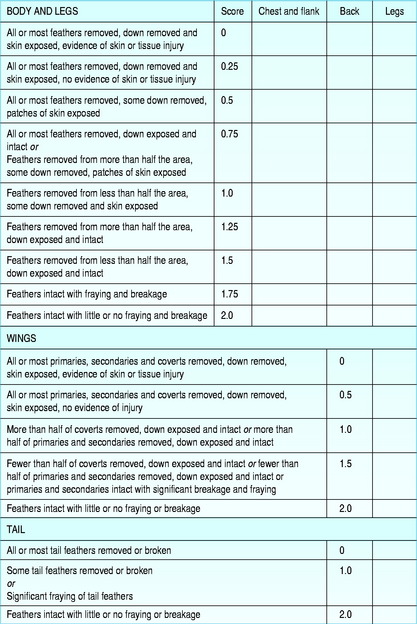

The self-mutilating parrot

Self-mutilation, like stereotypies, is a form of abnormal repetitive behaviour exhibited in captive parrots. Often psychological in origin, the alternative of an underlying causal disease should not be ruled out, either as differential diagnoses or as contributing factors. Epidemiological evidence (Garner et al 2005) points towards there being an inherited susceptibility, an increased incidence in females and a link to certain stressful environmental conditions. There are no ‘quick fixes’ and investigation is often prolonged and expensive. A methodical and holistic approach is required. This should take into account the background of the bird, its environment, its disease status and its psychological well-being.

Background

Environmental

Lighting

Diet

Environmental toxins

Findings on clinical examination

Investigations

Pathological causes of self-mutilation

Refer to Skin Disorders, above.

Otherwise significant conditions include:

Psychological causes of self-mutilation

Psychotropic drugs

Management

Upper respiratory tract disorders

Investigations

Sinusitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree